Introduction

In this essay, we present the results of an artistic research project, exploring the boundaries of animation through the exhibition of, and reflection upon, a series of collaborative artworks. We will discuss a range of animation installations that share a focus on the connection between animation, human cognition, and memory. While this connection has been studied theoretically, there exists little documentation of how it can inspire artistic practice, especially concerning experimental or expanded forms of animation. This essay, therefore, has a double goal: (1) to discuss several key theories on the cognitive foundations of animation, with special attention to processes of (de) materialization through the use of shadow and light; (2) to present a range of animated works that have been created within this framework, and reflect on how these can complement the insights of authors such as Wells (1998), Torre (2017), and Van Gageldonk et al. (2020).

Artistic research is a relatively young but fast-growing methodology that attracts an increasing number of researchers and scholars. It places artistic creation at the heart of the investigative process and as such it is akin to practical research that has a long tradition within, for instance, engineering (Coessens et al. 2009). It is, however, different from applied research in the sense that it embraces the unexpected, often intuitive nature of the artistic process, which can lead to unpredicted research outcomes (Raami 2015; Coessens et al. 2009). An essential part of artistic research is that it generates so-called tacit knowledge: knowledge that cannot be merely captured in written form but is contained within the artistic works that are created and can be understood as such by peers and fellow practitioners (Borgdorff 2010). Nonetheless, the creation of theoretical knowledge is highly relevant in artistic research: the artist-researcher uses theoretical knowledge to inform, inspire, and critically evaluate their practice, thereby becoming what Donald Schön referred to as a reflective practitioner (Schön 1983). Because of its fluid and experimental nature, artistic research is highly suitable for generating interpretive, nonlinear, and immersive insights into personal and communal discourses, complementing the results of existing qualitative and quantitative methods of inquiry (Sullivan 2009).

Following the nature of artistic research, the essay is organized into a theoretical and artistic part. In the theoretical part, we will first give a general overview of the main areas of interest in the field of animation, cognition, and memory, after which we will apply these ideas, in a second part, to the domain of expanded animation. In a third section, we will extend this line of thought to the use of light and shadow in expanded animation, drawing inspiration from diverse cross-cultural sources such as the Wayang theatre or Magic Lantern projection, and integrating a cross-temporal approach combining the principles of 19th-century optical toys such as the phenakistiscope, zoetrope, and praxinoscope with contemporary technology.

Furthermore, in the artistic part of this essay, we will describe six animated works that have been created, in order to find artistic answers to the questions of memory, preservation, and (de)materialization. Although discussed separately, these works are fundamentally interrelated, building on each other, parallel to the construction of academic knowledge through referencing, thereby bridging different areas of expertise and cultural backgrounds in an attempt to reveal what is universal rather than individual. Finally, in conclusion, we will connect these theoretical and artistic perspectives by identifying some directions for future experimental practice.

Animation and Memory

Animation has a long history of dealing with topics of cognition and memory, for instance through the use of nonlinear associative storytelling (e.g., Yuri Norstein’s Skazka Skazok/Tale of Tales), by recreating the history of certain places or cultures (e.g., Vuc Jevremovic’s Patience of the Memory) or by recounting instances of individual or collective trauma (e.g., Ülo Pikkov’s Body Memory). A comprehensive overview of the different ways in which animation can be considered as a performative practice enacting the processes of recounting and remembering can be found in the introduction of van Gageldonk et al.’s book on the subject (2020). Animation films often deal with remembering, forgetting, or dreaming, and make frequent use of visualization methods that represent these processes. Animation is particularly suitable for this, as it incorporates cinematographic techniques that are less intuitive to other media: nonlinear and fragmented time (e.g., Satoshi Kons’s Paprika), muted or fluid colors (e.g., Studio Ghibli’s The Tale of the Princess) or distortion (e.g., Richard Linklater’s Waking Life). In several respects, animation can be considered more ‘irrational’ and ‘incomplete’ than other narrative art forms, and in that sense, it is interestingly related to human cognition (Walden 2018).

Paul Wells (1998) identifies several ways in which animation is connected to memory. From a historical point of view, animation films often function as documents that capture the essence of a time or place. Psychologically, animation has the potential to evoke feelings of nostalgia and activate long-term memory in powerful ways. Related to this is the observation that animation often relies upon shared symbols that define a group or society, representing what Carl Jung refers to as its collective subconscious. As animated films are often rooted in mythology, folklore, or legends, it can even be argued that animation serves to archive and materialize these shared stories, preserving them for future generations. Finally, still according to Wells (1998), on the semantic level, the language of animation—specifically its ability to morph, transform, and visualize the intangible—makes it highly suitable to represent or mimic the processes of memory, dreams and thought: “Animation is especially suited to the process of associative linking, both as a methodology by which to create image systems, and as a mechanism by which to understand them” (Wells 1998, 94).

Elaborating on this last point, Dan Torre (2017) describes a number of additional characteristics that set animation apart from other time-based audiovisual media: it is fluid, volatile, rooted in imagination, and open to exaggeration and decontextualization. Animation is deeply connected with human cognition because it reflects, but in its turn also impacts, our ways of thinking, triggering strong mental responses. The specific techniques that animation uses to organize space and time, according to Torre, can be linked to how our mind stores, processes, and retrieves information: “many of the processes of animation and, in fact, the very concept of animation is a basic and natural extension of our real-world experiences” (Torre 2017, 103). Animated works can easily capture ephemeral moments, thoughts, or feelings, giving them a manifestation in a physical or digital medium. Finally, Torre also draws upon Jungian psychoanalysis, positing that animation often taps into universal themes, archetypes, and symbols that have the potential to resonate deeply. When we witness these symbols and themes in animation, they reinforce our understanding and memory of them, creating a cultural feedback loop that strengthens our collective memory.

