Though critics and scholars continue to split hairs over which films best exemplify Japan’s “New Wave” of cinema from the late 1950s through the 1960s, the vast majority of works highlighted within such debates share one overarching commonality: they are works of live-action cinema. Situating animated media within a sea of scholarship celebrating handheld cameras, long takes, and location shooting proves difficult because animated films are typically created under different material conditions via dissimilar means of production. Nevertheless, animators at the time grappled with similar political and economic stressors as their counterparts making live-action cinema, including a tumultuous political climate, as well as industrial overhauls engendered by the emergence of television broadcasting. Several pressing historiographic problems arise from this discrepancy: do animated media also demonstrate “new wave” aesthetics or problematics? If so, why do they remain overlooked in such scholarship, and how might incorporating such works alter the function of the “Japanese New Wave” as a critical category in film history?

In this essay, I wrestle with the widespread omission of animated works from accounts of the Japanese New Wave by locating analogous formal and narrative elements in contemporaneous animated media. In my first section, I sketch out a set of New Wave aesthetics and problematics by closely analyzing the works and writings of Kuri Yōji, the most prolific of a trio of trailblazing independent visual artists from the early 1960s operating under the banner Animēshon sannin no kai (“Animation Association of Three”). After highlighting a number of central issues within Kuri’s unusual shorts including gender, sexuality, urbanization, and high-speed economic growth, I turn to an examination of two short films directed by Mori Yasuji (Koneko no rakugaki [1957, Kitty’s Graffiti] and Koneko no sutajio [1959, Kitty’s Studio]) during the inaugural years of production at animation studio Tōei Dōga, focusing on how labor conditions ultimately curbed formal experimentation. In my concluding remarks, I work through various contradictions and commonalities between New Wave cinema and contemporaneous animated media, and chart a course in search of an intermedial “New Wind.”

Testing the Outer Limits: The Works and Writings of Kuri Yōji

“These kinds of experiments with animation are limitless (mugen); conducting them one by one will likely take me 150 years.” – Kuri Yōji, 1963[1]

In an 1958 article entitled, “Is It a Breakthrough? (The Modernists of Japanese Film),” critic and filmmaker Ōshima Nagisa heralded the arrival of studio Shōchiku’s “Sun Tribe” (taiyōzoku) youth films, adapted from Ishihara Shintarō’s hit novel Taiyō no kisetsu (1955, Season of the Sun). Of the film that first fanned the flames of this cultural craze, Nakahira Ko’s Kurutta kajitsu (1956, Crazed Fruit), Ōshima declared, “in the rip of a woman’s skirt and the buzz of a motorboat, sensitive people heard the heralding of a new generation of Japanese film.”[2] Ōshima constructed a loose paradigm around “the three S’s – speed, thrills [suriru], and sex,” elements he believed typified the emergence of a fledgling group of cinematic “modernists.”[3] One might also add “shock,” as Ōshima drew attention to each director’s decision “to shock their audiences, rather than persuade or move them.”[4]

Working from these and other concurrent articles by the likes of Ōshima, Masumura Yasuzo, and Matsumoto Toshio, scholars in Japan and the West have constructed many riveting conceptualizations of the Japanese New Wave. Such a category overtly alludes to France’s La Nouvelle Vague, overshadowing potentially more appropriate, albeit equally amorphous terms from the Japanese language – such as angura (underground) or avan-gyarudo (avant-garde) film – for the sake of emphasizing the many connections between French, Japanese, and other national cinemas in the late 1950s and early 1960s. While probing the critical merits and shortfalls of “new waves” more broadly falls beyond the scope of this essay, I will endeavor to test the limits and function of “the Japanese New Wave” in particular by tracing parallels with contemporaneous animated media in Japan. To begin, I turn to a time and location well known to scholars of the New Wave: the year is 1960, which saw the release of Jean-Luc Godard’s À bout de souffle (Breathless) and Kuruhara Koreyoshi’s Kyōnetsu no kisetsu (The Warped Ones); the place is Tokyo’s Sōgetsu Art Center, a key hub for avant-garde art and performance, directed at the time by filmmaker Teshigahara Hiroshi. The artist, however, is less well known.

Kuri Yōji formally entered the animation industry in 1960 by establishing a filmmaking division within his independent studio Kuri jikken manga kobo. Kuri first opened his small workshop in 1958 as a 30-year-old newlywed and recent graduate of the fine arts division of Bunka Gakuin.[5] After spending two years illustrating manga and painting advertisements and calendars, Kuri decided to put his German-imported film camera to use by expanding his operations to incorporate animated television advertisements. Though television broadcasting began in Japan in 1953, it was not until the early 1960s that the majority of homes within the country owned an operating set. As a multi-talented visual artist with a penchant for the experimental, Kuri seized the opportunity to work within a field relatively unencumbered by industrial or aesthetic orthodoxy.

