Introduction

“Tradigital Mythmaking” might seem to be an unusual venture at first—a German animator and animation scholar working with young Asian artists to create new concepts for animation that are based on Asian mythologies and artistic traditions. An excursion into my own artistic and research background will establish the project in a wider context and explain its motivation. My own past and ongoing work has largely been defined by the search for a very personal and genuinely German style of animation. I came to Singapore in 2005 to teach animation at the new School of Art, Design and Media at Nanyang Technological University. The multi-cultural society of Singapore offers a beautiful kaleidoscope of the rich traditions of the regional arts—of course, prominently Chinese art, but also Indian, Malay, Indonesian and Philippine art-styles. I found that this wonderful diversity was not yet reflected in animation. My local students seemed to look primarily elsewhere for inspiration: they were mainly influenced by manga and anime and also tended to copy the design style of the Hollywood feature animation as established by Pixar, Dreamworks and Blue Sky Studios.

My initial impressions and findings were supported by scholarly research in the field. According to Engel (2009), “Very often, there is a reliance on derivative concepts in character design and storytelling. The Japanese anime-style and the American school of caricatured realism are used as templates to ensure commercial success. While the commercial prospects of such an approach are questionable, it obviously prevents full artistic success. Originality and innovation are missing” (p. 5). Other scholars such as Hodgkinson (2009) agree that “This is a common problem with much Asian animation, where the computer 3D style, along with the Japan’s anime aesthetic, dominates animation thinking and production. Many traditional Asian stories lose artistic connection with the story’s roots and relevance” (p.1).

Fairy-tales, folk-tales, and legends have always been a prime source of story material for animation. In particular, the titles of Walt Disney’s feature films read like the canon of European fairy-tales (Snow White, 1937; Cinderella, 1950; Sleeping Beauty, 1959). In addition, numerous Asian mythologies have served as inspiration for Western filmmakers and writers. In 1927, Lotte Reiniger created the world’s first animated feature film with The Adventures of Prince Achmed (ASIFA, 2007), which was based on the Arabic Tales of 1001 Nights, in a style heavily influenced by oriental art (ASIFA, 2007). In addition, a collection of Malaysian legends inspired Rudyard Kipling to write his Jungle Book (Muthalib, 2009).

However, in the region of Southeast Asia itself, the adaptation of such source material as an inspiration for animation is still in its infancy, and has yet to achieve convincing results. Academic explorations of the subject matter are extremely rare. The renowned Malay animation scholar, Hassan Muthalib, concludes that “So far, only literary writers and researchers have forwarded suggestions for the preservation of the nation’s folktales, legends and mythologies through feature films but nothing has materialized in a big way” (Criticine, [online]).

Regarding the film King Vikram and Betaan the Vampire (2004) by director Sutape Tunnirut, the British film journalist, Robert Williamson, observed, “The film combines a well-known local legend with a contemporary in-joke humour learned from American films such as Shrek. Although the combination is generally successful, it highlights a problem inherent in the development of Southeast Asian animation: how to differentiate local animation from Hollywood and Japan while still appealing to audiences who love Disney and Doraemon”. He further elaborates on the general state of the art form in Southeast Asia:

Moreover, it is noticeable that, observing that the Philippines animation industry achieved a step up by employing western talent, many in Singapore and Malaysia are resigned to bringing in Western filmmakers (such as Sing To The Dawn by director Frank Saperstein) to lend weight to their shaky, fledgling industries. This may boost confidence in the industries, but reveals the lack of direction and impetus locally. Southeast Asian animation is still a long way from finding its own identity. (Williamson, 2005)

Overview of the history and current state of animation in Southeast Asia

This phenomenon must be contextualized within the larger background and history of animation in the Southeast Asian region. The major countries linked to animation production are Malaysia, Singapore, the Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand, and Vietnam. (Muthalib, Cheong, and Wong, 2002) While each of these countries certainly has its own animation history that is closely linked to different cultural influences and political developments (the very specific case of Vietnam is a significant example), there are notable similarities between them, including the following:

• The strong influence of foreign countries (colonial-and post-colonial eras in the 1950s and 1960s accompanied the first local attempts in animation).