Expanded Animation and Memory

While the above-mentioned insights have mostly been applied to animation films that are projected on a two-dimensional screen and follow a linear narrative, it is remarkable that very little has been written on the connection between memory and expanded forms of animation. As has been documented by Buchan (2013) or Smith and Hamlyn (2018) among others, in the past two decades animation has increasingly expanded its reach, and begun to include media and platforms that were traditionally not considered a part of the cinematic apparatus: installation art, interactive systems, virtual and augmented reality, and even performative elements. Especially the embodied and haptic forms of expanded animation, which often revisit analog techniques and proto-animation devices such as the zoetrope, have fortified the material dimension of animation, and as such its connection with preservation (Stafford et al. 2002). Moreover, through nonlinear types of time-space organization (loops, mappings, interactive elements), animation’s fragmented, distorted, and volatile characteristics have been driven to a new level (Smith and Hamlyn 2018).

Though some references do connect these expanded forms of animation to embodied cognition, such observations are mostly made from a point of view of general media theory (e.g., Cholodenko 2008). There exists little documentation of works that connect the creation of experimental animated works to a theoretical reflection on the above-mentioned cognitive processes, using for instance an art-based research method. Though one often encounters artworks that question the material dimensions of animation, usually in the form of an installation (for instance, the kinetic sculptures of Gregory Barsamian or Eric Dyer) only rarely are these elements explicitly linked to the operation of cognition and memory. Some notable works of expanded animation projects that cover the topic of memory are Melting Memories by Refik Anadol (Staugaitis 2018), using EEG data to generate projected abstract animations; Sarah Sze’s immersive installations that aim to trigger personal everyday life memories, for instance, ‘Timekeeper’ (Balsom and Sze 2023). Going back further in history, one can argue that Stan VanDerBeek’s ‘Movie-Drome’ is also rooted in the use of memory, as a collage of images, videos and animations that can be considered an associative, whimsical means of communication (Stan VanDerBeek Archive, n.d.).

In the remainder of this paper, we will make a first step towards generating an art-based understanding of the connection between expanded animation and memory. We will describe the theoretical foundations and artistic results of ‘Expanded Memories’, a project that takes the form of a cross-disciplinary collaboration between researchers from different backgrounds: animation, game design, visual art, interaction design, philosophy, art preservation and digital art. We function as an art collective[i] whose participants are united by a focus on two elements: (1) a fascination for hybrid forms of animation that combine analog and digital elements; (2) a belief in the idea that creating (expanded) animation can teach us valuable (philosophical) lessons about the relationship between humans and technology.

The project has proceeded in different phases. First, based on a number of initial conceptual and theoretical sessions, each of the participating artists created, on their own, one or more works inspired by the question of memory in animation. This resulted in a diversity of early prototypes, connected by the idea of placing animation in a material and/or spatial context. Some of these works took the form of VR-generated models that were 3D-printed into tactile objects, others of loop-inspired video installations, or mechanically operated shadow-casting devices. (Some examples will be described further on.) Second, in a later stage, we would share and pass on our artworks to the collective, after which others would reimagine, adapt or recreate them: for instance by adding different textures or visual aesthetics to a mechanical installation made by one of the other researchers. To facilitate this cross-pollination as artistic research practice, not only the artistic outcome was disclosed within the group, but also the entire process leading to the works — which is typically kept private or is only disseminated in a highly ‘curated’ form — such as sources of inspiration, technical plans, code, sketches and intermediate files. Following this collaborative method, our works were continuously sent back and forward between tangible (physical) and volatile (digital) artifacts, and between the subjective positions of different practitioners. In this sense, we aimed to mimic, within our process, the principles of de- and re-contextualization that characterize the operation of memory (e.g., Walden 2018).

Finally, we regularly participated in exhibitions, usually accompanied by a presentation of our theoretical insights. Throughout these reflective moments, we observed, after a few iterations, that our focus of attention had gradually shifted from the creation of analog animation installations, towards, more specifically, the creation of works that entail an interplay between light and shadow. We noticed that many of our animated works involved the display of a device that casts a moving shadow or a kaleidoscopic light-play on a surface, for instance by placing a strobe light in the middle of a rotating cylindrical object. This led us to rethink our approach to the relationship between animation and memory. We started digging deeper into the question of how a process of dematerialization such as shadow casting can be linked to notions of cultural preservation and cognition. In this effort, we developed a visual style that relied strongly on Arabic and Persian calligraphy. In the next section, we will present our conceptualization of the link between shadow, light, and memory; after which we will discuss a number of the resulting creations and their connection to these theoretical insights.

Shadow, Art and Memory

The Light/Shadow dichotomy has been used since the very inception of Western Thought in relation to the ontological concept of ‘difference’. What follows aims to be a sketch of its history and not a full survey of the problem, which naturally will result in ‘derive’ on the subjects and objects we are presenting here. In The Republic, Plato imagines an early human society imprisoned in a cave. These people can only stare at the wall of the cave, which is covered in shadows cast by objects from the outside world. These cave inhabitants are unaware that an outside world even exists: they are only in contact with shadows, mere umbra of things. They have to be freed from their bonds, turn around, and face the brightly lit world in order to realize that they were only exposed to silhouettes projected by the light coming from a fire. Only by facing the light that projects a shadow can they come to a true understanding of the world. In Plato, the shadow is the trace, the absence made present in its incompleteness.

In this paragraph we muse over the concept of the shadow and its relation to memory – shadow as the inner and the outer, the latent and the manifest, the hidden and the revealed. “When painting first emerged, it was part of the absence/presence theme (absence of the body; presence of its projection). The history of art is interspersed with the dialectic of this relationship” (Stoichita 1997, 7). The emergence of Western representational painting is an expression of memory, an attempt to make the absent materially present via the sketch that can be traced when drawing, outlining a shadow of anything. Shadows are the very essence and one of the first human attempts to fix something in time and in its singularity. A shadow, when fixed, is the first doppelgänger human invented: a ‘thing’ made double, a first copy of the world. Shadow is the eidos: our figure of a singular thing but without ‘the thing itself’. We can trace this idea back to Greek and Latin Philosophy, for instance in Pliny the Elder, Natural History, XXXV. 11: “The art of painting at last became developed, in the invention of light and shade, the alternating contrast of the colours serving to heighten the effect of each. At a later period, again, lustre was added, a thing altogether different from light. The gradation between lustre and light on the one hand and shade on the other, was called ‘tonos’; while the blending of the various tints, and their passing into one another, was known as ‘harmoge’”. Later on, we find it in the rhetorician Quintilian in his Institutio oratoria, X, ii, 7, where we can read, in the line of Pliny “The art of painting would have been restricted to tracing a line round a shadow thrown in the sunlight”.

