Introduction

Historically, animated cartoons and movies have been used as ‘propaganda’ in war (Roffat 2011). Some animated films, however, contribute to conveying an anti-war pacifist point of view (Takai 2011). As such, the film Porco Rosso (1992) can be categorized as “anti-war propaganda” (Okuda 2003, p. 144). Although Miyazaki has been attracted by seaplanes designed and manufactured during the period between the First World War and the Second World War (Kiridoshi 2008, p. 72), this film conveys the important memory of war, especially the interwar era and the post-Cold War world. Indeed, in an interview just before the release of Porco Rosso, Miyazaki stated that the film is relevant to the Gulf War, and referred to the Yugoslav Wars as ethnic and nationalistic conflicts (Miyazaki 1996, p. 519; Miyazaki 2002, p. 95). In this context, the film forwards Miyazaki’s anti-war message.

This paper examines Porco Rosso (Kurenai no Buta), which is based on 15 pages of Hikotei Jidai (The Golden Age of the Flying Boat), a comic created by Hayao Miyazaki and released in the animation journal, Model Graphics, No.14-16 in 1990 (Kiridoshi 2008, p. 72). A synopsis of the comic story is literally “typed” at the beginning of Porco Rosso, as follows: “This motion picture is set over the Mediterranean Sea in an age when seaplanes ruled the waves. It tells a story of a valiant pig, who fought against flying pirates, for his pride, for his lover, and for his fortune. The name of the hero of our story is Crimson Pig.”

Scholarship on this film has focused on issues of “war and peace,” especially in terms of the “non-war” (hisen) message (e.g. Okuda 2003). Similarly, Kazami et al (2002), among others, (Kano 2006; Kiridoshi 2008) provide some answers to the central question of the film: Why did Porco turn into a pig? The primary reason is that he was traumatized by the war. Building on Kazami et al’s work, this paper attributes the reason that Porco became a pig to the following three aspects: “man, the state and war” (Waltz, 1959). According Kenneth Waltz, theorist of international politics, the causes of war occur on three levels: individual, domestic, and international. Like Waltz, I argue here that Porco became a pig because he hates the following three factors: man (egoism), the state (nationalism) and war (militarism). Accordingly, my analysis of Porco Rosso is situated in the framework of peace research and international relations, such as non-killing philosophy, soft power/hard power, and conflict prevention/conflict resolution.

Methodology

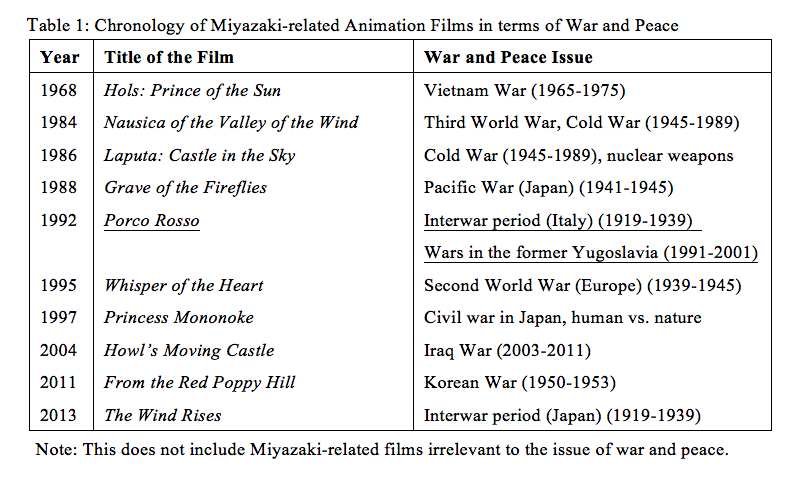

In the field of animation studies, animation films by Studio Ghibli have been frequently analyzed as a case study. Ghibli animation films are “often considered as artistic productions, both entertaining and meaningful” (Gan 2009, p. 36). There are a large number of publications on the Studio Ghibli’s films, particularly those directed by Hayao Miyazaki. Nobuyuki Tsugata (2004), for instance, examined Miyazaki’s works in comparison with the animated cartoons of Osamu Tezuka, the creator of Astro Boy (1963). Miyazaki’s films also have been discussed compared with Disney animation. For instance, Kaori Yoshida (2011) offered a comparative analysis on Disney’s Pocahontas (1995) and Ghibli’s Princess Mononoke (1997) in terms of national identity. Moreover, some scholars (e.g. Kano 2006; Kiridoshi 2008) provided comprehensive thematic or structural analyses of Miyazaki’s films. However, earlier studies on Miyazaki animation, or Miyazaki-related animation films, do not necessarily focus on the issue of war and peace. Therefore, this paper offers an analysis of Miyazaki-related animation films in terms of war and peace (Table 1).

Although the Miyazaki-related films in Table 1 do not directly deal with war themselves, all of them are related to war and peace to a certain extent. Hols: Prince of the Sun (1968) was released in the middle of the Vietnam War (1965-1975) and some combat scenes of the film represent the war. Miyazaki was involved as an animator in the creation of the film with director Isao Takahata, a friend and colleague.

