Introduction

Born in Japan as a Game Boy game, since 1997 the Pokémon franchise has mushroomed worldwide across animated series and movies, trading cards, character toys, and videogames, including a plenitude of tie-in “media-commodities.” In the US market, where it rode an outstanding commercial wave, Pokémon became the “must-have toy” of 1999 as reviewed by the Advertising Age Journal. “Pokémon rage,” the journal emphasizes, created a stir comparable to that caused by Godzilla, and Pokémon videogames “flew off store shelves faster than you can say ‘Pikachu.’” Many American newspapers labeled the toy craze for Pokémon an “invasion,” a “mania,” if not a genuine “culture,” with American kids “buying them, selling them, collecting them, trading them, bidding them up and down, and even leveraging them” with an unprecedented pace (Baylis).

If such a craze died down in 2002, as quickly as it flared up, the “Pokémon culture,” sustained by its rapid commercial and cultural expansion, led to a massive distribution and reception of Japanese animation, play goods and other forms of Japanese popular culture (henceforth called “J-pop culture”) which attracted the attention of the global market (Perper and Cornog; Daliot-Bul and Otmazgin), and eventually became a phenomenon of academic interest (Pellitteri 2002a; Tobin; Allison 2006b).

Since the rise of anime export, partially due to the success of the 1963 series Tetsuwan Atomu, and the initial Western anime boom of the 1970-80s (Pellitteri), an extensive literature has attested to the successful penetration of J-pop culture tropes in Western imagery during the 20th century, especially within the sci-fi domain (Levi; Bolton, Csicsery-Ronay and Tatsumi; Lamarre). At the end of the 1990s, Pokémon marshaled a second J-pop cultural wave, which identified this media franchise as a quintessential “anime system,” namely a transmedia ecology organized around Japanese anime characters due to their iconographic appeal, non-narrative consumption, and inclination toward commodification (Steinberg). According to anthropologist Anne Allison (2003, 2008) Pokémon’s “enchanting capitalism” epitomized Japan’s soft power towards the West, while pocket-monsters’ “virtual intimacy” reflected the anxiety for the future to come, which, according to Tomiko and Harootunian, featured the Japanese great recession and cultural turmoil of the 1990s. From a European perspective, Marco Pellitteri identifies Pokémon as a quintessential Japanese “ludo-narrative cosmos” for its syncretic consumerist nature and its capacity of being successfully “glocalized” in the foreign market. Pellitteri locates anime systems such as that of Pokémon in a wider context concerning the “fusion of Western distributive apparatuses with the diffusion of Japanese content, resulting in a hybridization of structures and contents” (50). According to the author, this process of hybridization significantly hinges on Japanese comics and cartoons’ intermedia development and “passionate reception” in the foreign market in the 1970s, which proliferated, with different intensities, across generations and countries beyond the turn of the millennium (Pellitteri 50). Nonetheless, Pokémon was hardly the only transmedia system based on animation series which resonated on such a transnational axis.

Along with the Poké-boom, but in a kind of reverse push, the global market of the 1990s witnessed the consolidation of another paradigmatic animated universe: that of adult animation. Since the release of The Simpsons (1989-) TV series, these products have globally expanded the audience for TV animation, shifting from childhood entertainment to more complex styles and content for a mature audience (Holloway). At the turn of the millennium, and right after, over fourteen American animated series have emerged as a mainstream television genre characterized by satirical and cynical humour, metalanguage, and self-mocking tropes. Examples of such shows include adult sitcoms like Beavis and Butt-head (1998-2011), Family Guy (1999-), and Futurama (1999-2013), and cross-genre series like Archer (2009-), Rick & Morty (2013-) and Bo Jack Horseman (2014-2020). As with anime, according to transmedia author Tyler Weaver, the “removal from the ‘real world’, where we seek to explain and rationalize everything,” proper to fairy tales and animated storytelling, has allowed these series to grasp realistic themes and to spread across media (231-32).

In this context, South Park (1997-) occupies a strategic place. The long-running primetime series, currently in its 25th season, follows the adventures of four kids who live in the fictional suburb of South Park in Colorado. Created by Matt Stone and Trey Parker for Comedy Central distribution, South Park made its name by lampooning real-world issues with an unprecedented pace, crude humor, and philosophical complexity (Weinstock). In particular, at the base of its growing academic interest, Jeffrey Weinstock argues, is the program’s “hyperawareness” of participating in a “debate about the value and influence of pop culture” (2, 88). Daniel Frim analyses South Park’s “pseudo-satirical” style in detail, focusing on episodes where the references to the real world look incongruous. For Frim, “refraining from making ideological assertions by ambiguously subverting ideologically charged motifs” is what makes South Park’s style “pseudo-satirical” (and not simply satirical), offering an unconventional alternative to other adult series which, I would add, are often parodied by South Park itself (166). Over the decades, in fact, South Park has parodied many famous adult animation shows, including The Simpsons and Family Guy. Notably, without making explicit statements about South Park’s alleged superiority over their competitors, the South Park boys are often in cahoots with characters from other series. Episodes of this type include, among others, “The Simpson Already Did It” (s06e02, 2002), “Cartoon Wars” (s10e3-4, 2007), “Imaginationland” (s11e10-11-12, 2007-2008), and the special episode “The Pandemic Special” (2020).

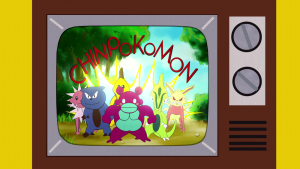

In this sense, the 1999 episode “Chinpokomon” (s03e11) exemplifies this approach by imagining a deceitful military campaign against the USA orchestrated by a Japanese toy company called “Chinpokomon” (meaning “little-penis monsters”). Drawing the story from the context of the American Pokémon boom, Parker and Stone present a three-act narrative where Pokémon-like anime characters persuade American kids to destroy the “capitalist American government” by re-bombing Pearl Harbor, with very hilarious and pseudo-satirical outcomes.[i] On the intertextual level, the episode skilfully narrativizes American amusement, fear and cultural bias over the Japanese entry into the US marketplace by blending together the post-war xenophobic American mindset towards Japanese culture (Tchen) with the “befuddled acceptance” of Pokémon by certain Western adults (Allison 2006b 250). Moreover, due to the nature of the story, and the many analogies between the Pokémon and South Park transmedia systems, the episode itself epitomizes well the progressive hybridization and glocalization of comics and cartoons in the West which Pellitteri and others (Tobin; Denison and Agnoli) discuss in a transnational perspective. Notably, Allison (2006a 249-251) was the first, and perhaps the only one, to recognize the theoretical salience of “Chinpokomon” devoting a few pages to an analysis of the episode for the purpose of deciphering the Western reaction to Pokémon and J-pop culture booming.