The question of memory as the presence of an absence first emerged with the theory of the unconscious laid down by the early psychoanalysts. In his book History of the Shadow, Stoichita describes the relationship between presence and absence in the context of art and representation. According to Stoichita, the absence/presence issue is intrinsic to the painting’s origins, especially when it comes to representational art. The primary premise of this theme is that while the corporeal body is projected onto the canvas, it is also absent during the painting process. Painting essentially becomes a method for bringing the absent into the material world. According to Stoichita, this link has played a dialectic role throughout the history of art. In their quest for representation, artists perform a difficult dance between distilling the essence of the absent and making it material in their creations. A key component of the artistic journey is this dynamic investigation of presence and absence.

Furthermore, Stoichita suggests that with the development of psychoanalysis, the issue of memory as the presence of an absence gained prominence in both art and thought. The concept of the unconscious, which is where suppressed memories and desires live as absences in the conscious mind, was first presented by early psychoanalysts like Sigmund Freud. This unconscious world represents the idea that memory is more than just a recollection; rather, it is the existence of something absent that frequently has a significant impact on mental and behavioral states in people. Stoichita ponders the profound and enduring relationship between representation, memory, and the oscillation between absence and presence in the rich tapestry of art and human experience. It underscores the ways in which art and memory intersect, providing insight into how art has been a vehicle for making the absent palpably present throughout history.

According to Freud (1917), memories emerge from the unconscious as a trace of a repressed material. He suggests that memories and experiences are not neatly stored away in the mind but can resurface in various forms, including slips of the tongue, forgotten details, and unresolved grief. Memories, especially those connected to repressed or unconscious material, can have a profound influence on our behavior and mental well-being (Fiorini 2009). His pupil, Carl Jung, elaborated on this idea by presenting his theory of the shadow. Jung sees the shadow as the repressed and often hidden part of the human psyche. It is the aspect of the self that is often kept away from the persona, the self that is usually presented to others (Jung 2013). Psychoanalysis generally sees the shadow as an absence of sorts, one that often makes itself present through memory, slips of the tongue, and certain uncontrollable impulses. The inner workings of the unconscious are thought to be elusive to the outer representations of the consciousness. McMillan (2018) reflects on the associations of the latent neural networks of the Jungian conception of the unconscious in light of Deleuze’s concept of rhizome (Deleuze and Guattari 1980). He posits that the free association of images, archetypes, patterns, and motifs is emergent in nature, and surfaces to cognition out of an absence (McMillan 2018). Therefore, memories, like shadows, are an interplay between presence and absence.

Laura U. Marks presents the idea of the ‘Batin’ and ‘Zahir’ (ظاهر والباطن) in the context of media art, explaining how these terms that are derived from Sufism (Islamic mysticism) collide with contemporary artistic works and practices. Marks’ examination of the Batin and Zahir demonstrates the diverse aspects of media art, particularly with regard to the interplay between the revealed and the concealed. The terms ‘Batin’ and ‘Zahir’ originate from Sufism, which is Islam’s mystical branch. ‘Zahir’ denotes the outward, the visible, and the exoteric, whereas ‘Batin’ stands for the hidden, the esoteric, and the internal. According to Marks, media art merges these two domains, making it harder to distinguish between what is revealed and what is kept hidden. In the context of media art, ‘Batin’ encapsulates the underlying processes, algorithms, and digital structures that often remain concealed from the viewer’s immediate perception. ‘Zahir’, on the other hand, pertains to the observable and sensory aspects of the artwork, the visual and auditory experiences made accessible to the audience (Marks 2011).

In this sense, the history of shadow or the presence of the shadow never disappears from the human mind and is still a problem, even in digital technologies: “All new media objects (images, movies, sound, actions) are the perceptible manifestation of code. They unfold from code easily and without tension because that is what they are usually meant to do” (Marks 2011, 246). Marks contends that media art enacts an interplay between the ‘Batin’ and ‘Zahir’, creating a space where the concealed and the visible coexist. This convergence challenges traditional modes of perception and representation, inviting viewers to engage with the artwork on multiple layers. The artist’s manipulation of digital media and the audience’s interactive involvement both contribute to this dynamic interplay. Ultimately, Marks’ discussion underscores the intricate relationship between Islamic mysticism, magic thinking in Renaissance Philosophy, and contemporary media art, emphasizing how media art functions as a site of convergence, where the Batin and Zahir, or in Hegel terms “pure light and pure darkness” intermingle to produce rich and multilayered experiences. Her exploration sheds light on the profound implications of these mystical concepts within the realm of artistic expression in the digital age (Marks 2011) but that have references in Renaissance and continue to make presence till the present days.

The myth of Narcissus had enlarged the problem of representation, linking art, memory and shadow in relation to the issue of self-representation. Narcissus’ shadow appears as an epiphenomenon of the question concerning the origin of the artwork. At the same time, it functions like a projection but with precise content, because every self-representation needs resemblance. Leon Battista Alberti in De Pictura dwells on this and points out that this ‘fine trace’ has become a human obsession in copying by appropriating the self. The ancient problem of shadow and reality revives here: “All the shadows of the man are delimited”, says Alberti. The exercise of painting Narcissus is, according to Alberti, an act of re-animation. Giordano Bruno, on the other hand, tries to solve this ‘double image’ issue by suggesting to use of language to describe images, and, conversely, images to illustrate language (Bruno [1582]). In this conceptualization, shadows and mirrors of the self are projections, and at the same time they are animations; the shadows of self-projection always imply the idea of animating, of creating images that bear verisimilitude. Technical possibilities of the late XIX century already allowed for a relationship to be established between reality, image, and the self, which led to the idea of an absolute copy of the totality of the world. This idea of an absolute copy can thus be traced back to the very beginning of the animation medium, which links this project to Media Archaeology in its purest sense: “Media archaeology is introduced as a way to investigate the new media cultures through insights from past new media, often with an emphasis on the forgotten, the quirky, the non-obvious apparatuses, practices and inventions” (Parikka 2012, 3).