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984) is a masterpiece, and the film reflects the international politics during the Cold War. The Giant Warrior (kyoshinhei) that caused an apocalyptic war, or the Seven Days of Fire, functions as a symbol of nuclear weaponry. The confrontation between Pejite and Tolmekia, the two powerful countries in the story can similarly be regarded as reflection of the Cold War bipolar structure (Akimoto 2014a). Laputa: Castle in the Sky (1986) was also created during the middle of the Cold War. The number of nuclear warheads in the world reached its peak in the mid-1980s, and the military technology of the legendary castle, Laputa, also symbolizes nuclear weapons. In this film, the word, “peace” is used only one time by Muska, who tries to conquer the world by taking possession of Laputa’s military technology. Obviously, this is a “political satire” by Miyazaki (Akimoto 2014b). Grave of the Fireflies (1988), a fictional film about a Japanese boy and his little sister at the end of the Pacific War (1941-1945), was not directed by Miyazaki but instead by Isao Takahata, another Studio Ghibli director (Akimoto 2014c), but reflects similar anti-war sentiment.

In the post-Cold War context, Miyazaki produced Porco Rosso (1992) which depicts the interwar period (1919-1939) of the Adriatic Sea in conjunction with the Yugoslavian War (1991). Miyazaki contributed to the creation of Whisper of the Heart (1994) that has a passing reference to the Second World War (1939-1945). Princess Mononoke (1997) deals with Japanese civil war as well as confrontation between humans and animals. Howl’s Moving Castle (2004) and the latest film, The Wind Rises (2013) are related to the 2003 Iraq War, and the Asia Pacific War (1931-1945) (Akimoto 2014d; Akimoto 2014e). Thus, the films in which Miyazaki or Studio Ghibli is involved can be analyzed from a perspective of peace research (peace studies), an academic field which examines causes of war and conditions for peace. While ethical and legal issues need to be carefully taken into consideration when teaching Japanese animation (McLelland 2013), Studio Ghibli animation films can be useful as educational materials at the university level (Yonemura 2003, p. 10), particularly in the fields of both peace research and peace education. From the perspective of peace research, Porco Rosso makes a particularly rich case study, particularly because Miyazaki won the best feature film award in the 1993 Annecy International Animation Film Festival (Annecy.org 2013). Due to the award, which is one of the most internationally prestigious animation film festivals, the film was internationally acclaimed, and Miyazaki characterized as “Walt Disney Nippon” (Christin 1997, p. 184).

Most reviews of and scholarship on Porco Rosso tend toward general analysis, lacking a specific focus on war and peace (e.g. Animage 1992, 2011; Kazami et al. 2002; Okuda 2003; Kano 2006; Kiridoshi 2008). Moreover, Miyazaki himself has made similar comments on his own work (Miyazaki 1996, 1997, 2013). Yet, none of the earlier studies of the film have investigated them from a perspective of peace research. In order to examine Porco Rosso, which conveys a similar anti-war message to The Wind Rises (Kaze Tachinu) (2013), which narrates Japan’s interwar period and war responsibility (Akimoto 2013a), this paper employs an interdisciplinary approach which combines peace research with animation studies. As an analytical method, this paper combines keyword analysis described above with sequence analysis of character’s lines as well as historical events. The sequence analysis is useful tool to examine timeline sequence (Abbott 1995) and it is applicable to film studies with a particular focus on character’s lines in historical context. Accordingly, the five main characters as well as historical background of this film need to be overviewed in this section.

First, the hero of this film is a pig, Porco Rosso who flies in his crimson seaplane, SAVOIA S-21. As a bounty hunter, he cracks down on Aero Viking (Sky Pirates) in the Adriatic Sea after the First World War. He used to be a human (Marco Paggot) and the ace pilot of the Italian Air Force, but he decided to leave the army after the war and cursed himself, turning into a pig. As I outline below, Porco was traumatized by his experiences in the war (Animage 2011, p. 35-37). Second, Madam Gina, a childhood friend of Porco and a madam of Hotel Adriano, is one of the two heroines of this film. In the film, it is said that pilots in the Mediterranean Sea tend to fall in love with her and visit Hotel Adriano for her song. She was married to three pilots who were all members of the Flying Club she organized as a child, but all of them died in the Great War, or in a flight accident. Gina is in secret love with Porco and vice versa (ibid, p. 54-57).

Third, Fiyo Piccolo, the other heroine, is a 17-year old female mechanic and the granddaughter of Master Piccolo. She repairs Porco’s seaplane and develops an adolescent infatuation with him (ibid, 43-45). Fourth, Donald Curtis, an American pilot and Porco’s rival, is hired by Aero Viking to fight against Porco. He is a competent pilot and has an ambition to first become a Hollywood movie star, and then US President afterwards. Curtis falls in love with Gina at first sight and falls for Fiyo next (ibid, pp. 48-51). Fifth, the Mamma Aiutos, one of the largest Aero Vikings in the Adriatic Sea, steals and kidnaps for a living after the First World War (ibid, p. 63-65). This study examines the five character’s lines in the following historical context as demonstrated by Table 2 below.