Within a year, two of Kuri’s early animated shorts, Fuasshon (1960, Fashion, 16mm, 5 min, B&W) and Mitsuwa sekken (1960, Mitsuwa Soap, 16mm, 1 min, B&W), had already received awards from the ADC (Tokyo Art Directors Club) and the newly established ACC (All Japan Radio & Television Commercial Confederation), respectively. In a mere half-decade, Kuri’s animation would screen in festivals and garner accolades in Venice (’62), Vancouver (’63), Annecy (’63), San Francisco (’63), Bergamo (’64), Obertshausen (’64), Kraków (’64), Locarno (’64), and Melbourne (’65).[6] To this day, Kuri has created roughly 700 animated works, with short advertisements constituting the vast majority.[7] Considering the magnitude of Kuri’s career, the dearth of English-language scholarship on his creations speaks volumes about the neglect of advertisements by scholars of film and media.

Kuri’s most prolific period as an animator was during his first decade, owing in large part to his resolve to pioneer new directions for the medium. In mid-1960, Kuri appeared on the NET (Nihon Educational Television, now TV Asahi) show Hanjōshiki no me alongside illustrator Manabe Hiroshi and designer Yanagihara Ryōhei to announce the formation of their new group, Animēshon sannin no kai.[8] Under this conceptual umbrella, the three planned to collaborate on experimental 16mm animation and to debut their work through the birth of Japan’s first festival of independent animation, to be held at Tokyo’s Sōgetsu Art Center in late November and early December of the same year. In anticipation of the event, Kuri, Manabe, and Yanagihara penned a “manifesto” in the October 1960 issue of the Sōgetsu Art Center Journal. The short text, “Toward the Creation of New Images,” reads:

How often do we see someone who boldly sets out to do something completely new succeed in making only superficial changes because they are unable to break free of established thought patterns and methods? It is because of our enslavement to old ways of thinking that we live in fear of the atom bomb and the hydrogen bomb.

New processes and technologies must go hand in hand with new modes of consciousness. Therein lies the path to the creation of truly new images. This is what we, the Three-Person Animation Circle, want to achieve through animation.

We have come together from separate disciplines — painting, cartooning, and design — not to create just another popular cross-media collaboration, but to transcend our own personal boundaries, to add a new dimension to our interactions by exploring different processes and modes of consciousness. For animation to evolve and stay truly contemporary, there is a need for much bolder and more varied experimentation, such as those we see today in the fields of live-action film, painting, and design.

We, the Three-Person Animation Circle, will always question convention and stand firmly on the side of innovation. (Kuri Yoji, Manabe Hiroshi, Yanagihara Ryohei)[9]

Much like Ōshima and Matsumoto, Kuri and his co-conspirators armed themselves with pen and paper in an effort to emancipate their medium from overbearing formal precedents. The need for animation “to evolve” through “new processes and technologies,” lest the craft prove “unable to break free of established thought patterns and methods,” echoes Ōshima’s berating of uninspired studio “program pictures”[10] and Matsumoto’s diatribes against overly-naturalistic documentarians.[11] Also akin to their counterparts working in live-action cinema, Kuri, Manabe, and Yanagihara experimented with various technologies, aesthetic modes, and narrative structures out of a belief that new stories and messages could only effectively be conveyed via revolutionary filmic techniques. In their eyes, such a creative process required the combination of forces by artists from disparate artistic “genres” (jyanru) who stand steadfast on the side of “innovation” (henkaku). While the careers of Manabe and Yanagihara would gradually veer off back toward illustrating and ad design (respectively) by the end of the decade, Kuri remained committed to the transformation of animated media, elaborating on the Animēshon sannin no kai mission statement in the pages of Kinema junpō in May 1963.