Expanded Memories: Artworks and Their Relation to the Cognitive and Psychological Processes of Memory

Inspired by these concepts, and in a (cross-cultural) dialogue with one another, the application of our creative method resulted in a variety of works, each in their own way using the principle of light/shadow casting, in order to explore the (de)material(ized) relationship between animation and memory. The juxtaposition of these artifacts in an exhibition context has resulted in a number of expositions, among others at the Royal Academy of Art in Antwerp (April 2023), and the INSHADOW Lisbon Screendance Festival (December 2023). Although for analytical reasons we discuss each of these artworks separately, it is important to note that they are all the result of a collective effort, and can be best understood in relation to one another. We believe that these works should be considered as a collection, each showcasing a different side of the same underlying artistic concept.

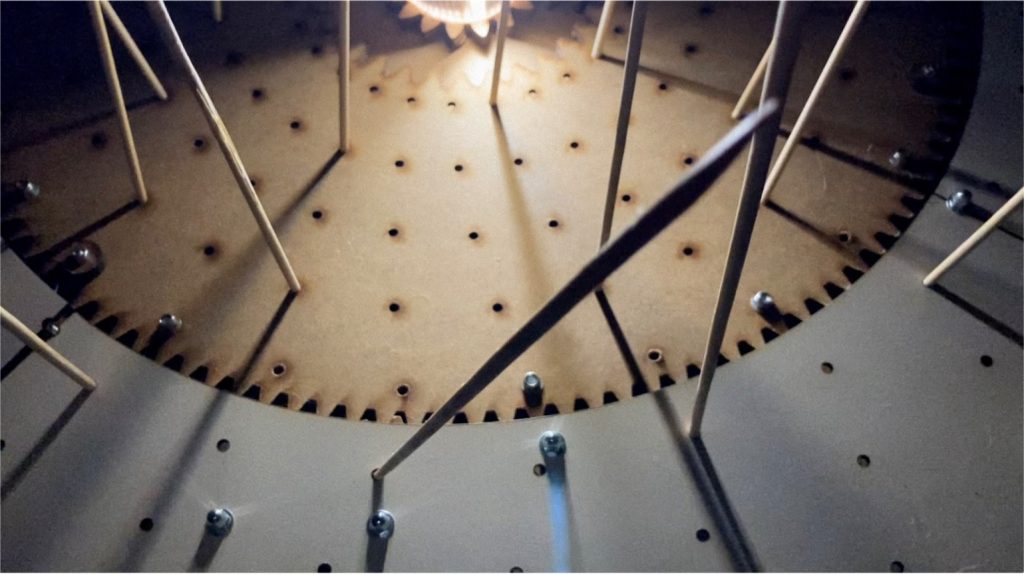

This work materializes the concepts of record/testimony/presence/memory in its combination of shadows, words, and sound. The piece consists of a mechanism that rotates a ray of light, limited in width, like a lighthouse, which unveils words and casts shadows of wooden sticks placed on the rotating plate of the object. These sticks are interaction pieces, as they can be removed from or added to the existing holes in the plate to change the visual and audio spaces.

A generative sound environment was created, resulting from the random composition of five sets of five loops, which are activated/deactivated by the play of shadow and light. The sound interference develops an abstract overarching narrative, built from an A minor chord, transforming itself throughout five sound entities, always having as root a very simple rhythm in eighth notes. Depending on the context, this results in a counterpunctual interplay, sometimes chaotic, sometimes harmonic, with the dispersions and compressions of light and shadow. The visual elements complete the sonorous crucible, either in a very dense or anarchic way or even playful and childish.

The notion of a ‘machine’, which is featured in the title, is at the center of this piece. All of its parts, even though they have been cared for in aesthetic terms, fulfill a function. They are part of a mechanism that aims to construct a scenic space made up of moving shadows, obtained by intermittently concealing a spotlight by means of slender wooden cylinders inserted into multiple holes in a rotating plate. Spotlight and plate rotate in opposite directions, sharing the same center. The physical limits of the machine are defined by an immovable ring that helps to contain the central plate, which fixes the system of wheels responsible for the movement of the plate and a mechanical switch. This ring also protects the light sensors that are responsible for sending light intensity values to the computer system with each activation of the switch per complete turn of the platter.

The computer system consists of an Arduino UNO (AU) and a Motor Shield (MS) associated with a DC motor gear and a WAV trigger (WT). Reducing the interaction between these three elements to the essentials, we have the MS which is controlled in ON/OFF logic by the AU, which in turn sends these orders according to the reading it receives from the mechanical switch: when pressed, the motor stops. In addition to immobilizing the engine, the switch activation triggers a counter in the AU that defines the engine stop time, designed to allow interaction – removing and/or placing the wooden cylinders – and the stable reading of the light sensors. The average of the values sent by these sensors will define how many of the five sets of loops stored in the WT will be activated simultaneously: the lowest range on a scale of five will activate just one, while the highest will result in five loops being heard simultaneously. In other words, the more light the sensors receive, the fuller and more intense the sound space becomes. It is also important to note that the loops in each group are randomly selected from a sample of five, in order to ensure a fresh and unpredictable sound experience.

Like any interactive work, this Shadow Machine needs an intervener, an active spectator, a spect-acteur (Poissant 2003) who is available to interact and discover the mechanism and its output. This results in endless scenic variations, unrepeatable if we take into account the oscillations of a mechanism that embraces gaps and inaccuracies. This process of co-authorship that the artists delegate to those involved does not end there. The machining plans for the various components, largely obtained by laser cutting, as well as the programming and electrical circuits, will be shared with the general public via various files and an ‘assembly manual’. The aim is to extend the principle of co-authorship to the literal transformation of the work.