• The development of local animation production was closely connected to political developments (e.g., the Vietnam War and the Marcos dictatorship in the Philippines).

• Story sources were local fairy-tales, stories and legends.

• Animation was frequently produced in styles modelled on Western styles (e.g., Disney/Warner Brothers cartoons), with some notable exceptions.

• Since the 1980s, outsourced work from America and Europe has become a main driving factor in Southeast Asian animation industries.

• The digital revolution of the 1990s and 2000s enabled cheaper global production and brings recognition of animation as a medium with strong economic potential.

• Government funding and improved education have supported the local animation industry since 2000 in several countries, most notably Malaysia (Mahamood, 2001) and Singapore (e.g., Media 2001 Initiative and the Media Development Authority) (Muthalib, 2010; Media 21, 2003).

The acknowledgement of the importance of animation as an art form has led to encouraging signs. For example, shorts such as Singapore Overrun by Swordfish (Alan Aziz, Malaysia/Poland, 2000) feature a fresh and innovative design style and were strongly inspired by local art traditions. Swordfish uses a traditional story as the inspiration for poetic innovation using local design styles. Alan Aziz studied animation in Poland but came back to Malaysia to develop a local story for his Singapura Dilanggar Todak (Singapore Overrun by Swordfish, 2000). The story was based on the well-known legend of a fishing village and how a boy saved the villagers from swordfish. It was manually animated but finished digitally. Tan Jin Ho’s 3D film, A Malaysian Friday (2001), about a lonely paddy planter, became the rave of the industry and won many awards (Muthalib, 2007).

Also outstanding is the feature film, Khan Kluay (Thailand, 2006), (Internet movie database [online]) combining state-of-the-art digital animation with local design flavour and a story based on a traditional legend. Despite its successes in visual design, its shortcomings in storytelling and animation quality have been criticized. (ThaiCinema.org [online]) In Malaysia, feature film projects such as the Geng (2009) (Internet movie database [online]) and Alamaya (work in progress) have started to acknowledge the richness of the local cultural heritage and scenery in their designs while still struggling with similar shortcomings, particularly in dramaturgic quality and visual storytelling (Ians [online]). In Singapore, local animation film-makers such as Srinivas Bhakta have created shorts inspired by their own cultural heritage, winning awards in international animation film-festivals (Bhakta, 2009). However, these examples stand as notable exceptions in a dominant trend that favours a more generic approach guided by the often unfulfilled expectations of commercial success by using Westernized concepts.

Tradigital Mythmaking-the research project

Research problem and hypotheses

Forming a unique individual artistic identity is a crucial goal for most artists, specifically for the young and developing artist. Uniqueness has also become almost necessary for success in an increasingly competitive and globally interconnected artistic environment. This precondition is particularly true in the competition among animation creators of short films and TV series as opposed to hired artists in a studio environment. A young artist might find inspiration for his artistic development in his own cultural roots, which also link him/her to the greater artistic and cultural identity shared with other artists in his cultural environment (country, region, or community). The big advantage of this approach lies in its implied genuine and authentic foundation for artistic development. Ideally, these inspirations will evolve in combination with the artist’s own personality into a visual style that reflects both his/her cultural background and expresses a personal vision in a unique and innovative way.

The initial inspiration for this approach to animation originated from the author’s background as an independent animation film director in Germany. To avoid copying the dominating “Disney-style” of animation, I examined genuinely German art styles like the expressionism of the early twentieth century along with pioneering German animators like Lotte Reiniger (Wegenast, 2010), while studying animation at the State Academy of the Arts in Stuttgart. German art academies in general served as foundations of a true renaissance of highly artistic animation in more innovative and genuinely German styles throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Since my arrival from Germany in Singapore in 2005 to become an Assistant Professor for animation at the then newly-founded School of Art, Design and Media at Nanyang Technological University, my own exploration of the subject matter and findings such as the above have defined and informed his research interest.