This essay aims to propose a textual and intertextual discursive analysis of the “Chinpokomon” episode as a contribution to the debate on contemporary transnational animation, with a focus on the Japan-US axis. Introducing the aesthetics and transmedia traits of the two series, a situated comparison will be proposed of the South Park and Pokémon animation systems. Consequently, an analysis of the episode will be conducted with a particular focus on its three-act narrative. In doing so, American reactions to anime during the Pokémon boom in 1999, and its ambivalent relationship with J-pop culture, as expressed in the fictional figures of “Chinpokomons,” will be discussed.

Pokémon and South Park: Comparing Universes

By combining theoretical strands and terminology from animation and television studies (Azuma; Lamarre; Mittell; Brembilla and De Pascalis), I will outline a set of similarities and differences between South Park and Pokémon which will orient my analysis.

Animation technique. Both series are part of a global 1990s media franchise whose success relies on limited animation techniques. Pokémon employs the low frame rate and freeze frames typical of anime standards (Lamarre 184-206; Steinberg 1-36), whereas South Park leans on a long tradition of limited animation in American TV. Limited animation was, in fact, pioneered in the US by the UPA studio during the 1940s and popularized in American television by Hanna-Barbera’s classic productions such as The Yogi Bear Show (1961-62), The Jetsons (1962-1987) and many others during the Cold War era (Lehman). While Steinberg (5-9) has discussed the influence of American limited animation series on Japanese animators such as Osamu Tezuka, Gary Cross traces a connection between American and Japanese animation and children’s toy consumption back to the 1930s, when the Marx & Co. toy company outsourced its production from the US to Japan (xv). Due to financial limitations, the South Park pilot in 1997 was made with a cutout animation technique that involved the use of construction paper. Even though every subsequent episode of the show has been made with digital technology, South Park continues to emulate the roughness of cardboard as an aesthetic trademark and to distance itself from the realistic style popularized by Disney (Halsall 27). While anime cels are often articulated diagonally and characters suddenly pop in and out, the dynamic use of still images (what Lamarre refers to as the “animetic interval”) is one of anime’s distinctive hallmarks, including in the Pokémon series (Lamarre 194-195). According to Steinberg, the “dynamic immobility of the image and the centrality of the character” are essential features for anime’s media connectivity and commercial survival (7). Similarly, since its very beginning, South Park shared – first as an animation style and then as an aesthetic trademark – this attitude toward limited animation, also due to Trey Parker’s fascination with Japan’s culture. Parker majored in Japanese at the University of Colorado, visited Japan tens of times, and in 2014 built a Japanese Riokan-style house outside of Los Angeles (Turrentine). South Park has devoted many episodes to Japan, in which Parker provided the voice of the Asian characters, such as Emperor Hirohito and Ash in the “Chinpokomon” episode. Notably, this episode was the first one of the series to focus on Japan, showing an image of a Japanese city in the South Park style (a branded Tokyo skyline with the backdrop of Mt. Fuji), while in the episode “Good Times with Weapons” (2004, s08e01), Parker and Stone hilariously “switch[ed] back and forth” between the boys’ iconic cardboard style and the fast-paced, shonen manga style (Weinstock 12).

Storyworld. Both fictional universes are centered around a group of ten-year-old kids, who over time encounter countless characters in a well-structured imaginary geography. However, if South Park mainly relies on episodic narratives (with the infamous “death of Kenny” as a distinctive serial trope), Pokémon exemplifies a case of storytelling oriented toward seriality. Additionally, the character design of South Park’s four main characters (henceforth “the boys”) and that of the Japanese “pocket-monsters” is very basic and easy-to-sketch, mostly counting on a “kawaii” style. Kawaii (meaning “adorable”) generally identifies a culture of/for cuteness-related aesthetic which has become a prominent aspect of J-pop culture since the 1970s. Adopting a transnational perspective, Marco Pellitteri highlights a reciprocal fascination and development of kawaii-related characters between America and Japan’s animation traditions, from Disney’s Mickey Mouse and Bambi (whose “big eyes” influenced Tetzuka Osamu’s early characters design in the 1940s) up to anime/manga characters such as Doraemon, Hello Kitty, Arale-chan, and Pikachu whose roundness, compressed shape, and friendliness standardized the kawaii aesthetic and were echoed in Barbie and Furby toys (2002b, 192-199). If, following Pellitteri, Pokémon are quintessentially kawaii for their “exaggerated roundness, puppy look, large eyes, elementary features, soft and graceful shapes”, it is not hard to assert that South Park’s boys share more than one of these graphic elements (197). In particular, their design resembles that of Doraemon, with a gigantic, rounded head, little ball hands and big ball eyes joined together. Moreover, they are often presented as innocent kids and dubbed with a “hyper-childlike” voice (especially Kenny, whose voice is muffled due to his hoodie). In contrast, South Park’s adult world is depicted in an uglier and more grotesque way, and the parents have more angular, long-limbed and well-proportioned features. We also find this graphical duality in the portrayal of the human characters in Pokémon, although they remain much closer to the kawaii aesthetic, whereas in South Park, characters (including the boys) take on behaviors and traits that are far from being “cute”. This mix of kawaii and anti-kawaii elements, I argue, characterizes South Park’s storyworld and provides an additional link with the anime tradition.

Media system. In terms of transmedia strategy, the South Park franchise exemplifies an unbalanced extension of its storyworld towards what Jason Mittell would dub its “core narrative,” namely the serial animated adventures of the boys. The South Park franchise, in fact, revolves around the animated series which, season by season, set the pace and the setting of its related merchandise and transmedia extensions. In contrast, Pokémon better balances its ludo-narrative galaxy across anime, videogames, and trading cards. By introducing the character of Pikachu (whose significance I will discuss later) in the anime series of 1997, the Pokémon franchise enlarged its storyworld and increased its complexity, compared to the basic plot sketched in the Pokémon Red (1996) videogame (where a male hero takes a journey in the region of Kanto to become the champion of the Pokémon trainers). For many years now, Pokémon has remained one of the highest-grossing media franchises in the world, with a total company capital of $2 billion (The Pokémon Company 2022). With blockbuster movies, multi-platform videogames, several tv seasons, an infinite number of toys, and many Wiki fandom pages, after almost thirty years in the business Pokémon and South Park can both be considered seminal franchises in the field of global animation. As Steinberg (viii) points out, if “media mix” is the Japanese version of Jenkin’s “convergence” (both theorized at the turn of the millennium), Pokémon certainly charts its iconic global manifestation, solidifying the presence of Japanese toys across the world (Allison 2006b, 237). Accordingly, it would also be responsible for “exposing” the cultural biases exercised by the US audience against the Japanese cultural penetration via media mix. For its part, South Park is nowadays considered a “titan” of adult TV animation, second only to The Simpsons for number of seasons and media exposure.