Kuri’s article, “Animēshon no mugen no sekai” (“The Limitless World of Animation”), serves not only as a primer to the first few iterations of the Animēshon sannin no kai festivals at the Sōgetsu Art Center, but also as a rough outline of Kuri’s own theory of animation. In the first subsection, “Shi no buttai wo sei no buttai ni” (lit., “From Dead Objects to Live Objects”), Kuri compares animation to an earthly god (kono sekai no kamisama), arguing that the medium uniquely enables still, lifeless objects to be brought to life through the illusion of movement.[12] Kuri contends that animators who continue to operate in the pre-war style of illustrated, Disney-like manga eiga forsake the limitless, celestial potential of animation and fail to express any kind of modern realism (rearusei). Kuri explicitly condemns the “childish,” labor intensive brand of animation practiced at studio Tōei Dōga (treated in this paper’s next section), celebrating instead the innovations of Canadian animator Norman McLaren. As a result, Kuri spends much of his first two subsections linking the rising interest in animation and economic opportunities for animators in Japan to the emergence of television and the flourishing design industry. He then proceeds to spotlight a few of his most recent formal experiments in a subsection entitled “Genzai no jikkenkadai wa mittsu” (lit., “Three Current Experimental Subjects”).

Kiseki (1963, Traces, 35mm, 5 min, Color) is twice referenced as a noteworthy examination of both color (shikisai) and space (kūkan).[13] In Kiseki, colorful squiggles, effervescent circles, and silhouetted specters wriggle and dart across the screen in synch with a jazzy soundtrack. In clear reference to Oskar Fischinger’s works of “visual music,” two-dimensional lines appear animate, as if able to dance. Meanwhile, three-dimensional circles – which Kuri refers to as “pendulums” (penjyuramu) – hypnotize the viewer with their vivacious colors while simultaneously drawing attention to the limitless depths of the otherwise flat, black onscreen space. This aestheticized, multi-medial exploration of animated space speaks to Kuri’s interests in how non-naturalistic uses of color might impact a spectator’s viewing experience, in addition to his belief that three-dimensional depth is underutilized in more traditional modes of animation.

The same subsection of Kuri’s article contains a brief treatment of Isu (1963, Chair, 35mm, 10 min, B&W), a work of pixilation which takes as its subject humans of various “occupations” (syokugyō) placed in a room – empty but for a single chair – while a live-action camera intermittently captures roughly fifteen seconds of footage over fifteen minutes. Employing an irregular time-lapse effect in a sparse, intimate space transforms mundane human movement into something remarkably uncanny and comedic. Kuri cites silent-era slapstick films, such as those by Charlie Chaplin, as his inspiration for the project, and suggests that animation constructed by means of the afterimage (sanzō ni yoru animēshon) remains underexplored but is soon to reappear in comedic cinema.[14]

“Ongaku to animēshon” (“Music and Animation”), Kuri’s penultimate subsection, proves to be his most polemic: not only does Kuri defend his practice of animating after acquiring or composing a soundtrack by stating, “music accounts for 80% of the effect of animation,” but he also wryly remarks that those weak in mathematics – and thus unable to calculate the progression of their images in synchronicity with music – have no business working in animation.[15] The meticulousness of Kuri’s production processes appears at odds with his larger project of liberating animation from restrictive formal inheritances. Kuri effectively works to dispel unspoken visual regulations while erecting new ones with regard to the relationship between the image track and the soundtrack. This contradiction constitutes one aspect of his work that varies substantially from the practices of New Wave filmmakers, who famously made use of recent advances in handheld camera technologies to break out of artificial studio sets in favor of more spontaneous and exploratory modes of filmmaking enabled by location shooting. However, one might ease this tension to a degree by calling attention to Kuri’s rather unconventional use of “music.”

Consider Nihiki no sanma (1961, Two Mackerel, 16mm, 20 min, B&W), Kuri’s first independently produced animated film, based on his 1959 manga collection by the same name. Many aspects of Nihiki no sanma would rarely, if ever, resurface in Kuri’s subsequent work, including voiceover narration, linear narrative, as well as sheer duration: Kuri almost immediately began to prefer making five- and ten-minute films. Nihiki no sanma can be loosely interpreted as an allegory of Japanese urbanization. The film begins with a man and woman arriving on a small island and establishing a tranquil, two-person agrarian society. A cheerful rising sun blows a trumpet in the background until a mustachioed man arrives and installs a large, anthropomorphized machine onto the island, unleashing a cacophony of mechanized sounds. For much of the film, the island’s original two inhabitants retreat to ever-smaller shelters as industrialization and overpopulation transform their oasis into a concrete jungle replete with clamorous automobiles and construction cranes. City folk first busy themselves and then arm themselves: as skyscraping housing developments literally break through the clouds, the island’s inhabitants are alerted to the approach of larger and larger bombs. The arrival of Armageddon brings the film to a screeching halt. The island is no more. The man and the woman somehow survive, their house teetering on wooden stilts in the open ocean. The perils of high-speed economic growth play out via a disharmonious soundtrack composed of buzzes, crashes, rattles, and roars. “Music,” in this case, is comprised of all manners of commotion, relating thematically to the image but not always in harmony with it. It would be this aspect of Nihiki no sanma – noise as music – that would be carried over into many of Kuri’s subsequent films.