At a macro level, the chronology of the interwar period as the historical background for the film needs to be taken into consideration, as this background is crucial in understanding the content of this film. At a micro level, key scenes and main characters’ lines of the film will be examined. This is also imperative to comprehend the implications of the film for the issue of war and peace. The sequence of the nine most significant scenes in the film are as follows:

1) Porco’s “Non-Killing” Policy: Battle with the Mamma Aiutos

2) Gina’s “Soft Power” and “Peaceful Conflict Prevention”

3) Gina’s Life in War and Peace

4) Porco’s Antipathy towards the State and War

5) Fiyo and Repair of Porco’s Fighter Plane

6) The Pig and the Italian Air Force: “Better a Pig than a Fascist”

7) Fiyo’s “Soft Power” and “Peaceful Conflict Resolution”

8) The War and the Spell: Why Did He Turn Into a Pig?

9) Porco’s “Non-Killing” Philosophy in the Final Battle

The main characters’ dialogue in these nine sections accordingly constitute the primary source to be carefully investigated, in combination with my earlier argument, and relevant publications as secondary source in the context of the interwar period. The sequence analysis of the film and characters’ lines will be examined by using keywords in peace research and international politics.

Findings

1. Porco’s “Non-Killing” Policy: Battle with the Mamma Aiutos

The film begins with a scene in which the main character, Porco Rosso (who seems to be enjoying his vacation – drinking wine and taking a nap at a beach), wakes up with a phone call for an emergency. He works as a contract combat fighter pilot in order to crack down on flying pirates and gangs, such as the Mamma Aiutos. Although he left the Italian Army, he works for peace and security of the Adriatic Sea in place of Mussolini’s National Fascist Party. Italy was one of the member states of Security Council on the League of Nations (1920-1946), but its collective security system did not function, and eventually could not prevent the occurrence of the Manchurian Incident (1931) and the Abyssinian Crisis, or the Second Italy-Ethiopian War (1935-1936). In this way, Porco’s work in the film can be seen as police operations, to maintain peace and safety during the time period. As I will discuss, the international system is more anarchic in this age, and the police and military forces of Italy were not necessarily efficient or functional, leading to the populace in the film making a contract with Porco to crack down on flying pirates.

In the field of peace research, Glenn D. Paige (2009) examines “non-killing” as an analytical terminology. This paper, therefore, uses the term “non-killing” as a research keyword. In the first battle scene of this film, Porco demonstrates his “non-killing” policy. In order to make money, save hostages, and to keep peace on the Adriatic Sea, Porco decides to crack down on the Mamma Aiutos, but remains true to his “non-killing” principles. In the battle scene with the Mamma Aiutos, it comes to light that Porco has no intention to kill the gang. Instead, he tries to shoot their aircraft without causing serious damage to the pirates and hostages, and then demands that they should leave half the money and hostages in exchange for their lives. Although he calls a bluff saying: “Or I’ll kill all of you,” his policy is very clear early on in the film.

2. Gina’s “Soft Power” and “Peaceful Conflict Prevention”

Female characters in this film (Gina and Fiyo) were depicted as attractive and peaceful heroines. In terms of gender studies, Kuwabara (2007) sheds light on the concept of “feminism” and the meaning of the crimson color reflected in the movie. In an application of politics and international relations, Tomoko Shimizu (2004) analyzes Ghibli animation in terms of “soft power” in the post-Cold War era. The concept of “soft power” was proposed by Joseph Nye, a Harvard Professor and political scientist. As opposed to “hard power” which based on military power, “soft power” can be defined as “the ability to get what you want through attraction rather than coercion or payments. It arises from the attractiveness of a country’s culture, political ideas, and policies” (Nye 2004, p. x). In this framework, Japanese animation can be understood as Japanese “soft power,” which works to enhance Japan’s international image and attractiveness as national interest. For example, Nobuyuki Tsugata (2004) used the term “power of Japan animation” to contextualize the Japanese animation industry, which has lasted more than 85 years. Likewise, William Armour (2011) described Japanese animation and manga for learning Japanese language as “soft power pedagogy” (p. 125).

In this fashion, Gina and Fiyo, as the two main female characters, become exemplary of the concept of “soft power.” After the battle, Porco drops in the Hotel Adriano run by Madam Gina, a childhood friend. In the film, it is stressed that Gina’s charismatic beauty and elegance prevents violent conflict by air pirates from occurring around her hotel. For instance, Donald Curtis, an American air fighter as a rival of Porco, says: “She is quite a woman… Air pirates and bounty hunters alike leave their quarrels outside.” The reason why the flying gang never fights near the Hotel Adriano can be inferred by the fact that the gang know that Gina lost her husband in WWI, which I will discuss in the next section.