Historical context. The public fear of the Pokémonization of American values was fuelled by an anti-export demonization of Japanese media by the US press in the 1997-98 (Marschall 56-64). Pellitteri (2002a) and Allison (2006b) have discussed in depth some forms of cultural resistance to Pokémon that occurred in the Western market despite the franchise’s outstanding commercial success, connecting it to orientalist stereotypes about Asian toxic masculinity and moral values, along with an economic fear of Japan’s post-war technological and cultural rise in the global market, especially in the American context, where Pokémon trading cards were banned from many schools.

South Park, as well, has fuelled several controversies, leading to online cancellation petitions and the banning of South Park clothing in some American schools (Weinstock 3).[ii] Both Pokémon and South Park were notably targeted by the advocacy group Action for Children’s Television co-founder Peggy Charren, who labeled the shows respectively as “the bottom line of the corporations” (Gellene), and “dangerous to democracy” (Marin 57). As discussed by Jenkins, while Charren and her allies feared that the conversion of cartoons into ads for tie-in toys would eventually “stifle youngsters’ imaginations”, franchised toys of the 1980s and 1990s have become part of the shared memories and “tokens of stories and entertainment experiences” which were deeply meaningful for two generations of kids.

Moreover, the Pokémon media dissemination and cultural translation could also be framed in a wider, and less evident politics of agreements between American and Japanese corporations. As the executive producer of the Pokémon anime, Kubo Masakazu (2002), pointed out, the first Pokémon movie, which smashed the American box office in 1999, had to undergo profound changes in terms of music, story, characters, and even animation in order to suit the American market. The aesthetic negotiation made by Masakazu and Warner Bros executive Norman Grossfield allowed Pokémon The First Movie (Yuyama, 1999) to gross nearly $80 million, compared to the $2 million earned by the competing American release of Princess Mononoke (Mononoke Hime, Miyazaki, 1997), just two weeks later. If, on the one hand, this adaptation could prove American “protectionalism” over transpacific imports, on the other hand, it confirms the “localization” of anime as a key strategy for the proliferation of Japanese cultural imports into the foreign market and imagination over the decades (Marschall; Katsuno and Maret). Similarly, soon after South Park’s TV premiere, the show’s rounded aesthetics (which, as I’ve argued, share some elements of kawaii style) facilitated the characters conversion into plush toys, foam stress balls and other merchandise products which sold over $30 million in barely six months (Nixon), and $100 million in the whole of 1998 (La Franco). In this commercial context, it is significant that the “Chinpokomon” episode aired on November 3, 1999, nine days before Pokémon’s American movie premiere.

As illustrated, South Park and Pokémon present several points of contrast and overlap in terms of animation, storyworld, media system and production history. Arguably, this prismatic plane of relationships, together with a certain Western resistance to the anime media mix, underpins the narrative universe of the “Chinpokomon” episode and its epistemological longstanding significance as a cultural artifact of the late 1990.

Stage One: Buy It All!

The show opens with Cartman scolding his cat while sitting on the sofa and watching a Japanese cartoon entitled Chinpokomon. The TV screen shows a blond Ash-like anime hero surrounded by three little monsters. “Someday, I will collect all the Chinpokomon”, he exclaims, “Then I will fight the Evil Power that will reveal itself once all the Chinpokomon are collected… oh?”. On the “oh,” the character tilts his head to one side, showing a typical kawaii expression of joy and cuteness. Suddenly, Cartman affects a similar anime look, now addressing his cat gently (Fig. 1). As the show ends, a commercial urges the young spectators to collect all the Chinpokomons to become the “Royal Crown Chinpoko Master”. While Cartman seems mesmerized by the TV screen, live-action footage of a Japanese woman in a black suit (Saki Miata) appears upon the animated background, and the character shouts with an exaggerated Japanese accent: “Chinpokomon is superior rubber toy, number one!”. As the ad ends with the song lyrics “I’ve got to buy it! Chin-po-ko-mon!”, Cartman instantly forces his mom to take him to the toy store to purchase the toys because, he complains, “people won’t think I’m cool”. Upon arriving there, Cartman is angered to see that everyone else has beaten him to it, and fights with Kenny over the last “Pengin” doll (which is referred to as the “coolest,” but appears to be just a simple penguin with purple feathers). While children are wreaking havoc at the store, at the checkout counter a group of concerned parents is wondering what their children find so amusing about these strange toys and where they came from. As the store manager explains, the toys are “some new big thing from Japan”, concluding that “those Japanese really know how to market to kids”. Then the scene shifts again to the store counter, where kids are watching the same Chinpokomon episode which is now interrupted by the Japanese woman from before, who urges the spectator to buy the toys to “have happy feelings”. As they disperse, all the kids in the store recite robotically: “Must-collect-Chinpokomon”.

This first sequence parodies the national anxiety about the supposed “Nipponification” of America already at work during the launching of Mighty Morphing Power Rangers in 1993 (Allison 2006b, 250). Japanese animation is shown as a primary cultural mediator for the penetration of Asian characters in the US juvenile market and imagination. By mimicking anime facial expressions, Cartman (and later all his classmates) embodies the traits of the so-called otaku culture which threatens the American marketplace: a fondness for alien-like characters, violent competition against peers and, as Azuma (2009) later theorized, an “animalistic” compulsion for collecting goods which, as in the case of Chinpokomons, appear visually alien. At the same time, when kawaiized Cartman shows a sort of kindness towards his cat, he alludes to Pokémon’s ability to enhance empathy and friendliness. The inclusion of the live-action advertisement seems to parody anime’s supposed ability to leverage compelling visuals to convey subliminal commercial messages. In doing so, the scene also codifies live-action moving images as vectors of commercial persuasion and corporate interests, a trope that would recur during the episode.