Ulrich Wegenast, director of the Festival of Animated Film Stuttgart, says about contemporary German animation that it is“Abstract, opulent, witty, subversive and always with great depth and full of brilliant images—German artistic animated film is characterised by an extremely high artistic quality; a quality which has made it so successful at festivals, both at home and abroad. A unique compendium of contemporary animated culture” (2010 [online]).

One could further argue the strong need for a reconnection with indigenous cultures because the younger generation is often estranged from the more traditional aspects of their own cultural environment. I have experienced the perplexity of local artists who, witnessing the admiration of their native artistic tradition through a stranger’s eyes, asked the rather un-academic question, “Why do you like Chinese painting so much?” Thus, the idea was born to reconnect Asian animation students in Singapore to their cultural roots as a source for developing stories and art for animation and was the impetus for the research project, “Tradigital Mythmaking-Singaporean Animation for the 21st Century” (Rall, 2006-2008; Rall, 2010-2012), which was started by me as principal investigator (PI) in 2006 and is in progress.

Research methodology

The research started with the analysis of Asian mythologies in their cultural and historical contexts and how they had been visualized throughout history. The research team investigated the mythological and art history traditions of China, India, Thailand, Malaysia, Vietnam, the Philippines and Singapore. The research also examined contemporary trends and approaches to illustrating and adapting mythology and folk stories for various media. From the wide selection of mythological Asian stories available a sample was chosen, by applying criteria for their suitability as animated adaptations according to the following questions:

–Are there major components of the story that could only be realised when using the medium of animation?

–Does the story hold a strong potential for a visually exciting adaptation?

–Can the story be adapted to the format of an animated short film, TV special or animated feature film?

–Does the story resonate with the artistic sensibilities and ambitions of the creators working on it?

Six stories were finally picked for further development into concepts for animated film. While the majority of them are rather faithful adaptations of original stories, others use mythology as a basis for a newly assembled narrative in a contemporary context (e.g., The Rice Goddess). The final selection included the following:

–The Beach Boy– animated short (Vietnam) (Binh, 1985)

–Juan– animated short (Philippines) (Cook, ed., 2000)

–Post Ramayana – feature (India) (Cornelius-Takahama, 1999)

–Two Sisters– animated short (Singapore)

–The Rice Goddess – feature (Indonesia)

–Ma Liang: The Boy with the Magic Paintbrush– animated short (China) (Ker, 2009)

Sixty student participants were divided into six research groups to work on these six animated concepts. Whenever possible participants who were nationals of the corresponding countries, assumed key development positions for each story. Additional research was undertaken on visual reference for the respective cultures and art traditions, including several field trips by the participating students. Each story was fully explored to the point of completed pre-production.

This development process started with the traditional process of script writing by adapting the source material or creating new stories using local topics and characters. Very often storyboarding and character design started simultaneously to flesh out the visuals and the staging of the stories. Great care was taken to develop the visual design in a way that carefully integrated local design elements and respected their aesthetic philosophy. At the same time, I encouraged experimentation to discover new artistic approaches. This philosophy was further carried out through prop and background design, colour mood-boards, production paintings, and colour script for each film.

We also explored different technical options to achieve the look(s) we were trying to accomplish through experimental animation and lighting and rendering tests. Finally, an animatic/Leica reel was created for each film concept for the evaluation of dramaturgy and pacing.

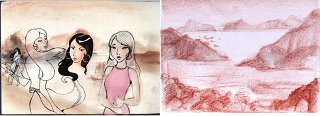

Fig. 1 – Development art from The Beach Boy: artists—Nguyen Hieu Hanh and Tran Ngoc Viet Tu

The artistic styles and animation techniques chosen for the projects reflect the inspiration by the research of genuinely Asian art traditions. The use of analogue and digital tools in the process was wholly informed by the artistic intention to re-create these styles in the animation medium. For the story, “The Beach Boy”, a style was developed that combined a muted colour palette with textured crayon backgrounds and a line style reminiscent of the calligraphic quality of traditional Chinese painting.