When tension builds between Porco and a drunken gang, Gina swiftly intervenes and prevents confrontation from escalating. Gina says to the gang: “Quite a distinguished gathering! You boys must be planning something… Always glad to see you, but no war games here, OK?” One of the gang responses: “We know, Gina. We don’t work within 50 kilometers of here”. Another gang continues: “We’re even polite to the pig!” And then Gina says: “That’s my boys.” This scene reflects Gina’s charm as “soft power” in contrast to gang’s “hard power” results in peaceful conflict resolution. As such, conflict resolution can be divided into the following four phases: 1) preventive diplomacy (conflict prevention), 2) peacemaking (peace enforcement), 3) peacekeeping, and 4) peacebuilding, as proposed by Boutros Ghali, the former UN Secretary General, in his “An Agenda For Peace” (United Nations 1992). In application of the process of conflict resolution, Gina’s approach in the Hotel Adriano can be categorized as “preventive diplomacy” (conflict prevention) by her soft power.

3. Gina’s Life in War and Peace

In opposition to her otherwise peaceful and graceful characteristics, Gina’s life seems to be swayed by the time period, especially the war. Gina literally hates war (Isaka 2001, p. 156). The film implies that Gina lost her first husband because of the First World War. The war was triggered by the assassination of Franz Ferdinand of Australia, the heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary, at Sarajevo on 28 June 1914. About one month later, Austria-Hungary as an ally of Germany declared a war on Serbia, a key ally of Russia. The two blocks involved the entire Europe and led to the Great War. Originally, Italy was a part of the Central Powers (Triple Alliance) with Germany and Austria-Hungary, but it eventually joined the Allies (Triple Entente) led by the United Kingdom, France, and Russia. This was how the Italian Air Force had to fight against the Austria-Hungary Force in the Adriatic Sea (Matsuki 2013, p. 46).

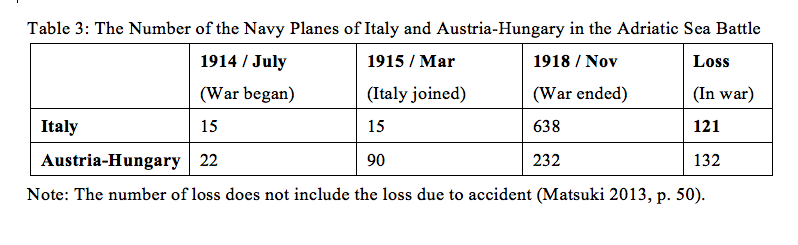

At the beginning of the First World War, the number of combat planes of the Italian Navy was 15, and that of Austria-Hungary was 22. When Italy declared war against Austria-Hungary on 23 May 1915, Italy possessed only 15 combat airplanes, whereas Austria-Hungary already had about 90 warplanes ready to attack Venice.

At the end of the war, the total number of the Italian Navy was as many as 1,630, whereas that of Austria-Hungary was around 650. During the war, Italy lost 121 fighter planes and destroyed 132 Austrian-Hungarian combat planes. The most important base for the Italian Navy was Venice, which was assaulted 42 times and 1,037 bombs were dropped on the city. The number of the combat planes involved in the war in the Adriatic Sea can be shown as Table 3.

The death toll of Italian pilots from the battle in the Adriatic Sea can be inferred by the number of the loss, and Gina’s husband could be included. Gina has married two other pilots who were also killed in combat. She tells Porco: “One died in the war, one in the Atlantic, and the third in Asia.” Porco asks: “They found him?” And Gina replies: “I got a call today. They found his remains in Bengal. It’s been three years. I’ve got no more tears left.” To which Porco replies: “The good ones always get killed.” Their conversation indicates that Gina’s husbands died due to flight accidents or fell in the line of duty for the Italian Air Force, which Porco left. This is the reason why Gina hates “war” and, moreover, tries to stop Porco from going to the air fight.

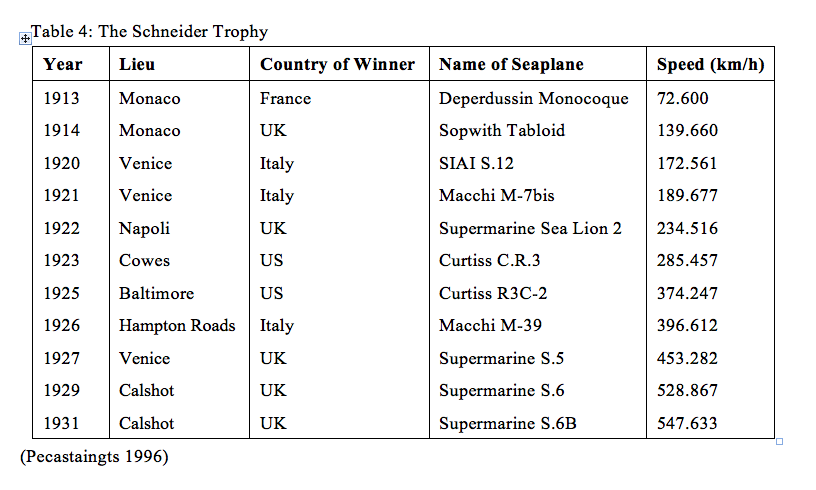

Gina’s second husband was likely a similarly capable pilot who possibly met with an accident during the flight for adventure or international seaplane race, such as the so-called “Schneider Trophy. ” The award was named after Jacques Schneider, a French industrial manager, and the races were held from 1913 to 1931 (Table 4).