The scene introduces the Chinpokomon characters as a parodic experiment of transpacific visual hybridization. In fact, the monsters featured on Cartman’s tv look like a 2-D rough assemblage of anime aesthetics, canonical Pokémon features, and portmanteau names: “Furrycat”, “Donkeytron”, “Pengin” and… “Shoe”, modest footwear that arguably mocks the very nature of the Pokémon toys as a pure commodity, ridiculing the idea of embedding consumer goods into a narrative universe just to be marketable across media (Fig. 2).

However, if the creatures depicted on the Pokémon playing cards are certainly items of value and monetary exchange, Pikachu, as the leading pocket-monster, owes its global success to its introduction in the anime series of 1997. According to Pellitteri (2002b, 237), Pikachu’s character performs three functions: 1) Narrative, epitomizing the anime’s leading Pokémon character and Ash’s “best friend”; 2) Symbolic, embodying kids’ desires for autonomy and individuality due to its refusal to be stored in the Pokéball and to evolve; and lastly 3) Commercial, as an attractive “cute monster” which, according to marketers, exerts a certain trust on parents, thus ensuring its saleability.

Analogously, Chinpokomon’s leading doll and company logo “Lambtron” seems designed to serve the same functions, except for… the giant cannon shown on its right limb (Fig. 3). The “softness” of its kawaii look (arguably a mash-up of Pikachu, Winnie the Pooh, and Lisa Simpson) combined with the “power” of its cyborg-like rifle-arm (reminiscent of G.I. Joe and Masters of the Universe action figures), visually synthesizes the ambiguous “soft power” of this dystopic J-pop cultural operation. On the story level, in fact, it introduces the militarist subplot of the show, anticipating its warfare escalation. From the intertextual point of view, it displays the fear of a supposed Japanese cultural and military “anime counterattack” on America, which I have mentioned before.

Stage Two: From Collection to Invasion

Indeed, Lambtron is soon revealed to be a trojan horse for the Japanese army. After we see the boys introducing Kyle to the “quest” for becoming the Chinpoko Master, convincing their mate to buy a J-toy despite him recognizing it as a consumerist fad, we return to the store where Kyle has just purchased a Lambtron. As the kid exits the shop, and the cashier turns off the lights, a voice from the store shelves draws his attention. When the man gets a Lambtron and squeezes it, the toy exclaims: “Hurry up and buy me”. But after a second and third squeeze, it exclaims “Down with America!”, and “I love you. Let’s be best friends and destroy the capitalistic American government!”.

This scene introduces the audience to the second stage of Chinpokomon’s invasion of South Park, by making explicit the very nature of the Chinpoko-monsters as a vehicle of Japanese propaganda. To make it more hilarious, the creators set the scene at night, giving it a horror twist recalling the classic black comedy Gremlins (Joe Dante, 1984), where a furry Chinese critter morphs into a murderous monster.[iii] Moreover, we experience this transformation through a first-person shot of the cashier grabbing the toy, which resembles the graphical perspective of a first-person shooter video game.

This shot posits an initial link between the game world and that of warfare, which becomes explicit when, the day after, we see the boys on the sofa being engaged with a compelling gaming console. As Kyle enters with his new toy, Cartman laughs at him for not getting the special Chinpokomon controller they are playing with. While the kids are compulsively gaming, the shot goes to the tv screen where a roughly pixelated blonde Ash reminds them to buy all the toys, adding: “So first I’d better go to Hawaii and visit Pearl Harbor.” As the boys start attacking a digital version of The Oahu lagoon’s harbor, the Japanese woman pops up again on the screen, encouraging the kids to keep bombing. From “Got to buy it all”, the Chinpokomon tagline now mutates to “Try to bomb the Harbor!” As the blasting gets more intense, Kenny begins to convulse under the sofa, while Cartman and Stan continue playing.

This scene draws a connection between the very act of buying Japanese toys and that of “bombing” American territory, making clear to the audience the true nature of Chinpokomon: through the amusing language of Japan’s media mix, they are trying to persuade South Park kids to collect cute toys and engage in a sort of “war game” which hides deep anti-American propaganda. This understanding is reinforced afterward, when in a brief scene the toy cashier goes to the Chinpokomon headquarters in Japan, asking for an explanation about Lambtron’s speech. Here the company’s executives, President Hirohito and his partner Mr. Ose, show up for the first time, trying to reassure the man that the accident won’t happen again. Once the cashier says he is not satisfied with their answer, they divert the argument by saying (and gesturing) that the Americans “have very big penis” in comparison to Japanese people. After a group of Japanese women in traditional clothes enters the scene, cheering for the cashier’s “large penis,” the man exits happily satisfied. Then, Hirohito gets angry and slaps Mr. Ose for letting this detail come out, calling for a sit-down meeting. The “penis trick” becomes a hilarious leitmotif, which I will discuss in the next paragraph. The boys themselves also appear to be cognitively “assaulted” by such a media operation, which suddenly mutates its advertising claim from “I must buy ’em all” (a parody of Pokémon’s famous slogan “gotta catch ‘em all”) into the way more aggressive gaming goal “try to bomb the Harbor,” shifting from a kawaii anime to militarist and WWII-reminiscent imagery.

If television’s cognitive bombing of the kids could appear overstated, Kenny’s epileptic attack (and his enduring hypnosis across the episode) explicitly references the so-called “Pokémon shock”. This is the term the Japanese press used to label a case of massive seizures suffered by several hundred children while watching an episode of the Pokémon series on December 17, 1997. This incident led to medical research which compelled Television Tokyo, the Japanese Pokémon broadcaster, to compile a production guideline “in the interest of minimizing the risks of viewer exposure to harmful stimuli”.[iv] Notably, the P-shock news spread before the US Pokémon premiere in 1998, contributing to an explosion of academic and popular Western media fear of the upcoming Japanese TV show.

At this stage, one is tempted to say that “Chinpokomon” sketches a trivial picture of a “neo-feudal” Japanese corporation, a global brainwashing machine to recreate the Japanese imperialism through anime and popular media (Allison 2006b, 250). And indeed, the absurd story of re-bombing Pearl Harbour, and taking down America from within via anime propaganda may reinforce this understanding of the episode in connection with other US popular iconographies and narratives sustaining the idea of an impending war with the East since the late 1930s, including Arthur Leo Zagat’s sci-fi story Tomorrow (1939), which recounts the future invasion of America by the “yellows” and the “Remember Pearl Harbor” manifest (1942) which placed the fight with Japan “into one long progression of conflicts between brave [American] individuals and treacherous hordes” (Tchen 287-388).