In his concluding subsection, Kuri provides a synopsis of the first few years of activities by the Animēshon sannin no kai, listing out films exhibited at each of their three animation festivals and spotlighting the work of their recent guest, Carlos Marchiori, a renowned animator from Canada. The piece then proceeds to advertise the group’s next animation festival at the Sōgetsu Art Center (Kuri is, after all, an ad man by trade). Missing from these closing remarks, though, is any mention of what is arguably the thematic crux of both Kuri’s oeuvre and much of New Wave cinema: sexuality. Absent from the text but aired out continuously in his independent films, Kuri is clearly interested in adult animation.

It would be Kuri’s more erotically charged works that amassed accolades at international film festivals, including Ningen dōbutsuen (1962, Human Zoo, 35mm, 3 min, Color), Ai (1963, Love, 35mm, 5 min, Color), Aosu (1964, AOS, 35mm, 10 min, B&W), and Samurai (1965, 35mm, 8 min, B&W). These films frequently feature sexually frustrated miniature men fighting over oversized, nude, sexualized women. Urbanization parades as a violent crisis of masculinity, likely reflecting the skewed demographics of a Tokyo transformed by the postwar influx of young male migrant laborers.[16] These works also fulfill the criteria set forth by Ōshima in his aforementioned article: speedy, animalistic men engage in thrilling combat in search of sex. Scenes of half-pint men crawling inside of women, or gargantuan women devouring or enslaving their suitors, certainly shocked audiences who believed animation to be a medium for family fanfare. As these projects came to embody his signature style, Kuri experimented with more spontaneous soundtracks. In Aosu, for instance, the image track is set to a steady stream of sensual moans, groans, and wails recorded for the project by Yoko Ono.

How has Kuri’s impact on animated media in the early 1960s been omitted from discourses on the Japanese New Wave if issues of gender and sexuality shape the aesthetics and problematics of both his work and the period? One answer can be found by investigating “S’s” which Kuri operated outside of: the studio system.

Experimentation from “Within”? Two Early Short Films from Tōei Dōga

Looming large over the films and filmmakers often considered to typify the Japanese New Wave is the crucial role played by the studio system. Complicating the extent to which such films proved wholly avant-garde or anti-establishment, even the period’s poster child, Ōshima, made several of his most emblematic films as a studio director. Both Seishun zankoku monogatari (1960, Cruel Story of Youth) and Nihon no yoru to kiri (1960, Night and Fog in Japan) were bankrolled by Shōchiku. Though Ōshima purportedly cut ties with the studio over a dispute regarding the release of the latter project, he would continue to rely on Shōchiku to distribute many of his subsequent films.[17] Prominent filmmakers Yoshida Kijū and Shinoda Masahiro both spent the first half of the 1960s directing for Shōchiku. Beyond Shōchiku, several key figures at Nikkatsu, such as Kuruhara Koreyoshi and Imamura Shōhei, directed films that would later be heralded as exemplary works of the New Wave. Arguably, Suzuki Seijun’s notoriety hinged upon his tumultuous relationship with Nikkatsu, especially after his termination in 1967 over the film Koroshi no rakuin (Branded to Kill).

Seemingly in contrast to such a narrative is the formation of the Art Theatre Guild (ATG) in November 1961, a distribution company which would later (from 1967) go on to co-produce low-budget projects (“ten million yen movies”) successfully pitched to the ATG’s committee of critics and artists by filmmakers including Shinoda and Matsumoto. However, of ATG’s ten cinema houses, Tōhō Studios contributed five, in addition to a substantial amount of the guild’s initial funding.[18] As Roland Domenig argues in his brief history of the Art Theatre Guild:

[E]ven the Art Theatre Guild was dependent on Tōhō, its main financer and one of its initiators. ATG did not compete with Tōhō and the other studios, but they rather complemented each other. Experiments made possible by ATG were unthinkable within the structure of the studio system, especially in times of dwindling attendance and decreasing revenue. The studios preferred to let others worry about the unprofitable auteur films and concentrate instead on the rather more lucrative genre cinema. To a certain extent, however, the studios supported independent productions such as ATG’s because their experiments were considered an important source of innovation. From 1968 onwards, ATG became the major experimental laboratory of Japanese film.[19]

Thus, leaving a studio rarely translated into a departure from the larger studio system: many “independently produced” films from the late 1960s still benefited from economic support traceable to one of the major studios during the production and/or distribution process. For these reasons, the Japanese New Wave must be understood as a period of aesthetic and narrative experimentation within a dominant, albeit rapidly decaying studio system.