Fig. 2 – Development art from The Beach Boy: artists—Nguyen Hieu Hanh and Tran Ngoc Viet Tu

For the experimental animation of his concept, the newly developed 2D animation CACAni software (Qiu et al., 2005a) was used, which enabled inbetweening of key frames with a varied thickness of lines.

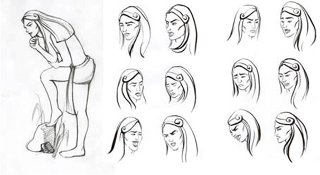

Fig. 3 – Character development studies for The Beach Boy: artists—Viet Tu/Cao Youfang

The research also explored a highly interesting proposition: if one assumes that authenticity forms an important part of developing an outstanding artistic vision, the definition of artistic authenticity in the context of multi-cultural and internationally highly connected countries such as Singapore is crucial. Singapore is a country in which a very strong presence and influence of Western culture co-exists with the cultural traditions of Asian communities. Thus, it might be rightfully argued that an authentic approach of a young artist in Singapore may be defined equally by Western and Asian influences. This hypothesis can also be generalized to a certain extent because the Internet has furthered the process of the global exchange of artistic statements. However, the multicultural influence on artistic production seems particularly appropriate for Singapore, where trans-cultural identification processes can be experienced not only in the virtual world but also in the very real world.

Because this question was repeatedly raised in the research process as well as in academic discussion with peers, the research project integrated this specific problem in the methodological approach and in self-reflective discourse with academic scholars. The investigator came to the conclusion that a “fusion of Asian and Western styles” used by young artists in the project is fully legitimate and serves the purpose of developing an innovative approach. It might further be argued that these combined influences even maximise the potential for originality and innovation. If we assume that innovation has often been achieved by the combination of formerly unconnected and unrelated areas, then that argument is further strengthened. Therefore, the methodological approach of the research was defined by offering young Asian artists the opportunity to re-connect with the artistic and narrative traditions of their respective culture groups. In many cases, this exploration came as an entirely new experience for the young animators and was strongly welcomed as a source for inspiration.

In the second step, the participating students were encouraged to combine their new found inspirations in ways that inevitably integrated their own artistic preferences, including Western styles. The key to this approach lies in the concept of enabling innovative artistic development by widening horizons and increasing stylistic options. This approach involves a concept very different from forcing an artistic dogma of “Asian authenticity” or “purism” (if such definitions can be applied) on artistic development. As the research supervisor I carefully applied only criteria of general artistic quality for evaluation of the development while avoiding any assessment based on cultural prejudice. If an artistically appealing and cohesive stylistic vision emerged, it could be as well defined by a trans-cultural artistic identity (Western-Asian fusion) as by a re-interpretation of a specific traditional Asian art style that stayed closer to the source material.

Three different examples from the research project provide further evidence and explanation for the legitimacy and methodology of this approach. First, The Rice Goddess was a concept for an animated feature film that originated from the comprehensive exploration of the rice culture in Bali, both in visual art and narrative traditions. One research assistant of Balinese origin undertook elaborate field trips in Bali, which resulted in a vast array of visual references consisting of drawn sketches, photographs, colour studies, and collections of local stories. The artists were particularly fascinated by the representation of the multiple supernatural beings in visual and oral traditions. The visual development concentrated on exploring character designs of this mythological universe while a story was developed that linked the mythology to the authentic Balinese rice culture.

Another strong source of inspiration was found in the traditional shadow puppet play, Wayang Kulit (Rawlings, 2003), which can also be found in aspects of Malaysian and Chinese culture. In almost exemplary fashion, the developmental artists identified typical design elements of the traditional art and combined them with their own artistic style.

Fig. 4 – The Rice Goddess – images from trailer: artist—Cheng Yu Chao

Second, The Boy with the Magic Brush was another concept for an animated short film that was based on a story of Chinese origin. Ma Liang and the Magic Brush (Pinyin: shen bi ma liang)—otherwise known as The Magic Brush (shen bi)—was penned no earlier than the middle of the twentieth century by Hong Xuntao (1928-2001), an author of children’s literature from Zhejiang province. The story concept centres on a magic brush, which brings everything to life that it paints. The idea inevitably led to an adaptation for animation, which was first executed by the legendary Shanghai Animation Film Studio for a stop-motion puppet animation in 1954. The animation went on to garner five awards at international festivals in Venice, Belgrade, Warsaw, Damascus, and Stratford in 1956 and 1957 (Ker, 2009).