As anime and manga helped Japanese society mitigate the spectre of the nuclear bomb during the Reconstruction era (Allison 2006b, 35-65; Sthal and Williams), at the same time it nurtured a certain suspicion in Western public opinion, as many anime of the time (especially the super robot sagas of the 1970s which revolve around unique robots with super-natural powers) showed an explicit antagonism, if not a desire for revenge, towards the Allied nations (Nacci). The “Yellow Peril,” a pervasive racist idea depicting East Asian people as dangerous to the Western world (Tchen and Yeats), certainly persists in the Pokémon era. In this particular case, it manifests in a way that Rick Marschall has summarised as follows: “I’ve noticed that some salacious observers in America have suggested that where the Japanese failed at Pearl Harbour, they instead managed to hit the mark thanks to Pokémon” (44, italics mine).

Is this really the case? Do South Park’s directors depict Japanese anime in a such naïve or even “antiliberal” way, as Anderson (2005) would argue? Or do they, as Allison leaves open to discussion, parody the failure of the US adults to comprehend “what kids are up to these days, both at play and in ‘real’ life?” (2006b, 251).

Stage Three: Get the Power in Your Hands!

During the night, while Cartman is asleep, an antenna sprouts from his Chinpoko-monster. It casts a light signal out of the window, which joins other signals and goes to a satellite, bouncing them to the headquarters of the Chinpokomon Toy Corporation. Here each toy appears on its own screen on the company’s video wall while President Hirohito, speaking in Japanese, announces his plan to retake Pearl Harbor. In front of him, beyond the executives, a line of soldiers load their rifles in unison.

After this revelatory scene, we see Stan’s parents on the sofa watching Chinpokomon, trying to understand “if it’s teaching him good moral values.” After watching a seemingly nonsense dialogue between two Chinpoko Masters, the parents conclude that the anime is not vulgar nor violent, but simply “stupid,” so basically harmless. This is a vision shared by many, as Allison reports after a roundtable with a group of parents, which led to a “befuddled acceptance” towards Pokémon’s seemingly incongruous storytelling and game design during its American boom (2006b, 250).

From now on the main storyline shifts in a more surrealistic vein, following the hilarious “third stage” of Chinpokomon’s operation, namely the recruitment and training of South Park’s kids by the Japanese air force, and the consequent counteroffensive of their concerned parents. In fact, the toy company gathers the kids in the “Big Weekend Chinpokomon Camp” where, from a gigantic concert stage surrounded by video walls, the corporation’s president reveals that the “Evil Power” is nothing but the American government, transforming the event into a massive Japanese language course and military training (Fig. 4).

Like the P-Shock sequence, this scene is drawn from a real media event: the Pokémon League Summer Training Tour, which took place in 1999 at the Mall of America in Minneapolis. Involving over 44, 000 participants, the event was the first national tournament of the Pokémon trading card game, attesting to its national popularity. Notably, the game was released on January 1999 by the American games manufacturer Wizards of the Coast which, after announcing the acquisition of Pokémon trading card rights from Nintendo, proudly stated: “We believe the invasion of the Pokémon trading card game into North America will be a tremendous success […] We are excited to be working with Nintendo to reproduce the Pokémon trading card game craze in North America. Our advice to future Pokémon trainers is – Get the power in your hands! [italics mine]” (Wizards of the Coast, 1998). Seemingly, by joining the Chinpokomon Camp, the boys have the chance to put into practice the rules, goals, and routines of what has appeared to be just a simple child’s play.

In this sense, South Park’s directors seem to employ the same metaphor chosen by Michel Foucault, i.e. the military system, to parody the informal, yet effective, regime of power exercised by a media system to entrap new clients and obtain consumerist obedience. As Foucault remarked on several occasions (1988, 2020), civil obedience could be obtained not only with violence but also through the production and exchange of signs that are enmeshed within specific apparatuses and “technologies”. Taking Foucault’s view even further, it’s not risky to glimpse in the Chinpokomon media mix the narrativization of a disciplinary “block,” namely a concerted assemblage of communication systems, goal-oriented activities, and relations of power (Foucault 337-339). As shown, the boys are first introduced to a system of communication (that of Japanese animation, kawaii expressions, gaming, and language). Afterward, they are induced to take action (getting the toys, and bombing the harbor) and therefore to recognize a power relation (the Japanese people are friends, America is the “Evil Power”) with the eminent goal of taking down America from inside. Here South Park’s satire is particularly striking, since Ronald Reagan, in his famous 1983 speech, termed the Soviet Union an “Evil Empire”, fostering a “civilization clash” and an “us vs them” discourse that would resonate in future American conflicts in the Middle East (Tchen 279).

The effect of this Foucauldian power regime becomes explicit in the eyes of adults as soon as the kids acquire an anime look by emulating the cute facial expression and the behaviors of anime characters. At the beginning of this scene, Cartman and all his friends appear with enlarged eyes and smile, now evoking Japanese kawaii aesthetics more explicitly. Their eye line curves and the mouth enlarges in a big “manga” smile with tongue and teeth visible. At the same time, they also make fun of their schoolteacher Mr. Garrison by speaking in Japanese.

Concerned by this abrupt “Japanification” of their children, the parents gather in the city hall, and with the endorsement of the mayor, try to fight the hegemonic anime fad by creating a new one. Following this scene, we see the boys on a sofa at the “South Park Market Research Laboratories,” looking at a big screen flanked by two lab technicians. The technicians’ screen advertising clips for two experimental toys made in the USA. Significantly, these ads are produced in live-action, presenting two bizarre products which the boys dismiss as “totally gay”: “Wild Wacky Action Bike,” a bicycle almost impossible to steer which ends up exploding under a truck, and “Alabama Man,” an adult male action figure shown with a beer can and a bowling ball under the confedered flag, with an action button for “knocking out his wife.” The fictional action figure of Alabama Man is seemingly a parody of the racist American toy “Alabama Coon Jiggers,” produced by Louis Marx & Co. in 1919. This connection seems to not be trivial since, as I pointed out earlier, Louis Marx was one of the first US manufacturers to outsource its production in Japan during the 1930s. Moreover, Cartman’s homophobic line (“totally gay”) should be intended as a critique to the normative image of masculinity and manhood promoted by Western children’s marketing (Foss). As a core feature of the South Park series, the sequence contrasts the perspective of the young Americans with that of the adults, wherein the latter are characterized by moral hypocrisy, class, race and gender prejudices, yellow perilism, and capitalist myopia.