Kuri and his fellow Animēshon sannin no kai collaborators earned their livelihood almost entirely outside of this system. Kuri’s self-run studio generated revenue from illustration work and advertisements animated for television, and in the 1960s his erotic, experimental, independently produced films rarely screened outside of Animēshon sannin no kai events or international film festivals. However, during the same period, innovative animators could be found within the studio system – almost all of them, in fact, at a single studio.

In 1956, Tōei Company purchased a small animation studio, Nihon Dōga Eiga, forming Tōei Dōga Company, Ltd. Tōei’s intention behind the acquisition was to found an arm of the studio that could churn out one high-profile animated feature per year with an aesthetic that would emulate and rival the kind of “full animation” practiced in America by Walt Disney Studios: this look demanded 18 to 24 unique, full-color frames per second of film. Such labor intensive, expensive animated films were unprecedented in Japan at the time, and thus have been extensively covered in historical accounts of the period. However, little work has been done on animated shorts created at Tōei Dōga in the late 1950s, and it is within these films that one might locate the failed beginnings of an animated New Wave.

Ōtsuka Yasuo began working as an animator at Tōei Dōga soon after its founding, and recounts that in its earliest years the studio faced an unusual structural issue. The “single crop problem” (ichi mō saku), as Ōtsuka describes it, was the result of Tōei’s initial mission to have the studio create one feature film per year.[20] The studio’s aesthetic required a Taylorist production model, with each stage of the production process divided into small tasks handled by a worker with a narrow job description (e.g., cel colorist or animation “in-betweener”). With only one “crop” per year, many animators – especially those with more creative or managerial positions – would experience long periods of time at their desk and on payroll without a task to fulfill. During this time, studio heads would ask animators to form small groups and create animated shorts, sometimes on stories and in styles entirely of the animators’ choosing. Several animators working at Tōei Dōga during its inaugural years fondly recall this dream-like situation.[21]

Mori Yasuji, an experienced animator carried over from Nihon Dōga Eiga in 1956, was tasked during his first year at Tōei Dōga with creating an imaginative short film that could serve as a recruitment tool for the studio as it geared up for the production of its first feature, Hakujaden (1958, Tale of the White Serpent). As chief animator and conceptual artist, Mori worked with director Yabushita Taiji to produce Tōei Dōga’s first animated short, Koneko no rakugaki (1957, Kitty’s Graffiti, 13 min, B&W).[22] In a brief interview for Sugiyama Taku’s colossal, two-volume study of the first twenty years of Tōei Dōga’s films, Tōei Dōga chōhen anime daizenshū, Mori described the production process of Kitty’s Graffiti as “free and uncontrolled” (jiyūhonpon).[23] Equipped with considerable creative license, Mori and his team crafted a truly visionary product, incorporating a number of unusual aesthetic modes and playful cinematic self-reflexivity.

Dressed in overalls and armed with an enchanted pencil, the eponymous kitten in Kitty’s Graffiti begins by scribbling forth a number of animals and vehicles that spring to life soon after taking form. Though the film is made entirely in black and white, the kitten and other objects in the foreground are visibly animated by means of a cel-based process, whereas the titular graffiti on the white background is hand-drawn, sketchy by comparison, yet also animate. The harmony between these two worlds and two technologies is soon thrown off kilter when two mischievous mice steal the pencil and inadvertently unleash narrative and aesthetic chaos. The kitten’s quest to restore order requires the traversal of various aesthetic realms, generating a variety of self-reflexive jokes in a vein similar to that of Warner Bros’ Duck Amuck (1953). Mori’s project, however, takes the experiment one step further by blending various material media. By 1955, Japanese television owners could already tune into American animated series such as Superman, Popeye, Huckleberry Hound, and The Flintstones[24]; cinemagoers in Tokyo already had access to Peter Pan, Fantasia, Lady and the Tramp, and Toot, Whistle, Plunk and Boom.[25] Mori, clearly conscious of trends in American animation aesthetics, created for Tōei Dōga a pragmatic calling card. With its formal seams thoroughly exposed, Kitty’s Graffiti explores a juncture somewhere between full and limited animation, in dialogue with both Disney- and UPA-like modes of production.