Artifact 2. Kalam-Machine (كلام, talk)

Repetition is perhaps the single-most used technique of memorization across time and cultures, whether it is for the purpose of education, indoctrination, or because of routine activities or encounters. There is nonetheless a major difference between a deliberate exercise of memorization (called “rote learning”) through a conscious and intentional process of repetition, and the spontaneous, unintentional retention of information without deliberate effort – or ‘incidental memory’. While rote learning is deliberate and conscious, involuntary memory involves the retention of information that occurs naturally through repeated exposure or experiences. Both types of memory have their uses and can complement one another in various aspects of learning and daily life. The Kalam-Machine project draws on both of these definitions of memory. It is also a hybrid artwork merging classic or traditional practices (sculpture, pottery, calligraphy) with digital media forms (3D printing, VR). The project went through four stages of development with Diaa Lagan as the main artist with the help and input from John Buckley. First, we engaged with probably one of the world’s oldest proto-animation devices: a ceramic bowl found in the city of Sookhteh in Iran.

This bowl’s ornamentation depicts a wild goat jumping up to eat the leaves of a tree in a series of images representing the animal’s movement in five stages, in a way that is strikingly reminiscent of zoetropes. Taking inspiration from the bowl, Diaa Lagan organized a range of workshops with graphic art students at Dún Laoghaire Institute of Art, Design and Technology (IADT), exploring the techniques of holey pottering, Arabic calligraphy, and shadow casting. Expanding on these experimentations, the artist then created a visual pattern based on a memory of his personal daily habit of drinking coffee on a balcony at home, in Aleppo (Arabic: تعال, القهوة جاهزة على البلكون; English: come on! coffee is ready on the balcony). At this stage, the work was concerned with the legacy of decorative writing and Arabic calligraphy as an identity practice and form of expression of memories. In the third stage, John Buckley and Diaa Lagan studied the properties of the Dreamachine, a device imagined by Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs in the 1960s, also reminiscent of the zoetrope. The Dreamachine is a flickering light art device, rotating at a specific speed and frequency (78 rpm speed, light frequency of 20.8 Hz) creating for the user who keeps their eyes closed, a state of relaxation, leading to creative inner visions or hallucinations (ter Meulen, et al. 2009). In order to recreate the Dreamachine properties, the 2D sentence depicting the artist’s past coffee-drinking habit is turned into a three-dimensional object – a cylindrical sculpture. Spinning on a turn-table with a light bulb in the middle, casting dynamic hypnotic shadows in the space as it rotates, the sentence-turned cylinder replicates the original Dreamachine, while at the same time, the routine expression it depicts is now expressed through a repetitive kinetic motion. As the project focuses on hybrid analog and digital animation, we used 3D printing to create prototypes, testing them manually. Through regular online meetings with the Expanded Memories collective, sharing ideas and processes, we found a connection to collaborate with José Neves, by adding elements of the Kalam-Machine to the Shadow Machine. During an online and in-person workshop, we decided to break down the Kalam-machine into separate parts so they could interact with the performative elements of the Shadow Machine. The workshops also allowed us to test various techniques of shadow casting, depending on distance and light intensity, and by overlayering sections of the original Arabic calligraphy.

In a recent fourth stage, the Kalam-Machine has been turned into a VR experience, which expands again the projects’ exploration of memories in an imaginary environment. This VR experience allows the users to enter an immersive world, where they can move around and explore different spaces, from a 360-degree landscape photo to a sphere bubble. Users are able to manipulate the light source, changing the shape and form of the shadows within the sphere. This creates a dynamic and interactive experience allowing to play with light and shadow in a surreal and dream-like fashion.

Artifact 3. Proto-animation meets VR

With the proliferation of media art, proto-animation devices have attracted renewed attention, often from the perspective of media archaeology (Huhtamo and Parikka 2011). As an academic discipline, media archaeology lacks an overarching methodology or institutional framework, though its proponents are united in denouncing a linear, teleological view of media history, aiming to identify the old in the new, but also the new in the old (Zielinski 2006).

The method of resurrecting the old in and through the new, also prompted our artistic research, integrating the underlying principles of the phenakistoscope and zoetrope within a VR environment. In initial prototypes, both proto-animation devices were created simultaneously alongside one another. The zoetrope has its images oriented horizontally on a paper strip, placed inside a slotted cylinder. In the phenakistoscope, however, the images are placed on a vertically oriented slotted disc. In later experiments, a three-dimensional hybrid emerged, combining both planes, either in the form of an animated sculpture or a VR animation. Remediating the ‘phenakisti-zoetrope’ into VR offers a different and unique perceptual experience to the viewer, who is at the center of the ‘device’ looking outward.

Adding a third dimension allows the images to cast shadows, an aspect typically absent in the original devices. This opens room for experimentation with the ambiguous relationship between the images casting the shadow and the projected shadow itself. Drawing inspiration from the fear of shadows at twilight, inherent to childhood fantasy, we explored a wide range of options by applying the principles of anamorphosis: depending on the position of the spectator, the casted shadow animation would become skewed. We argue that this aesthetic effect reflects both the subjectiveness and the distortion and decay that characterizes the processes of memory (re)construction. In this sense, we observe that VR functions as a creative research tool facilitating different approaches towards including the spectator as a mediator of the relationship between light/shadow and the three-dimensional characteristics of the zoetrope/phenakistoscope.

Artifact 4. Anamorphic Shadow Animation

Simultaneous with the creation of artifact 3, another artwork was created that took anamorphic shadow casting as its central focus, in a combination of VR and 3D printing techniques. This installation immerses the audience in a space filled with pulsating shapes visible through a VR headset. These abstract forms constitute an animation loop that seems, at first glance, unrecognizable and unworldly, accompanied by a tense and eerie soundscape. Only as the spectators’ gaze faces the floor do they notice that the casted shadow takes a more conventional, easily recognizable form, unveiling a hunched creature’s walk cycle.