From now on, in fact, the story progresses towards the radicalization of the Japanized boys against their American parents, shifting from a seemingly cultural war to a military one. In the next scene, we see the parents lined up at the roadside as a troop of South Park kids in Imperial Japanese military uniforms parade waving the Japanese state and red flags, while shouting “Ottawa Beikoku!” (“Down with the USA!”).

Sharon, Stan’s mother, steps in and tries to take her son back home, but the troop pushes her back while Mr. Ose reassures the woman, saying that “everything is okay”. After Sharon asserts that “it’s not ok!”, the Japanese man replies “Oh, but you have such a large penis, uh”. As with the cashier and throughout the episode, whenever they are questioned, Japanese adults dispel the Americans’ suspicions by assuring them that they have “such a large penis” compared to theirs. These lines seem built upon Edward Said’s notion of “orientalism” (1978) as a Western-style for authorizing stereotyped knowledge of Asian people to reassess its imperial rule. In this case, by reorienting an orientalist sexual stereotype – that of Asian men having small penises and being submissive – towards the male westerners, the “penis trick” transforms a discourse of oppression into a weapon of subversion. In terms of script, the result is hilarious and allows South Park’s directors to highlight the discourse on “manhood” underpinning the US-Japan conflict as a matter of virility, such as war itself, as feminist theory has put forth (Hutchings; Duriesmith). Moreover, it sheds light on the White male fetishization of Asian women and Asian goods, which has taken on a new significance since Japan assumed a hegemonic position in the field of technology, manufacturing, and finance (Morley and Robins 163-66). This “orientalism in reverse,” Morley and Robins argue, is far from being a confrontation between “cultural narcissisms,” hiding the Western fear of a “cultural emasculation” associated with the loss of its technological hegemony (167).

It is no accident that Sharon, a woman, notices the fallacy of the argument, coming out with an idea to get the kids to “stop liking Chinpokomon.” Conversely, US president Bill Clinton (whose “virility” became a matter of public discussion during the Lewinsky scandal) seems not to understand what is at stake; during a special announcement from the Oval Office, he reassures the population about the growing Japanese military presence by proudly stating: “I spoke with Mr. Hirohito this morning, and he assured me that I have a very large penis. He said it was mammoth, dinosauric, and absolutely dwarfed his penis, which, he assured me, was nearly microscopic in size”.

In the last scene, as dozens of child troops are getting ready to board jet planes, Sharon marshals a group of parents carrying Chinpokomon toys. As they pretend to support their children and to be crazy about the “Chinpoko stuff”, the Japanese media mix suddenly loses its “coolness” in their boys’ eyes. As a result, the kids toss away the Chinpokomon onto a pile and leave the airfield, while the parents cheer and President Hirohito despairs, leading the story to its conclusion.

With this conclusion, which leaves the South Park boys unsure if any lesson can be drawn from the whole story, South Park seems to point its satire toward global consumerist culture. Transnational media consumption, as the story exemplifies, can be put in the service of global warfare, which represents its ultimate outcome. As suggested by Paul Virilio’s classic War and Cinema (1989), and later revised by Friedrich Kittler, television and information technologies owed their commercialization in the post-war era to their employment as a military “invisible weapon” for enemy surveillance and bomb piloting during the WWII. “It is no accident”, Kittler remarks, “that the age of media technologies is at the same time the age of technical warfare” (41-42). In this sense, the image of a Japanese toy functioning as a military antenna provides an effective allegory. Furthermore, the episode echoes Tchen’s argument that “Yellow Peril fears promote an American culture of war-making” (278) when showing both kids and parents holding the Chinpkomon as a weapon in order to – paraphrasing the slogan – “get the power in their hands” (Fig. 5).

Moreover, commenting on several acts of violence among young players and collectors in the US provoked by “bad trades” of Pokémon cards, Allison remarks: “Violence is always the underside of this [consumerist] dreamworld, given that desires are never sated (in an endless quest to “get” more where accumulation confers power[s], if only of a virtual/fantasy kind) and great disparity exists in the means available to consume in America today” (2006b, 205, italics mine). It is no coincidence that it is Kenny, the lowest-income member of the core characters, who remains “C-shocked” even beyond the fad and eventually dies after accumulating a series of rats that burst from his stomach in the very last shot.

Conclusion

Being a paradigmatic example of adult and anime series of the complex TV era, South Park and Pokémon have confronted their transmedia systems in the “Chinpokomon” crossover episode. Mixing limited and cutout animation, adult cartoons, and kawaii anime tropes with a cutting-edge historical timing and a pseudo-satirical stance, the episode offers a sophisticated discourse on transpacific animation, also charting topics at the core of contemporary transmedia and television studies.

As my textual analysis has revealed, the show exposes, and parodies, the complex power dynamics between the United States and Japanese popular media, their reciprocal biases, stereotypes, and will of power which echo Foucauldian and Orientalist theories and are based on a long-lasting discourse of “Yellow peril.” To do so, South Park’s directors set up a classic three-act narrative, which exemplifies the show’s unconventional satirical style at its best. In addition, the plot intersects with real-world hot themes such as the Poké-mania, the P-shock accident, and the media debate on masculinity over Clinton’s impeachment. It coalesces references to US-Japan military history, dynamics of consumption resistance, children’s aggressive marketing, and Western and Eastern animation tropes, resulting in bizarre character designs like that of Lambtron, and in narrative gimmicks such as that of the “penis-trick.”