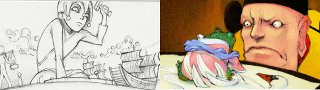

For the “Tradigital Mythmaking” project, a new adaptation was developed as a fascinating option based on the potential of the story for animation and its transfer to a different artistic style and animation technique. The visual and narrative development was led by Wang Xun, a Chinese national living in Singapore, and Huang Xin Hui, a Singaporean of Chinese heritage. Their artistic development of this adaptation strongly mirrors the specific Singaporean environment of unity in diversity as it displays the cultural mix of both Western and Asian artistic influences. Animation scholar Yin Ker states in her article about “Ma Liang”:

Admittedly, in this latest adaptation of The Magic Brush, “Chineseness” is no more than an assumption and a garnish that credits the Chinese origin of its story; this animation’s prioritas remains storytelling. It does not seem that the animators from Singapore are concerned with Chinese pictorial aesthetics either—an observation that is not made in reproach. In order to play up the dramatic potential of The Magic Brush, the China team has favoured a representational mode involving extensive foreshortening through panning, zooming, and other camera tricks, and this is not a way of picturing that is conventionally compatible with classical Chinese painting—although Chen’s Brush can prove this dichotomy irrelevant most elegantly. Besides, in making colour a chief player in this animation—not to mention endowing it with expressive qualities, the China team withdraws itself further away from the Chinese idiom. Although it would be farfetched to suggest that Chinese pictorial aesthetics disregards colour entirely, it is obvious that the role assigned to colour by Singapore’s China team cannot be satisfied by a pictorial aesthetics which employs hues and shades for significantly different purposes. Whether in terms of colour, texture or composition, it is clear that they have either looked away from the Chinese model, or succeeded little in assimilating it. (2009, p. 43)

The Chinese artists involved granted themselves the liberty to freely choose from a wide variety of artistic options, favouring a design that in their opinion most strongly supported the narrative and appealed to them with its dramatic visual impact.

Fig. 5 – “Ma Liang—The Boy with the Magic Brush”: development art by Huang Xin Hui

I approved this approach, as the key to this evaluation was the overall coherence of the artistic vision along with the aesthetic integrity of the designs in service of the story. In that sense, The Boy with the Magic Brush exemplifies the concept of an approach that originates from an inspiration by traditional Asian art but further develops by fusing Western and Asian approaches in its final design vision. The justification of the adaptation, fusion, and interpretation of art styles linked to specific culture areas and countries (e.g., Chinese painting) by foreigners is subject of an ongoing discussion in professional and academic circles. Most prominently, Disney’s adaptation of Mulan (Internet movie database [online]) led to some controversy (Weimin and Wenju, 2000).

Such discussions might just as well be motivated by ideological bias and political motivation as by purely artistic criteria. The author is inclined to think that any vision that respects important aspects of the original art sources, identifies the key design characteristics, and integrates them skilfully into a new artistic style should be considered legitimate as an artistic expression. In the case of Mulan. the production designer, Hans Bacher, researched and developed the art style for the film thoroughly with the greatest of respect for the culture from which it originated (Bacher, 2007).

The third example, Juan, was selected by the research group in charge of the Philippines as a suitable story for animation. This whimsical fairy-tale was the right length for adaptation as an animated short- film; it also provided great inspiration for visual development with vivid characters, magical creatures, and the fantastic jungle environment where the story takes place. However, it proved to be far more difficult to find the right visual style for the story. The researchers studied the art traditions of the Philippines very thoroughly, yet they failed to identify a strong visual style that also would match the contents and character descriptions.