As Table 4 demonstrates, Italian pilots won the Schneider Trophy three times, and six races took place in Italy itself. Given Porco’s flying skill as the “ace” of the Italian Air Force, it is entirely likely that Porco or the other members of the Flying Club organized by Gina might have participated in the Schneider Trophy. According to Pierre Pecastaingts (1996), there were no casualties in the race of the Schneider Trophy, training for the races led to fatal accidents, killing five Italian pilots. Accordingly, it is possible that Gina’s second husband met flight accident in preparation for a contest not unlike the Schneider Trophy. Or they might have died in the flying training or military mission of the Italian Air Force. In either scenario, Gina’s wartime and peacetime experiences have been influenced by airplanes, and contributes to her fears for Porco.

4. Porco’s Antipathy towards the State and War

Although Porco “fights” for bounty money as a seaplane pilot, he demonstrates antipathy towards the state (nationalism/fascism) and militarism (war). After he left the Hotel Adriano, he goes to a bank. A military parade full of national flags on tanks with a militaristic music took place on the street beside the bank. When Porco enters the bank to withdraw some money, a bank clerk mentions that it “must be nice to make that much money… How about making a contribution to the people with a Patriot Bond?” To which Porco replies, “I’m not a person.” The “patriot bond” is meant to be a war bond, necessary to prepare and wage wars by the Italian government. Here, Porco clearly opposes financial contribution to fascism and militarism. Also, this scene reminds Japanese audience of Japan’s response to the 1990 Gulf Crisis, during which, the Japanese government was reluctant to making financial contributions to the US-led multinational forces (Akimoto 2013b).

After he leaves the bank, Porco walks down to buy weapons for his seaplane. In accordance with his non-killing policy, Porco purchases only light weapons, so a young weapon trader asks Porco to buy more strong weapons saying: “Just regular bullets? Not high-explosives, or armor-piercing?” Yet, Porco turns him down, replying: “Listen, kid. We’re not fighting a war out there. See you.” Immediately thereafter, the young trader asks his boss: “Hey. Boss… How is war different from bounty hunting?” And the boss sarcastically replies that: “War profiteers are villains. Bounty hunters are just stupid.” These scenes regarding “war bond” and “military weapons” foreground Porco’s hatred towards nationalism (fascism) and militarism, and works to highlight Miyazaki’s own anti-war pacifism and his viewpoint on the 1990 Gulf Crisis and the 1991 Gulf War.

5. Fiyo and Repair of Porco’s Fighter Plane

When Porco flies to go to have his seaplane fixed at the Piccolo’s, Curtis, an American seaplane pilot hired by the Mamma Aiutos suddenly attacks Porco. Yet, Porco tries to avoid one-on-one fight mainly because of the engine trouble, but fundamentally due to his non-killing policy. This is how Curtis succeeds in damaging Porco’s seaplane and it leads to a major repair at the Piccolo’s. Fiyo, Piccolo’s granddaughter, designs and plans the repair and rebuilding of Porco’s seaplane. That only female workers who are related to Piccolo are involved in the creation of the new plane is suggestive of the effects of the Great Depression, wherein men travelled for work outside the town or to join the military.

6. The Pig and the Italian Air Force: “Better a Pig than a Fascist”

Porco’s anti-fascist attitude is reflected by the fact that Porco Rosso also makes reference to Casablanca (1942), an American romantic drama, which portrays the fight against the Nazis during the Second World War as “war propaganda” (Okuda 2003, p. 137-144). Similarities between the two films include characters, but the purpose of Casablanca is considered to justify US participation in the war in Europe (ibid, p. 140), whereas that of Porco Rosso is oppose killing and war in general. In this regard, its fundamental political message of the film is not only anti-fascism, but also anti-war pacifism. When Porco watches a movie at a theatre, Ferrarin, Porco’s old friend in the Italian Air Force, warns that there are warrants out on Porco for “treason, illegal entry… decadence, pornography and being a lazy pig.” Ferrarin suggests that Porco should come back to the Air Force before the authorities seize his plane. However, Porco flatly declines this offer, saying: “Better a pig than a Fascist.” In response, Ferrarin warns again to “Be careful. They won’t bother with a court of law.” This scene is telling, in that Porco, who used to be a war hero, decided to become and remain a pig because he did not want to be a fascist who supported nationalistic militarism during that time.