These pseudo-satirical elements, as Frim would label them, act like a semantic “gravity centre” which helps frame the episode on a wider intertextual level. As I’ve discussed, “Chinpokomon” takes a stance over the orientalist and warfare discourse underlining neoliberal market forces and masculinity, in a period, at the turn of the millennium, where anime media mix and Japanese technology solidified its global presence, and the Western audience oscillated between fear and fascination, demonization and passive acceptance towards Japan. With a visual and narrative connection between “buying” and “bombing,” the episode highlights the seemingly hidden linkage between warfare and capitalist culture, by foreseeing topics in contemporary media theory regarding “gamification” and “weaponization.” In this perspective, the analysis buttresses my hypothesis that, due to its media specificity, adult animation is particularly able to intercept audiences’ media sensibility and to problematize the contemporary media condition (Gatti). Furthermore, reconstructing the Pokémon phenomenon almost a quarter-century after its global boom through South Park could inspire future studies on the American-European-Japanese animation axis. The show, in fact, could be seen as one of the frontrunners of the contemporary hybridization of American and Japanese animation narrative tropes (ex. Rick & Morty) and techniques (from Animatrix to Marvel Future Avengers) along with several cases of re-dubbing, broadcasting or remaking of Japanese cult anime series by Western companies due to a new global anime boom via streaming platforms during the 2010-20s (examples include the recent Netflix distribution of Devilman Crybaby, Neon Genesis Evangelion, and the 1990s Pokémon series itself). As Pokémon characters have witnessed a new global craze with the launch of one of the most advertised AR mobile games, Pokémon Go (Nintendo, 2016), Pokémon game design has established itself as a standard gameplay formula and is notably employed (and parodied) in games derived from adult cartoons such as Rick & Morty’s Pocket Morty (2016) and South Park: Phone Destroyer (2017). Chinpokomons, for their part, are still “alive” in the South Park storyworld such as in the role-playing game South Park: The Stick of Truth, with an additional cameo of Lambtron in “The Pandemic Special” episode in 2020.

Giuseppe Gatti is a post-doc research fellow and adjunct professor at the Department of Philosophy, Communication and Performing Arts of Roma Tre University. He is author of Dispositif. An Archaeology of Mind and Media (Dispositivo. Un’archeologia della mente e dei media, Roma TrE-Press, 2019) and Hip-hop Roadmap (Stradario hip-hop, Alegre, 2020). Under the pseudonym “Nexus” he is an active performer, director, and media artist. His research topics include film and media theory, anime and tv series, media presence, transnational consumption, and hip-hop culture.

Works Cited

AA.VV. “Seizures Induced by Pokémon Episode: A Bibliography”, Anime and Manga Studies, 2017. https://www.animemangastudies.com/2015/10/20/seizures-induced-by-pokemon-episode-a-bibliography/

AA.VV. “1999 The Year in Products (cover story)”. Advertising Age Journal, vol.70, no. 52, 1999, p. 28.

Allison, Anne. “Portable Monsters and Commodity Cuteness: Pokémon as Japan’s New Global Power”. Postcolonial Studies, Vol. 6, n. 3, 2003, pp. 381-395.

Allison, Anne. “New-age Fetishes, Monsters, and Friends: Pokémon in the Age of Millennial Capitalism”. Japan after Japan: Social and Cultural Life from the Recessionary 1990s to the Present, edited by Yoda Tomiko and Harry D. Harootunian, 2006a, pp. 331-357.

Allison, Anne. Millennial Monsters: Japanese Toys and the Global Imagination. University of California Press, 2006b.

Allison, Anne. “Pocket Capitalism and Virtual Intimacy: Pokémon as Symptom of Postindustrial Youth Culture.” Figuring the Future: Globalization and the Temporalities of Children and Youth, edited by Jennifer Cole and Deborah L. Durham, School for Advanced Research Press, 2008, pp. 179-196.

Anderson, Brian. South Park Conservatives: The Revolt Against Liberal Media Bias. Regnery Publishing, 2005.

Azuma, Hiroki. Otaku: Japan’s Database Animals. University of Minnesota Press, 2009.

Baylis, Jamie. “Invasion of Pokemon”, The Washington Post, August 29, 1999, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/business/1999/08/29/invasion-of-pokemon/6362bbf5-c6ab-4bc1-a9e1-6b99e982e737/

Bolton, Chris, Csicsery-Ronay I., and Takayuki T. (eds.). Robot Ghosts and Wired Dreams. Japanese Science Fiction from Origins to Anime. University of Minnesota Press, 2007.

Brembilla, Paola and De Pascalis, Ilaria (eds.). Reading Contemporary Serial Television Universes: A Narrative Ecosystem Framework. Routledge, 2018.

Cross, Gary. “Foreword”, Millenial Monsters, edited by Anne Allison, University of California Press, 2006, pp. xv-xviii.

Daliot-Bul, Michal and Otmazgin, Nissim (eds.). The Anime Boom in the United States: Lessons for Global Creative Industries. Harvard University Asia Center, 2017.

Denison, Rayna and Agnoli, Francis (eds.) Animation studies. Special Issue: Transnational animation, 2019, https://journal.animationstudies.org/category/transnational-animation/

Duriesmith, David. The Masculinity and New War. The Gendered Dynamics of Contemporary Armed Conflict. Taylor & Francis Ltd, 2016.

Foucault, Michel. Technologies of the Self: A Seminar with Michel Foucault. University of Massachusetts Press, 1988.

Foucault, Michel. “The subject and power”. Essential Works of Foucault 1954-1984. Vol. 3 – Power, edited by James Faubion. New York: New Press, 1994.

Foucault, Michel and Rabinow, Paul (ed.). The Foucault Reader, Penguin Classics, 1991.

Frim, David. “Pseudo-Satire and Evasion of Ideological Meaning in ‘South Park’”. Studies in Popular Culture, Vol. 36, No. 2, 2014, pp. 149-171.

Foss, Katherine. Beyond Princess Culture: Gender and Children’s Marketing. Peter Lang, 2019.

Gatti, Giuseppe. “Plenitudine Visuale. Note di Cultura Visuale nel Congegno ‘Salva Progressi’ di Rick & Morty”, SigMa, Vol. 5, 2021, pp. 493-521.

Gellene, Denise. “What’s Pokemon? Just Ask Any Kid”. The Los Angeles Times, December 10, 1998, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1998-dec-10-fi-52393-story.html

Halsall, Alison. “Bigger Longer & Uncut. South Park and the Carnivalesque”. Taking South Park Seriously, edited by Jeffrey Weinstock, State University of New York Press, 2008, pp. 23-38.

Holloway, David. “From ‘The Simpsons’ to ‘Solar Opposites,’ Inside TV’s Adult Animation Boom”. Variety, July 9, 2020, https://variety.com/2020/tv/features/simpsons-solar-opposites-bento-box-adult-animation-boom-1234699492/

Hutchings, Kimberly. “Making sense of Masculinity and War”, Men and Masculinities, Vol. 10, No. 4, 2008, pp. 389-404.

Jenkins, Henry. “He-Man and the Masters of Transmedia”, May 20, 2010, http://henryjenkins.org/blog/2010/05/he-man_and_the_masters_of_tran.html

Katsuno, Hirofumi, and Maret, Jeffrey. “Localizing the Pokémon TV Series for the American Market”. Pikachu’s Global Adventure: The Rise and Fall of Pokémon, edited by Joseph J. Tobin, Duke University Press, 2004, pp. 80-107.