This initial prototype was fully generated within a virtual production environment, through the arrangement of abstract 3D parts using Gravity Sketch software. In the next step, a transition was made to the tangible using 3D printing. Frames of the creature’s movement, printed in resin, were displayed on a rotating plexiglass plate. With the application of a synchronized stroboscopic light, this setup physically projects the creature’s animated shadow, again creating an anamorphic distortion, depending on the spectator’s physical position. Contrary to artifact 3, viewers witness this spectacle externally, enveloped in the creature’s ominous progression.

Significant insights had been obtained from the shadow-centric narratives of artists like Tim Noble & Sue Webster, and Kumi Yamashita. Similarly, we drew inspiration from the sensory environments cultivated by teamLab’s installations, attempting to blur the lines between digital and physical environments. The work also acknowledges foundational animation techniques pioneered by for instance Eadweard Muybridge’s Zoöpraxiscope (1879). The creation of a spatial installation was additionally informed by Antony Gormley’s reality-challenging sculptures Quantum Clouds (2000-2009), interpreted through the lens of animated anamorphic shadows. In general, we could position this work within the tradition of the Expanded Cinema art movement of the 1960s and 1970s, with artists like Stan VanDerBeek offering a radical, communal, multimodal viewing experience, inspiring the spectator to break free from traditional formats.

Artifact 5. Dream-o-trope: A Crossover between the Proto-animation Device and the Dreamachine

As described above, during later iterations the aspect of cross-pollination and co-creation was foregrounded in the Expanded Memories project. The process of each artist/researcher, taking the form of ideas, sketches, prototypes, simulations, and theoretical reflections, was shared as ‘open source’ material through the project’s Discord group, which functioned both as a research diary and communication platform. At a certain point, this resulted in a synthesis between two different branches of the project, taking the zoetrope (artifact 3) and the Dreamachine (artifact 2) as their respective starting points. Previous research acknowledged the distinct morphological similarities between both (Lütticken 2010), and Erkki Huhtamo (2016:76) even argued that the construction of the Dreamachine was likely derived from the zoetrope.

Despite their similarities, the perceptual differences between both apparatuses explain why only a few artists or researchers have explored the connection between both devices. Typically, the viewer experiences the Dreamachine with both eyes closed, which is not the case with the zoetrope. Central — both figuratively and literally — to the Dreamachine-dispositif is a high-power incandescent bulb at the center of the cylinder. The combination of the cutouts and the rotation speed of the record player yields a flicker ratio between 8 – 12 Hz, which is held responsible for stimulating alpha waves in the brain (Ter Meulen et al., 2009). So, is there a possible connection between them other than the cylindrical assembly?

In Nik Sheehan’s documentary film on the Dreamachine, FlicKeR (2008), filmmaker Kenneth Anger states that “the oldest alpha-wave machine or Dreamachine was staring into a fire”. This act of fire gazing can also be considered “a multisensory, and consequentially highly individualized, form of animation” (Sullivan, 2017: 4) and is thus linked to animation devices from the Victorian era. Specifically, this perceptual sensation of flickering is inherent to the zoetrope, in its original manifestation due to the alternating succession of light passing through the slits or blocked by the drum itself.

Typical for proto-animation devices such as the zoetrope and phenakistoscope is that the images are arranged radially (Dulac & Gaudréault, 2004). Within our adaptation, however, the shutter is outsourced to a strobe light, as a result of which the full height of the cylinder can be used. Although uncommon in 19th-century proto-animation devices, this type of image placement can be traced back to much older image technologies. In Roman antiquity, victory columns, such as Trajan’s column or the column of Marcus Aurelius in Rome, contain a narrative frieze with sequential images — thus resonating with the Sookhteh bowl mentioned previously in section 4.2 — organized in an ascending helix forming a narrative. Trajan’s column thus recounts the Dacian war, although it remains unclear whether the viewer was forced to walk around the column to make sense of the narrative (Davies 1997: 44).

In our own construction, the cylinder is obviously rotating, making the images appear moving upward or downward, relative to the rotation direction. In Lightwalk, every winding of the spiral contains 32 images, which requires a higher strobe frequency than the 8-12 Hz of the Dreamachine to yield a fluent animation. Therefore, Dream-o-trope, the integrated work that uses these principles, contains fewer images, 13 per winding. The imagery drew inspiration from the theme of Sufi meditation, which plays a central role in the research of Diaa Lagan. Dream-o-trope explores a meditative, conceptual form of tangible light/shadow-animation. This work reflects on the universal human strive to achieve a state of oneness, which is fundamental to many spiritual and philosophical traditions across the globe. On the material level of the shadow, the machine itself, the rotating crescent shapes move closer but remain separate. Only in the blurry edges of the projected light, they can join as one.

Artifact 6. Object, Film Analogue, and Digital Projection

Memory is a form of action. Even though remembering is related to the past, we rewrite our memories in the present when we recall them. Animation transforms time and space and can be considered a tool that recreates and re-edits the fragmented notions of time that characterize the human cognitive process. In this sense, animation is highly suited as a means of memory preservation as it embraces the unreliability of memories in an honest way, excluding itself from issues of credibility of documentation, which other media such as photography and video are undergoing due to their nature of having a referent in real life.

The ‘Object, Film Analogue and Digital Projection’ project uses animation production as a process of memory consolidation. The work can be seen as a personal memory extension that preserves the irrational and incomplete memories of the artist towards the house where he grew up. The work recalls (by using 16mm documentation film footage) and recreates (by using analog animation techniques such as scratch animation) the space and time of these memories, ultimately overwriting, re-editing, and re-materializing them in the form of an art installation.

The work presents a combination of looped digital videos, projection of an analog film roll, and exposition of a physical object. The digital videos consist of 4 screenings, each presenting a chapter that enacts a specific memory the artist had as a child in his house. The analog film roll contains the raw materials that the digital videos have been based upon, using a different editing and playback sequence. As such, the dialogue between both questions the accuracy, embeddedness, and subjectivity of memory processes, externalizing them in different material forms. The object installation is displayed in the same space where the analog and digital films are projected to connect, juxtapose, and bring the viewers back and forth between tangible (physical) and volatile (digital) space.