A number of structural changes at Tōei Dōga in the years immediately following the creation of Kitty’s Graffiti resulted in swiftly worsening working conditions for the studio’s animators. Executives remedied the “single crop problem” by making salaried animators available to complete subcontracted labor for television or foreign productions.[26] Tōei Dōga began hiring inexperienced animators as poorly paid “trainees” and tasking more senior animators with their training during and between projects.[27] Starting salaries decreased while working hours and daily production quotes increased. Animators increasingly found themselves asked to work “un-creatively,” as Tze-Yue G. Hu describes, in accordance with stricter production guidelines and increasingly homogenized aesthetics.[28] In a later interview, animator Rintarō described his decision to leave Tōei Dōga only a few years after joining as a direct result of the oppressive work environment.[29]

A close look at Mori’s unofficial (and only) sequel to Kitty’s Graffiti, Koneko no sutajio (1959, Kitty’s Studio, 16 min, Color), reveals some of the regrettable consequences of this sudden shift in labor conditions. Though credited as director this time around, Mori’s blurb on Kitty’s Studio in Sugiyama’s study suggests that he enjoyed far fewer creative liberties. Though he originally planned to make a film about a kitten and its trumpet, he was asked to drop the project and make a story about a studio instead. [30] As with Kitty’s Graffiti, Mori proceeded to design Kitty’s Studio as a film without dialogue or narration, only to be ordered late in the production process to make his characters talk. Mori had access to greater resources, allowing Kitty’s Studio to be made in color; however, the visual style needed to be uniform. The film displays little in the way of formal experiment, but what lies beneath the surface is a biting critique of the studio-based production process.

In the short, the kitten finds itself tasked with making a Japanese period film on a studio set, without a crew and with shoddy equipment. The two mice again appear, this time as katana-wielding, rather untalented actors. As the kitten directs them in a duel, it must also crank the film camera and simultaneously operate a defective vinyl record player. These opening minutes provide glimpses of what Mori might have envisioned for Kitty’s Trumpet, a project that would never be realized: when the record slips into a loop, the mice suddenly find themselves stuck in a continuously repeating jump cut, one of the few instances of diegetic rupture. When the film camera goes kaput and the film stock unravels, the discouraged kitten decides to create an “automation studio.”

In the new studio, robots reign supreme. The inadequate mice are encaged and replaced with skilled mechanical doppelgangers. Automated, state-of-the-art equipment enables filming to proceed without a hitch until the two downtrodden rodents begin to crack the façade of technical perfection, first by disrupting the music box, and then by manufacturing an army of mutinous automatons. All three animals struggle to regain control over the situation, but remain unsuccessful until the kitten decides to construct its own robotic replica. The robot director restores order to the studio, and the kitten sees an opportunity to escape its working conditions. With the final words of the film – “I leave this up to you, bye bye!” (kimi ni makaseyō, bai bai) – the kitten entrusts the production to the robot director and takes its exit alongside the two mice.