The artistic traditions of the Philippines are more splintered and diverse than those of their neighbouring countries. It is very difficult to identify a very strong and unique local art style analogous to the tradition of Chinese painting in China and Vietnam or the Wayang Kulit in Malaysia and Indonesia (Guillermo, 1996). However, a clear tendency to favour strong and brilliant colours along with a noticeable influence of European art styles (due to Spanish colonization) can be identified as a common characteristic. These findings were integrated in the design approach that was finally taken.

Chua “Calvin” Tin Giap, a Malaysian student, created a cast of characters and a set of environments in a style which might be best described as “Tim Burton meets Henri Rousseau”. Calvin’s artistic personality is so strong that something entirely new emerged.

Fig. 6 – Juan, coloured animation still and image from trailer: artist—“Calvin” Chua Tin Giap

Because the Philippines have also continuously produced very talented artists, who have brought their skills to the creation of Western animation and comics (Ong Pang Kean, 2006) (Alex Nino, Alfredo Alcala and Nestor Redondocome to mind), Calvin’s approach seemed to be a very appropriate method. This variation is the third in the approach taken by the project. It is a faithful adaptation of a traditional story made contemporary by the use of a very personal and unique style.

Local art styles are used here as the starting point of an artistic voyage of discovery. The stylistic variety of the animation concepts in this research project mirrors the multi-ethnic diversity of Singapore. The outcomes also contribute in unconventional ways to the discussion of what defines the national identity of Singapore. They represent a kaleidoscope of cultural influences that co-exist peacefully in the country. One of the most interesting outcomes might be the finding that the formative years of young animation artists in Singapore and the surrounding countries in Southeast Asia are strongly informed by the mix of Western and Asian influences. These artists are now discovering or re-discovering their cultural heritage while integrating these influences in un-dogmatic ways with Western pop culture.

Final conclusions and outlook

These explorations might not always result in artistic success, but they provide evidence of the vital and prolific generation of young animation artists in Southeast Asia who are now coming into their own. The combination of the growing amount of high-quality education in regional tertiary institutions along with the raised awareness of the commercial and artistic potential of animation has resulted in the support of the national governments. This research project can be contextualized within this bigger trend, which will produce a multitude of new animated short films by Southeast Asian film makers emerging on the festival circuit in the near future. It distinguishes itself by the approach of solely applying criteria of artistic quality and research integrity without inhibiting creative development by making potential commercial success a requirement.

Strategies that imply the guarantee of economic success based on copying a perceived formula from Western or Japanese concepts have often proved to fail artistically as well as economically. The author strongly believes that the search for strong and unique artistic voices in Southeast Asian animation will ultimately result in a more sustainable success. Overall, the outlook is encouraging. The ongoing support by local governments for the art form has led to more educational institutions with high standards and a growing animation industry. New channels for funding animation projects have materialized. However, most importantly, this support leads to a whole new generation of well educated and aspiring animation artists expressing themselves in unique voices. They employ their high-level skills to create highly personal independent animated short films that reflect their heritage and environment. Tan Wei Keong (2009) and the brothers Harry and Henry Zhuang (2010)are just two examples. Their films have already been awarded in international animation festivals. The brothers Zhuang also plan to found their own production house after graduation. (Corporate Communications Office [online]). Such examples are also important because they demonstrate the beginning of a trend of young artists starting their own independent production companies, which will hopefully enable the production of innovative animation, and thus diversify the local palette of animation production and provide new inspiration to the mainstream.

In the context of these encouraging prospects, I have just embarked on a new research venture. “New Computer Animation Techniques for the Replication of Wayang Kulit” (Rall, 2011-2013) examines how the traditional art of shadow puppet play in the region can be preserved through state of the art of technology. By developing software with a simple and intuitive interface, we want to enable traditional artists to discover new artistic options. This research is a continuation and expansion of the initial research I undertook on “Wayang Kulit” in the “Tradigital Mythmaking” project. The local legend “Mount Faber”, about the creation of Singapore’s highest peak, will serve as the basis for the animation experiments. This interdisciplinary research is a joint project with colleagues from the English Literature and Computer Science faculties. Lotte Reiniger started a fascinating artistic journey inspired by Asian shadow puppet play a long time ago—a tradition I hope to continue in my very own way.