Conclusion

These cases demonstrate that an artistic and experimental approach to animation can produce new insights into the relationship between animation and cognition, specifically in connection to memory. In conclusion, we reflect on our approach and identify new pathways to be further explored by artists and researchers.

First, on the level of process, we note that a collaborative approach can produce valuable results in exploring the tension between linearity and fluidity of the animation medium, as well as the continuous shift between subjective perspectives that characterize the fields of cultural preservation and archiving. In particular, we want to highlight the benefits of adopting an open-source approach: in sharing all our sketches, models, plans, and technical descriptions with one another, our online communication platform was soon transformed into a hybrid repository of interconnected nodes of knowledge, from which all artists involved could draw inspiration and create their own connections. Conceptually, it can be argued that this collaborative method, focused on remixing each other’s work, shows similarities with the cut-up method of semi-randomized textual organization, as developed by William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin in their collaborative book The Third Mind.

Second, on the level of materiality, our practice initially revolved around creating physical objects using a texture that refers to a specific cultural background or tradition, effectively serving as a vehicle of that tradition. The artistic-experimental approach further carried us on an exploration of shadow/light casting, which ultimately resulted in a blending of Middle Eastern and Western artistic-philosophical traditions, effectively revisiting both and putting them in a dialogue with one another. On the formal level, the component-based approach of creating animation machines (as indicated in the titles of many presented works) can be considered an extension of our open-source practice, establishing a connection between our works and the operation of memory processes. In the same line, inviting the spectator to participate in these works reinforces the processes of intersubjectivity that characterize both our collaborative method and the practice of cultural-historic preservation.

Third, in relation to this, the practice of putting the spectator in an anamorphic relation to the exhibited shadow animations was found to be a powerful technique to externalize the incomplete and distorted nature of processes of recollection. Memories have a tendency to be volatile and to become skewed over time and in relation to their specific context. The use in our artworks of this basic form of interactivity provides us with an effective format to reflect upon this. In general, our shift of focus from processes of materialization (archivation/preservation) towards dematerialization (the volatility of light and shadow interplay) enables us to discover new layers of meaning in the connectedness of the animated medium and human cognition.

Finally, the use of different installation formats enabled us to explore alternative types of time-space organization in ways that are not easy to achieve within linear, screen-based animation. Regarding temporal organization, the use of loops that are continuously being de- and re-contextualized, in dialogue with the exposition space, as well as with the input of the spectator, creates a sense of variation-in-repetition that relates to several texts on the cognitive functions of animation, at the same time as inviting the spectator to enter an introspective, at moments meditative experience. Regarding spatial organization, a key finding that came forward regards the juxtaposition of (physical/analog) objects and the (digital) mapping of their movement or shadow onto a wall or other surface. The resulting relationship between different sizes and proportions of the same animation cycle was found to create a tension reminiscent of the phenomena of distortions and aggrandizing that characterize recollection and historic preservation. A cylindrical rotating object can be displayed in its true, usually rather small size and simultaneously its movement can be blown out of proportion in the size of the video mapping or shadow play that it is put in relation to.

This project showcases the rich and versatile potential of artistic research, furthering our knowledge of the philosophical and cognitive foundations of animation while simultaneously opening new pathways for animation artists to move beyond the traditional boundaries of their medium. In this sense, we hope this project can inspire future collaborative and multidisciplinary encounters between scholars, researchers, artists, and practitioners, aiming to strengthen animation’s growing status as a maturing artistic form.

Steven Malliet is a lecturer and researcher at LUCA School of Arts and an Associate Professor at the University of Antwerp. He is a member of the academic board of the Re:Anima Erasmus Mundus Joint Master Degree (EMJMD) in Animation.

John Buckley is a digital artist, designer, researcher and educator, lecturing in 3D Modelling, VFX and VR at the Institute of Art, Design and Technology.

Guido Devadder is an artist and PhD candidate at LUCA School of Arts in Brussels where he also teaches at the Department of Audiovisual Arts.

José Carlos Neves is a researcher and teacher in the areas of Media Arts, Interaction and Design at Lusófona University. He holds a PhD in Communication Studies (Interactive Arts).

José Gomes Pinto holds a Ph.D in Philosophy: Aesthetics and Art Theory and teaches in the School of Arts, Architecture, Arts and Information Technologies at Lusófona University.

Fuad Halwani is a Lebanese scriptwriter, media producer and published doctoral researcher at Universidade Lusófona. His research focuses on Shadow Narratives in media art.

Diaa Lagan is a multidisciplinary artist based in Dublin and a PhD candidate at Universidade Lusófona.

Judith Pernin is a Post-doctoral researcher at the Institute of Art, Design and Technology and a coordinator of Expanded Memories.

Veronika Romhàny is an artist and PhD candidate at LUCA School of Arts who investigates collaborative digital art practices.

Thanut Rujitanont is an animation artist holding a joint master’s degree from the Re:Anima Erasmus Mundus program. He uses animation to explore the crossover with various art forms and scientific approaches.

João Trindade is a musician and professor. He holds a PhD in Communication Studies and has ‘forgotten sounds’ as the basis of his research and sound production.

Gert Wastyn is a PhD candidate at LUCA School of Arts and a multimedia artist, teaching and researching the field of Extended Reality within Expanded animation.

Works Cited

Alice. Dir. Jan Švankmajer. Film Four International – Condor Films, 1988.

Balsom, Erika, and Sarah Sze. “Sarah Sze’s Experiments of Collective Timekeeping.” Frieze, no. 235, 2023, www.frieze.com. Accessed 3 May 2024.

Body Memory. Dir. Ülo Pikkov. Nukufilm, 2011.

Borgdorff, Henk. The Production of Knowledge in Artistic Research. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2010.

Bruno, Giordano. On the Shadows of the Ideas: Comprising an Art of Investigating, Discovering, Judging, Ordering, and Applying, Set Forth for the Purpose of Inner Writing, and Not for Vulgar Operations of Memory. Arcane Wisdom, 2020.

Buchan, Suzanne, editor. Pervasive Animation. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2013.

Cholodenko, Allan. “The Animation of Cinema.” The Semiotic Review of Books, vol. 18, no. 2, 2018.