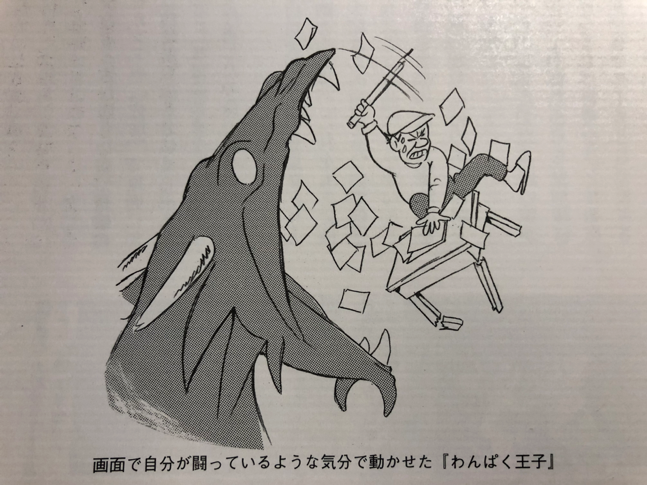

Events at Tōei Dōga in the two years following the release of Kitty’s Studio would play out much the same. In his memoirs, Mori describes his coworkers as afflicted with “anime syndrome” (anime shōkōgun), a combination of malnutrition and fatigue that led many to be hospitalized, including director Yabushita Taiji during the production of Tōei Dōga’s 1960 feature film Saiyūki (Journey to the West).[31] The labor dispute escalated in 1961, with animators staging strikes and the studio responding with a multi-day, full-scale lockout.[32] Though negotiations restored a semblance of order in December 1961, a slew of skilled animators left to pursue work outside of the industry or at small studios, including the operation Tezuka Osamu was forming for the creation of the Tetsuwan Atomu (Astro Boy) television series. Those who stayed assert a marked downturn in picture quality and originality after the strikes. Ōtsuka, who remained at Tōei Dōga until the end of the 1960s, opens his chapter on the decade with a telling sketch from the production of Wanpaku ōji no orochi taiji (1963, lit., “The Naughty Prince’s Serpent Slaying). The illustration is subtitled, “Made to work with the feeling that I am embattled.”[33]

In Search of a “New Wind”

During the late 1950s and 1960s, when a number of live-action directors were devising formally and narratively disruptive films that would shape an entire period of Japanese film history, innovation in the art of animation developed in Japan on two fronts. In one case, a burgeoning domestic television industry generated a steady demand for animated commercials, whereby aspiring animators could establish small, predominantly self-run studios for the production of both advertisements and short, independent animated works. In the vanguard of this movement can be found Kuri Yōji, Manabe Hiroshi, and Yanagihara Ryōhei, founding members of the Animēshon sannin no kai and the pioneers behind a new festival exclusively for independent animation, regularly held under the group’s name at Tokyo’s Sōgetsu Art Center. On another front, animators of the likes of Mori Yasuji worked at the industrially groundbreaking studio Tōei Dōga to flex their creative muscles, only to soon find themselves toiling away on colossal features and subcontracted projects that demanded strict observance to pre-established timelines and pre-determined visual styles.

Studied collectively, these two fronts do not amount to an animated New Wave. Whereas New Wave directors largely experimented from within – or from the fringes of – the Japanese studio system, animators at Tōei Dōga experienced a stifling of their creative impulses. This curtailing of formal experimentation by rapidly deteriorating studio labor conditions in the late 1950s is laid bare by the stark differences between projects such as Kitty’s Graffiti and Kitty’s Studio. New Wave directors gained access to handheld cameras, began location shooting, and experimented with editing and production techniques that lessened the cost and person-hours required for the creation of a film. Meanwhile, the Taylorist production processes employed at Tōei Dōga suppressed aesthetic flare at the level of the individual. Furthermore, Kuri’s writings betray his belief that he was working in opposition to modes of animation championed by film studios, especially Tōei Dōga.[34] However, by working outside of and against the studio system, Kuri and his collaborators found themselves economically bound to their design and TV advertisement work. When Kuri did find the time and resources to experiment with animation, his audience was severely restricted: his films were too explicit to be aired on television, and too low budget to be distributed commercially. The extent to which he could aesthetically trail blaze was limited to the visibility he could achieve through international film festivals, cinema journals, and intermittent programs at the Sōgetsu Art Center. Nevertheless, the many commonalities between Kuri’s independent works of animation and Japanese New Wave cinema, including formal and aesthetic experimentation, the proclivity to shock the audience rather than to please them, and the thematic “S’s” (speed, thrills, and sex), hint at the rumblings of a movement not too dissimilar to the New Wave.

The two final paragraphs of Kuri’s Kinema junpō article read as if an artistic call to arms:

From now on, animation will advance strongly with regards to television. I also find research on made-for-TV animation to be indispensable, in order to deliver forth a new style (shinpū, lit., “new wind”) into the world of Japanese television, heretofore monopolized by American cartoons (Amerika manga).

The future of animation is limitless, and so I hope that manga artists, designers, and painters will advance in these directions with greater passion. For them, the Animēshon sannin no kai will serve as pioneers (kaitakusha) rather than top stars (toppu sutaa).[35]

Integral to Kuri’s vision for the future of animation is intermediality: not only will the medium flourish via experimentation within the television industry and without of the studio system, but it will also be transformed by the visions of manga artists, painters, and illustrators, by the sounds of musicians and performance artists, and by the business acumen of graphic designers and advertisers.

To an extent, Kuri’s mission mirrors those pursued by New Wave filmmakers, but could be better described by adapting his own verbiage in his call for a “New Wind” to blow through Japanese media. Swooping in to lead an aesthetic revolution staged over airwaves, Kuri recognized the restrictive labor conditions placed on animators by the studio system, and resisted by leveraging the collective talents of experimental artists from a wide range of media industries. Future studies could benefit from looking further into and around the projects initiated by the Animēshon sannin no kai through connections forged at both domestic and international film festivals. From there, writing a history of Japanese New Wind media would require one to move beyond the framework erected by scholars of New Wave cinema in search of artistic trends rooted firmly in sites of intermedial collaboration.