Born in Tuebingen in 1965, Hannes Rall graduated from the State Academy of the Arts Stuttgart in 1991 and after that was one of the first students at the Filmakademie Baden-Wuertemberg. Since then he has gone on to become an independent animation director, illustrator, educator and scholar. He is a renowned director of independent animated short films, with 8 major film-funding grants awarded to him by German and European institutions. His short films “The Raven“ (1999) and ”The Erl-King“(2003), adapted from the famous poems by E.A. Poe and J.W. von Goethe respectively, have been shown in over 100 film-festivals and won multiple awards. Currently Hannes is directing the 25 minute animated short-film “The Cold Heart” adapted from the novel by Wilhelm Hauff, funded by MFG Baden-Wuerttemberg for a 2012 release. Since 2005 he is an Assistant Professor at the School of Art, Design and Media at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore. In his research project “Tradigital Mythmaking-Singaporean Animation for the 21st Century” project Prof. Rall explores the development of genuinely Southeast Asian animation styles, which are not derived from Western or Japanese concepts.

This paper was presented at Animation Evolution, the 22nd Annual Society for Animation Studies Conference, Edinburgh July 2010.

References

ASIFA animation archive, 2007. [online]. Available at: http://www.animationarchive.org/2007/01/filmography-reinigers-prince-achmed.html [Accessed 10 September 2010]

Bacher, H., 2007. Dreamworlds—Production Design for Animation. Oxford/Burlington: Focal Press, 100-121.

Bhakta, S., 2009. My Father is a Washerman [Film] Singapore.

Binh, Nguyen Ngoc, 1985. The Power and Relevance of Vietnamese myths. Asia Society’s Vietnam: Essays on History, Culture, and Society, pages 61-77.

Chen, Q., Tian, F., Seah, H.S., Wu, Z.K., &Konstantin, M., 2006. DBSC-based Animation Enhanced with Feature and Motion. Computer Animation & Virtual Worlds, 17(3–4), 189-198.

Cook, M. C. ed., 2000. Adventures of Juan in Philippine folk tales. Honolulu: University Press of the Pacific, 113-114.

Cornelius-Takahama, V., 1999. Sisters’ islands. Singapore: National Library Board [online]. Available at: http://infopedia.nl.sg/articles/SIP_185_2005-01-20.html [Accessed 10 September 2010]

Corporate Communications Office, Nanyang Technological University. Kudos for Student Filmmakers [online] Available at: http://enewsletter.ntu.edu.sg/classact/Dec10/Pages/cn6.aspx

Criticine: Elevating Discourse on Southeast Asian cinema, [online] Available at: http://www.criticine.com/profile.php?id=9 [Accessed 15 September 2010]

Engel, V., 2009. Tradigital mythmaking: Singapore animation for the 21st century (preface). In Hannes Rall, Tradigital Mythmaking. Catalogue of the exhibition at the Goethe-Institut Singapore and the Singapore international film festival 2009. Singapore: Nanyang Technological University, 5.

Guillermo, A., 1996. The Evolution of Philippine Art. In J. van Fenema (ed.) Southeast Asian Art Today. Singapore: Roeder Publishing, 119-222.

Hodgkinson, G., 2009. Referee report. Tradigital mythmaking: exhibition at the Goethe-Institut Singapore and the Singapore International Film Festival 2009.

Ians, C.T. [n.a.] Geng—the adventure begins (3D) [Film] Malaysian Animation Film Review [online] Available at: http://calcuttatube.com/geng-the-adventure-begins-3d-malaysian-animation-film-review/116248 [Accessed 10 September 2010]

Internet movie database [online] Available at: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0815890/ [Accessed 12 September 2010]

Ker, Yin, 2009. Ma Liang and the Magic Brush between the Virtual and the Real. Tradigital Mythmaking: Singapore Animation for the 21st century. In Hannes Rall, Tradigital Mythmaking. Catalogue of the exhibition at the Goethe-Institut Singapore and the Singapore International Film Festival, Singapore: Nanyang Technological University, 42-45.