After their conversation in the theater, as Ferrarin mentioned, Porco and Fiyo are being tailed by the Fascist Secret Police. Fiyo insists that she needs to accompany Porco as a mechanic, but Porco opposed her plan at first. Yet, Fiyo persuaded Porco to come along with him, and Porco finally says: “Take out the right machine gun. I don’t care how small your bottom is. It won’t fit between them.” This implies that in addition to his anti-fascist stance, Porco is also a feminist who respects women, at the sacrifice of weapons on his airplane. When Porco and Fiyo are about to take off, the Fascist Secret Police shoot the plane, and Porco discharges a machine gun at them as warning shots, but does not intend to kill them. These scenes are an additional reflection of Porco’s “non-killing” philosophy, is situated in Miyazaki’s anti-war pacifism.

7. Fiyo’s “Soft Power” and “Peaceful Conflict Resolution”

The Mamma Aiutos and other air pirates ambush and take Porco and Fiyo as hostages at Porco’s hideout. When the pirates say they are going to destroy Porco’s fighter plane, Fiyo, as a designer of the plane, strongly objects. She makes an eloquent speech to the boss of the Mamma Aiutos about how brave and proud seaplane pilots are, and how noble and respectful the gang should be. Her attractiveness as Piccolo’s chief plane designer, as well as her peaceful means of conflict resolution, save the plane in addition to Porco’s life. In place of the Mamma Aiutos, Curtis says that he will have a one-on-one battle with Porco. Again, Miyazaki places an emphasis on the soft power of female characters, in brokering peaceful conflict resolution. Where Gina showed her soft power for “conflict prevention” as preventive diplomacy, Fiyo’s courageous approach led to the peaceful and successful ‘conflict resolution’ which prevents confrontation from escalating into violence. This is how Miyazaki makes audience remember the importance of peaceful conflict resolution based on a “non-killing” philosophy.

8. The War and the Spell: Why Did He Turn Into a Pig?

The night before the rematch with Curtis, Fiyo asks Porco why he turned into a pic, but he does not directly answer her question. According to Fiyo, her father was in the same unit as a Flight Lieutenant Marco Paggot, or, Porco when he was still human and the ace pilot of the Italian Air Force. Fiyo’s favorite story about the war is that Porco jumped off a cliff to rescue an enemy pilot in a war, which is indicative that Porco was an anti-war humanist long before he became a pig.

In the evening, Porco finally tells what happened and implies how he turned into a pig in the last summer of the war. This episode is one of the most important scenes in the film, according to most scholars (Kazami et al. 2002, p. 140; Kano 2006, p. 163; Kiridoshi 2008, p. 79). Porco flew with his old friend Berlini, who had just married two days before the final patrol over the Adriatic. During the flight, they were attacked by Austrian fighter planes. Porco did not have enough leeway to assist Berlini, and turned out to be the only survivor of the battle. Porco was so exhausted and traumatized that he hallucinated and saw other dead pilots going up to the cemetery of fighter planes. Berlini was one of Gina’s husbands, and Porco was the best man at their wedding.

The film implies that Porco could not forgive himself for forsaking Berlini and this is one of the main reasons why he decided to cast a spell to turn himself into a pig. It is also understandable that he came to hate humans, the government, and the war that killed his most of his friends and cursed his life. Through his experience, he actually saw that war makes people ugly, egoistic and inhumane. In short, the war, on the basis of egoism, nationalism and militarism, traumatized Porco so much that he decided to turn himself into a pig. Japanese people tend to regard pigs as uglier than any other animal, but ironically, Miyazaki in the film strongly suggests that humans sometimes can be uglier than pigs.

9. Porco’s “Non-Killing” Philosophy in the Final Battle

Even in the final battle wagering Fiyo, Porco sticks to his “non-killing” principle and does not attempt to kill Curtis. Indeed, the boss of the Mamma Aiutos offers commentaries that: “The Pig’s not a killer,” and that “The damn fool thinks this isn’t war!” Porco’s strategy is to let Curtis shoot first until he runs out of bullets. Owing to the “barrel roll” flying manoeuver which made Porco “the Ace of the Adriatic,” Porco gets a chance to shoot Curtis’s plane, but he still does not discharge the machine gun. Porco only waits for an opportunity to place a few non-fatal shots into the engine so that he does not need to take Curtis’s life.

After Porco and Curtis run out of bullets, they end up in physical altercation. This scene could be considered as animated violence, as Princess Mononoke (Mononoke Hime) (1997) is often criticized as full of “violence and bleeding” (Kusanagi 2003, p. 266-267), but at the same time, it illustrates the foolishness of fighting. At the end, the fight itself turns out to be more of a sport (boxing match) than actual violence or bloodshed. Eventually, Porco wins the boxing match and Gina comes to announce “ceasefire” noting: “Ok, the party is over. The Italian Air Force is coming. Get out of here, everyone.” Again, it is emphasized that Gina, on the basis of her soft power, takes leadership for the ceasefire and prevents the gangs from triggering unnecessary collateral conflicts after the battle. As was the case at the Hotel Adriano, Gina’s role here is conflict prevention based on preventive diplomacy. Thus, Miyazaki stresses the significance of peaceful conflict resolution as “non-killing” through to the end of the film.