Kittler, Friedrich. Optical Media. Berline Lectures 1999. Polity, 2012.

La Franco, Robert. “Profits by the Gross”. Forbes, September 21, 1998, p. 232.

Lamarre, Thomas. The Anime Machine: A Media Theory of Animation. University of Minnesota Press, 2009.

Lamarre, Thomas. The Anime Ecology: A Genealogy of Television, Animation, and Game Media. University of Minnesota Press, 2018.

Lehman, Christopher. American animated cartoons of the Vietnam era : a study of social commentary in films and television programs, 1961-1973. McFarland & Co, 2007.

Levi, Antonia. Samurai from Outer Space: Understanding Japanese Animation. Open Court, 1996.

Marin, Rick. “South Park: The Rude Tube”. Newsweek, March 23, 1998, pp. 56–62.

Marschall, Rick. “Il triplice avvento dei Pokémon in America”. Anatomia di Pokémon, edited by Marco Pellitteri, Edizioni Seam, 2002, pp. 43-64.

Masakazu, Kubo. “Why Pokemon was successful in America”. Japan Echo, Vol. 27, No. 2, 2002, pp. 59-62.

Mittell, Jason. Complex Tv: The Poetics of Contemporary Television Storytelling. New York University Press, 2015.

Nacci, Jacopo. Guida ai Super Robot. L’Animazione Robotica Giapponese dal 1972 al 1980. Bologna: Odoya, 2016.

Nixon, Helen. “Adults Watching Children Watch South Park”. Journal of Adolescent

and Adult Literacy, Vol. 43, No. 1, September, 1999, pp. 12–16.

Pellitteri, Marco. The Dragon and the Dazzle. Modes, Strategies and Identities of Japanese Imagination. A European Perspective. Tunué, 2010.

Pellitteri, Marco. “Kawaii Aesthetics from Japan to Europe: Theory of the Japanese ‘Cute’ and Transcultural Adoption of Its Styles in Italian and French Comics Production and Commodified Culture Goods”. Arts, Vol. 7, No. 24, 2018, pp. 1-21.

Pellitteri, Marco (ed.). Anatomia di Pokémon. Cultura di Massa ed Estetica dell’Effimero fra Pedagogia e Globalizzazione, Edizioni Seam, 2002a.

Pellitteri, Marco. “Estetica kawaii e sviluppo intermediale da Topolino a Pikachu”. Anatomia di Pokémon, edited by Id., Edizioni Seam, 2002b, pp. 177-247.

Perper, Timothy. and Cornog, Martha (eds.). Mangatopia: Essays on Manga and Anime in the Modern World. Libraries Unlimited, 2011.

Said, Edward. Orientalism, Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1978.

Steinberg, Marc. Anime’s Media Mix: Franchise Toys and Characters in Japan. University of Minnesota Press, 2012.

Stahl, David and Williams Mark (eds.). Imag(in)ing the War in Japan: Representing and Responding to Trauma in Postwar Literature and Film. Brill, 2009.

Morley, David and Robins, Kevin. Spaces of Identity: Global Media, Electronic Landscapes and Cultural Boundaries. Routledge, 2002.

Tchen, John Kuo Wei, and Yeats, David (eds.). Yellow Peril! An Archive of Anti-Asian Fear. Verso, 2014.

The Pokémon Company, “Company Information”, 2022, https://corporate.pokemon.co.jp/en/aboutus/company/

Tobin, Joseph (ed.). Pikachu’s Global Adventure: The rise and Fall of Pokémon. Duke University Press, 2004.

Tomiko, Yoda, and Harootunian Harry (eds.). Japan after Japan: Social and cultural life from the recessionary 1990s to the present, Raleigh, NC: Duke University Press, 2006.

Turrentine, John. “South Park Co-Creator Trey Parker’s Hilltop Retreat in Colorado”, Architectural Digest, May, 2010, https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/south-park-trey-parker-colorado-home

Virilio, Paul. War and Cinema: the Logistics of Perception, Verso, 1989.

Weaver, Tyler. Comics for Film, Games and Animation. Using Comics to Construct your Transmedia Storyworld. Focal Press, 2013.

Weinstock, Jeffrey (ed.). Taking South Park Seriously. State University of New York Press, 2008.

Wizard of the Coast, “Wizards of the Coast Catches Pokémon Trading Card Game Rights!”, 1998, https://web.archive.org/web/19990221060236/http:/www.wizards.com/Corporate_Info/News_Releases/WotC/Pokemon.html1998

Young, Liam Cole. “Imagination and Literary Media Theory”. Media Theory Journal. Manifestos, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2017, pp.17-33.

[i] Japan and “Japanization” are a recurring topics in the South Park universe. Since the second Parker and Stone animated short film The Spirit of Christmas. Jesus vs Santa (1995), in which Jesus fights against Santa Claus, mocking the Mortal Kombat gaming style, several episodes of South Park have focused on Japan or Japanese phenomena including “Mr. Hankey’s Christmas Classics” (s03e15,1999), “A Ladder to Heaven” (s06e12, 2002), “Good Times with Weapons” (s8e01), “Whale Whores” (s13e11), “City Sushi” (s15e6), “Ginger Cow” (s17e6, 2013), and “Tweek x Craig” (s19e6, 2015).

[ii] An updated list of South Park’s ongoing controversies can be retrieved at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/South_Park_controversies#Criticism_and_protests.

[iii] Together with Chinpokomons, the Gremlins seem to share several features with Pokémon creatures. In the film series, these furry critters are imported to the US from an East Asian trinket store based in Chinatown, where they are called “mogwai” (in Cantonese, “devil”). Like Pokémon, they have kawaii features, get stored in little boxes, and can transform, fight, and reproduce themselves. Furthermore, similar to Pikachu, a popular media mix of collectible toys, videogames, novels, and spin-offs is based on Gizmo, the iconic leading mogwai of the saga.

[iv] The episode which provoked seizures was “Dennō senshi Porygon” (s01e38, 1997). The complete Tv Tokyo production and broadcasting animation guidelines can be accessed at https://www.tv-tokyo.co.jp/kouhou/guideenglish.htm. For an academic bibliographic coverage of the Pokémon Shock see https://www.animemangastudies.com/2015/10/20/seizures-induced-by-pokemon-episode-a-bibliography/. Notably, the P-shock incident was first parodied by The Simpsons in “Thirty Minutes Over Tokyo” (s10e23), aired on May 16, 1999.