Coessens, K., D. Crispin, and A. Douglas. The Artistic Turn: A Manifesto. Orpheus Instituut; Leuven, Belgium, 2009.

Davies, Penelope J. E. “The Politics of Perpetuation: Trajan’s Column and the Art of Commemoration.” American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 101, no. 1, Jan. 1997, pp. 41–65. doi:10.2307/506249.

Dear Angelica. Dir. Saschka Unseld. Oculus Story Studio, 2017.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guatari. Mille Plateaux. Éditions de Minuit, 1980.

Dulac, Nicolas, and André Gaudreault. “Circularity and Repetition at the Heart of the Attraction: Optical Toys and the Emergence of a New Cultural Series.” In The Cinema of Attractions Reloaded, edited by Wanda Strauven, Amsterdam University Press, 2006, pp. 227–44. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt46n09s.17. Accessed 29 Oct. 2023.

Fiorini, L. G., editor. On Freud’s “Mourning and Melancholia”. 2nd ed., The International Psychoanalytical Association, 2009.

FlicKeR. Dir. Nik Sheehan. Makin’ Movies Inc., 2008.

Freud, Sigmund. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XIV, On The History of Psycho-Analytic Movement, Papers on Metapsychology and Other Works. Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis, 1914–1916. www.sas.upenn.edu/~cavitch/pdf-library/Freud_MourningAndMelancholia.pdf. Accessed May 2024.

Gysin, Brion, and William S. Burroughs. The Third Mind. Grove Press, 1978.

Huhtamo, Erkki, and Jussi Parikka, editors. Media Archaeology: Approaches, Applications, and Implications. University of California Press, 2011.

Huhtamo, Erkki. “Art in the Rear-View Mirror.” In A Companion to Digital Art, 2016, pp. 69–110. doi:10.1002/9781118475249.ch3.

Jung, Carl G. The Undiscovered Self. Routledge and Kegan Paul First, [1957] 2013.

Lizzini, Olga. “Ibn Sina’s Metaphysics.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Fall 2021 Edition, edited by Edward N. Zalta, plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2021/entries/ibn-sina-metaphysics/. Accessed 3 May 2024.

Lütticken, Sven. “Transforming Time.” Grey Room, no. 41, Oct. 2010, pp. 24–47. doi:10.1162/GREY_a_00009.

Marks, Laura U. Enfoldment and Infinity: An Islamic Genealogy of New Media Art. Design and Culture, vol. 3, issue 3, 2011.

McMillan, Christian. “Jung and Deleuze: Enchanted Openings to the Other: A Philosophical Contribution.” International Journal of Jungian Studies, vol. 10, no. 3, 2018, pp. 184–198.

Paprika. Dir. Satoshi Kon. Madhouse, 2006.

Parikka, Jussi. What is Media Archaeology? Polity Press, 2012.

Patience of the Memory. Dir. Vuk Jevremovic. Canvas Production, 2009.

Plato. Timaeus. Harvard University Press, 1929.

Poissant, Louise, editor. Esthétique Des Arts Médiatiques. Université du Québec, 2003.

Quintilian. The Institutio Oratoria of Quintilian. W. Heinemann; G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1921.

Raami, Asta. Intuition Unleashed: On the Application and Development of Intuition in the Creative Process. Aalto University Press, 2016.

Schön, Donald A. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. Temple Smith, 1992.

Skazka Skazok/Tale of Tales. Dir. Yuri Norstein. Soyuzmultfilm, 1979

Smith, Vicky, and Nicky Hamlyn. “Introduction.” In Smith, Vicky, and Nicky Hamlyn, editors. Experimental and Expanded Animation: New Perspectives. Springer, 2018, pp. 1-17.

Stafford, Barbara M., Frances Terpak, and Isotta Poggi. Devices of Wonder: From the World in a Box to Images on a Screen. Getty Research Institute, 2001.

Stan VanDerBeek Archive. Movie-Drome. 1965. www.stanvanderbeekarchive.com. Accessed 29 Apr. 2024.

Staugaitis, L. “Melting Memories: A Data-Driven Installation that Shows the Brain’s Inner Workings.” Colossal. 25 Apr. 2024. www.thisiscolossal.com/2018/04/melting-memories/.

Sullivan, Anne. “Animating Flames: Recovering Fire-Gazing as a Moving-Image Technology.” 19: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century, no. 25, Dec. 2017, doi:10.16995/ntn.792.

Ter Meulen, Bas, et al. “From Stroboscope to Dream Machine: A History of Flicker-Induced Hallucinations.” European Neurology, vol. 62, Oct. 2009, pp. 316–20, doi:10.1159/000235945.

The Tale of the Princess Kaguya. Dir. Isao Takahata. Studio Ghibli, 2013.

Torre, Dan. Animation – Process, Cognition and Actuality. Bloomsbury Academic, 2017.

van Gageldonk, Maarten, László Munteán, and Ali Shobeiri, editors. Animation and Memory. Springer International Publishing, 2020. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-34888-5.Waking Life. Dir. Richard Linklater. Independent Film Channel Productions – Thousand Words – Flat Black Films – Detour Filmproduction, 2001.

Walden, Victoria G. “Animation and Memory.” The Animation Studies Reader, edited by Nichola Dobson, 2028, pp. 81-90.

Wells, Paul. Understanding Animation. Routledge, 1998.

Zielinski, Siegfried. Deep Time of the Media: Toward an Archaeology of Hearing and Seeing by Technical Means. MIT Press, 2006.

Acknowledgements: This research was developed in the context of FilmEU – European Universities Alliance for Film and Media Arts and supported in part by funding from the FILMEU_RIT – Research | Innovation | Transformation project, European Union GRANT_NUMBER: H2020-IBA-SwafS-Support-2-2020, Ref: 101035820 and the FILMEU – The European University for Film and Media Arts project, European Union GRANT_NUMBER: 101004047, EPP-EUR-UNIV-2020.

[i] We wrote this essay as a collective: everybody involved in the process of artistic creation and/or theoretical reflection has been included as a co-author.