Jason Cody Douglass is a Ph.D. student in Yale University’s combined program in Film and Media Studies and East Asian Languages and Literatures, as well as the graduate program in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies. His research interests include animation, film and media theory, and East Asian cinema. Most recently, he contributed a chapter on early Japanese TV commercials to Animation and Advertising (eds. Kirsten Moana Thompson and Malcolm Cook). In the fall of 2019, he will be teaching a course on animation history at Sarah Lawrence College.

References

[1] Kuri Yōji, “Animēshon no mugen no sekai,” Kinema Junpō no. 339 (May 1963), p. 69. Author’s translation.

[2] Ōshima Nagisa, “Is It a Breakthrough? (The Modernists of Japanese Film),” Cinema, Censorship, and the State: The Writings of Nagisa Oshima, ed. Annette Michelson (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1992), p. 26.

[3] Ibid., p. 33.

[4] Ibid., p. 31.

[5] Kuri Yōji’s personal website, accessed 6 December 2017 (http://www.yojikuri.jp/bio_yojikuri.html).

[6] Ibid.

[7] Personal communications with Kuri Yōji, 7 December 2017.

[8] Kuri, “Animēshon no mugen no sekai,” p. 70.

[9] Kuri Yoji, Manabe Hiroshi, and Yanagihara Ryōhei, “Atarashii imēji wo saguridasu tame ni – animēshon sannin no kai no manifuesuto,” Sōgetsu Aato Sentaa Panfuretto no. 7 (October 1960). Translation by Colin Smith (Museum of Modern Art Website), accessed 6 December 2017 (http://post.at.moma.org/sources/3/publications/72).

[10] See, for instance, Ōshima Nagisa, “To Critics, Mainly – From Future Artists” Cinema, Censorship, and the State: The Writings of Nagisa Oshima, ed. Annette Michelson (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993), pp. 21-25.

[11] See, for instance, Matsumoto Toshio, “Sakka no shutai to iu koto,” Nihon kiroku eiga sakka kyokai kaiho (December 1957).

[12] Kuri, “Animēshon no mugen no sekai,” p. 67.

[13] Ibid., p. 69.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Oguma Eiji, “Japan’s 1968: A Collective Reaction to Rapid Economic Growth in an Age of Turmoil,” trans. Nick Kapur with Samuel Malissa and Stephen Poland, The Asia-Pacific Journal vol. 13 iss. 11 no. 1 (March 2015), p. 7.

[17] Roland Domenig, “A Brief History of Independent Cinema in Japan and the Role of the Art Theatre Guild” (Japan Society Website), accessed 10 November 2017 (https://www.japansociety.org/resources/content/2/9/5/6/documents/History%20of%20ATG%20by%20Roland.pdf).

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ōtsuka Yasuo, Sakuga asemamire (Tokyo: Tokuma Shoten, 2001), pp. 60-61.

[21] Jonathan Clements, Anime: A History (London: BFI Palgrave, 2013), pp. 100-102.

[22] Tsugata Nobuyuki, Nihon animēshon no chikara: 85-nen no rekishi o tsuranuku futatsu no jiku (Tokyo: NTT Shuppan, 2004), p. 132.

[23] Sugiyama Taku, Tōei Dōga chōhen anime daizenshū (jōkan) (Tōkyō: Tokuma Shoten, 1978), p. 75.

[24] Jonathan Clements and Motoko Tamamuro, The Dorama Encyclopedia: A Guide to Japanese TV Drama since 1953 (Berkeley, CA: Stone Bridge Press, 2003), p. xv.

[25] Clements, Anime: A History, p. 83.

[26] Ibid., 101.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Tze-Yue G. Hu, Frames of Anime: Culture and Image-Building (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2010), p. 139.

[29] Rintarō = Rintaro: kōsei henshū Sutajio Yū (Tokyo: Kinema Junpōsha, 2009), pp. 30-31.

[30] Sugiyama Taku, Tōei Dōga chōhen anime daizenshū (jōkan), p. 78.

[31] Clements, Anime: A History, p. 103.

[32] Ibid., 104.

[33] Ōtsuka, Sakuga asemamire, p. 69.

[34] Kuri, “Animēshon no mugen no sekai,” p. 67.

[35] Ibid., p. 70. Author’s translation.

© Jason Douglass

Edited by Amy Ratelle