Conclusion

It has been emphasized and confirmed that Porco became a pig not only because of war (militarism) and the state (nationalism/fascism), or but also because of negative human nature (egoism). This is how he came to detest being a human. In addition, Porco’s “non-killing” philosophy has not changed until the very ending of this film. This film also stresses “soft power” of Gina and Fiyo in the conflict prevention, conflict resolution and ceasefire.

In the epilogue of the film, even after the failure of the crackdown by the Italian Air Force, Porco never turns up in front of Fiyo. Instead, Fiyo becomes good friends with Gina as they underwent the subsequent war and turmoil. Curtis became a movie star in the United States and other flying pirates still visit the Hotel Adriano. It is not a gloomy epilogue, but what happened to Porco still remains a mystery.

Historically, it is logical to infer that Fiyo and Gina survived the Second World War. Porco’s antipathy towards fascism and war has been consistent throughout this movie, so it is unlikely that Porco would return to the Italian Air Force during the this conflict. However, according to Miyazaki, Porco is supposed to be the fourth husband of Gina (Kano 2006, p. 163) and it is suggested that Porco could be involved in the war not for his country, but for Gina, Fiyo and his friends, and this might be the reason why Porco never shows up in the epilogue narrated by Fiyo. In conclusion, through the comical and romantic animated storyline, this movie conveys Miyazaki’s antiwar pacifism, non-killing philosophy, and the memory of war.

This research was originally presented as “War and Peace in Japanese Animation: Miyazaki Anime’s Message for Peaceful Coexistence” at the Asia Pacific Peace Research Association (APPRA) conference organized by Thammasat University in Bangkok, Thailand in November 2013.

Daisuke Akimoto is an Assistant Professor at the Soka University Peace Research Institute, Soka University, Japan.

References

Abbott, Andrew. 1995. “Sequence Analysis: New Methods for Olds Ideas.” Annual Review of Sociology 21: 93-113.

Akimoto, Daisuke. 2013a. “Miyazaki’s New Animated Film and Its Antiwar Pacifism: The Wind Rises (Kaze Tachinu).” Ritsumeikan Journal of Asia-Pacific Studies 32: 165-167. Available at

http://www.apu.ac.jp/rcaps/uploads/fckeditor/publications/journal/Volume32_op.pdf

Akimoto, Daisuke. 2013b. Japan as a “Global Pacifist State”: Its Changing Pacifism and Security Identity. Bern: Peter Lang AG International Academic Publishers.

Akimoto, Daisuke. 2014a. “Learning Peace and Coexistence with Nature through Animation: Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind.” Ritsumeikan Journal of Asia Pacific Studies 33: 54-63. Available at

http://www.apu.ac.jp/rcaps/uploads/fckeditor/publications/journal/RJAPS33_6_Akimoto2.pdf

Akimoto, Daisuke. 2014b. “Laputa: Castle in the Sky in the Cold War: As a Symbol of Nuclear Technology of the Lost Civilization.” Electronic Journal of Contemporary Japanese Studies (EJCJS) 14 (2). Available at

http://www.japanesestudies.org.uk/ejcjs/vol14/iss2/akimoto1.html

Akimoto, Daisuke. 2014c. “Peace Education through the Animated Film ‘Grave of the Fireflies’: Physical, Psychological, and Structural Violence of War.” Ritsumeikan Journal of Asia Pacific Studies 33: 33-43. Available at

http://www.apu.ac.jp/rcaps/uploads/fckeditor/publications/journal/RJAPS33_4_Akimoto.pdf

Akimoto, Daisuke. 2014d. “Howl’s Moving Castle in the War on Terror: A Transformative Analysis of the Iraq War and Japan’s Response.” Electronic Journal of Contemporary Japanese Studies (EJCJS) 14 (2). Available at

http://www.japanesestudies.org.uk/ejcjs/vol14/iss2/akimoto.html

Akimoto, Daisuke. 2014e. “War Memory, War Responsibility, and Anti-war Pacifism in Director Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises (Kaze Tachinu).” Soka University Peace Research 28: 45-72.

Animage. 1992. Eiga: Kurenai no Buta Guide Book (Film: Porco Rosso Guide Book). Tokyo: Tokumashoten.

Animage, ed. 2011. The Art of Porco Rosso. Tokyo: Tokuma Shoten.

Annecy.org archives. 2013. “1993 Award Winners: 1993 – Award for Best Feature Film, Kurenai no Buta”.

http://www.annecy.org/about/archives/1993/award-winners/film-index:f930184 (accessed 24 October 2013).

Armour, William S. 2011. “Learning Japanese by Reading ‘Manga’: The Rise of ‘Soft Power Pedagogy’.” RELC Journal 42 (2): 125-140.