Mahamood, M., 2001. The History of Malaysian Animated Cartoons. In J. A. Lent (ed.) Animation in Asia and the Pacific. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Media 21, 2003. Transforming Singapore into a Global Media City. [online] Available at: http://app.mica.gov.sg/Data/0/PDF/4_media21.pdf [Accessed 10 September 2010]

Muthalib, H. & Cheong, Wong Tuck, 2002. Gentle Winds of Change. In A. Vasudev, L. Padgaonkar and R. Doraiswamy (eds.) Being and becoming: the cinemas of Asia. India: Macmillan.

Muthalib, H. Abd., 2007. From Mousedeer to Mouse: Malaysian Animation at the Crossroads. Inter-Asia Cultural Studies: Southeast Asian Cinema, 8(2), 288-297.

Muthalib, H., 2009. Personal interview. Interviewed by Hannes Rall. Singapore and Kuala Lumpur, August 2010.

Muthalib, H., 2010. Southeast Asian Animation History. Next reel festival, Tisch Asia (NYU). Singapore: February 2010.

Ong Pang Kean, B., 2006. Celebrating 120 Years of Komiks from the Philippines: the History of Komiks. Newsarama [online] Available at: http://forum.newsarama.com/ [Accessed 10 September 2010]

Qiu, J., Seah, H. S., Tian, F., Wu, Z. K., and Chen, Q. 2005a. Enhanced Auto Coloring with Hierarchical Region Matching. Computer Animation & Virtual Worlds, 16(3–4), 463–473.

Qiu, J., Seah, H. S., Tian, F., Wu, Z. K., and Chen, Q., 2005b. Feature and Region Based Auto Painting for 2D Animation. The Visual Computer, 21(11), 928–944.

Rall, H. M. (2006-2008). Tradigital Mythmaking Singaporean Animation for the 21st Century. ACRF Tier 1 research grant. Singapore.

Rall, H. M. (2010-2012). Tradigital Mythmaking-The Next Level Adapting Traditional Asian Stories for Digital Animation. ACRF Tier 1 research grant. Singapore.

Rall, H.M. (2011-2013). New Initiative—5 peaks of excellence research grant (NTU). New Computer Animation Techniques for Replicating Singaporean/Indonesian/ Malaysian Puppet Theatre (Wayang Kulit) PI, Hans-Martin Rall. Co-PIs Seah Hock Soon, Henry Johan, Daniel Keith Jernigan, Nanci Takeyama. Singapore.

Rawlings, K., 2003. Chapter two: Scenic Shades, Observations on the historical development of puppetry [online] Available at: http://www.sagecraft.com/puppetry/definitions/historical/chapter2.html [Accessed 10 September 2010]

Snow White, 1937 [Film] Directed by David Hand. USA: Disney. Cinderella, 1950 [Film] Directed by Clyde Geronimi. USA: Disney. Sleeping Beauty, 1959 [Film] Directed by Clyde Geronimi. USA: Disney.

ThaiCinema.org [online] Available at: http://www.thaicinema.org/reviews_20kankluay.asp [Accessed 10 September 2010].

Tan, Wei Keong, 2009. Hush Baby [Film] Singapore.

Wegenast, U., 2010. Three landmarks of German animation, 3rd landmark:

Contemporaries-present day German animation. ANIMFEST 2010 in cooperation with Goethe-Institut Athens, March 11 2010. [online] Available at: http://www.animationcenter.gr/modules/news/article.php?storyid=428&sel_lang=English [Accessed 10 September 2010]

Weimin, M. & Wenju, S., 2000. A Mean Wink at Authenticity: Chinese Images in Disney’s “Mulan”. New Advocate, 13(2), 129-42.

Williamson, R., 2005. Feature animation in Southeast Asia [online] Available at: http: //www.thegreatnamedropper.com/articles/animation.html [Accessed 15 September 2010]

Zhuang, Harry and Zhuang, Henry, 2010. Contained [Film] Singapore.

© Hannes Rall

Edited by Nichola Dobson

![]() To download this article as PDF, click here.

To download this article as PDF, click here.