Christin, Philippe. 1997. “Yoroppa wa Ikani Miyazaki Hayao o Juyo shitaka (How Europe Accepted Hayao Miyazaki).” Yuriika (Eureka) 29 (11). (August 1997): 178-185.

Gan, Sheuo Hui. 2009. “To Be or Not to Be: The Controversy in Japan Over the ‘Anime’ Label.” Animation Studies Online Journal 4: 35-43.

Isaka, Jujo. 2001. Miyazaki Hayao no Susume (Hayao Miyazaki Fantasy World). Tokyo: Taiyoshuppan.

Kano, Seiji. 2006. Miyazaki Hayao Zensho (The Complete Miyazaki Hayao). Tokyo: Film Art-Sha.

Kazami, Hayato, and Tokyo Anime Kenkyukai. 2002. Sutajio Jiburi no Himitsu (Secrets of Studio Ghibli). Tokyo: Data House.

Kiridoshi, Risaku. 2008. Miyazaki Hayao no Sekai (World of Hayao Miyazaki). Tokyo: Chikuma Shobo.

Kusanagi, Satoshi. 2003. America de Nihon no Anime wa Domiraretekitaka? (How Has Japanese Animation Been Viewed in the United States). Tokyo: Tokuma Shoten.

Kuwabara, Noin. 2007. Miyazaki Hayao “Kurenai no Buta”-Ron: Gender-ron Kara (An Analysis of Porco Rosso by Hayao Miyazaki: From the Perspective of Gender Studies). Tokyo: Shinpusha.

Matsuki, Yuji. 2013. “Adoriakai Kokusen” (The Air Battle in the Adriatic Sea). In Hayao Miyazaki. 2013. Hikotei Jidai (The Golden Age of the Flying Boat). Tokyo: Dainihonkaiga, 46-50.

Miyazaki, Hayao. 1996. Shuppatsuten 1979-1996 (Starting Point 1979-1996). Tokyo: Tokuma Shoten.

Miyazaki, Hayao. 2002. Kazeno Kaeru Basho: Nushika kara Chihiro madeno Kiseki (The Place Wind Returns: From Nausica to Chihiro). Tokyo: Rockin’on.

Miyazaki, Hayao. 2013. Hikotei Jidai (The Golden Age of the Flying Boat). Tokyo: Dainihonkaiga.

Nye Jr., Joseph S. 2004. Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics. New York: Public Affairs.

Okuda, Koji. 2003. “Kurenai no Buta” to “Hisen”: 9/11 Iko (“Porco Rosso” and “Non-War” in post-9/11). In Miyuki Yonemura ed. Jiburi no Mori e (Towards Forest of Ghibli). Tokyo: Shinwasha, 118-151.

Paige, Glenn D. 2009. Nonkilling Global Political Science. Honolulu: Center for Global Nonkilling.

Pecastaingts, Pierre. 1996. The Schneider Trophy and the Vintage Seaplane.

http://www.hydroretro.net/indexen.html (accessed 10 October 2013).

Roffat, Sebastien. 2011. Anime to Propaganda: Dainiji Taisenki no Eiga to Seiji (Animation and Propaganda: Films and Politics in the Second World War). Tokyo: Hosei University Press.

Shimizu, Tomoko. 2004. “Nezumi to Monster: Posuto Reisen to Soft Power no Chiseigaku (Mouse and Monster: Soft Power Geopolitics in the post-Cold War).” In Yuriika (Eureka: Poetry and Criticism) 36 (13). (December 2004): 194-204.

Studio Ghibli. 1992. Porco Rosso (Kurenai no Buta) (DVD).

Studio Ghibli. 1997. Princess Mononoke (Mononoke Hime) (DVD).

Takai, Masashi ed. 2011. “Hansen” to “Kōsen” no Popular Culture: Media, Gender, or Tourism (Pacifism and Militarism in Popular Culture: Media, Gender, or Tourism). Kyoto: Jimbun Shoin.

Tsugata, Nobuyuki. 2004. Nihon Animation no Chikara (Power of Japan Animation). Tokyo: NTT Publication.

United Nations. 1992. “An Agenda for Peace: Preventive Diplomacy, Peacemaking and Peace-keeping.” 17 June 1992. http://www.unrol.org/files/A_47_277.pdf (accessed 6 August 2014).

Waltz, Kenneth. 1959. Man, the State, and War: A Theoretical Analysis. New York: Columbia University Press.

Yonemura, Miyuki. 2003. ed. Jiburi no Mori e (Towards Forest of Ghibli). Tokyo: Shinwasha.

Yoshida, Kaori. 2011. “National Identity (Re) Construction in Japanese and American Animated Film: Self and Other Representation in Pocahontas and Princess Mononoke.” Electronic Journal of Contemporary Japanese Studies (EJCJS). 30 September 2011. Available at http://www.japanesestudies.org.uk/articles/2011/Yoshida.html

(accessed 25 October 2013).

© Daisuke Akimoto

Edited by Amy Ratelle

![]() To download this article as PDF, click here.

To download this article as PDF, click here.