Ganime is a new corporate project to develop the features of selective animation to provide a more flexible category of anime. Ganime was created jointly by Toei Animation and the publisher Gentosha. The overall project is to promote auteurism in animation by encouraging creators to have the freedom to exercise their imagination instead of conforming to the predetermined norms of the anime industry. The Ganime project also intends to liberate the artists’ creativity through collaboration among painters, novelists, musicians and film directors.

“Ga” is written with a character meaning “painting,” in their usage it is not restricted to any particular method but could be oil painting, ink painting, wood block printing, photography or even clay models; “nime” is written with katakana as a shortened form of “anime.” As the project name indicates, Ganime stresses the value of the drawing by the artists, treating them as establishing the core to which words and music are integrated to create a new form of expression.

At time of writing, fourteen Ganime titles have been released since the project was launched at the end of May 2006. Each work exhibits a different drawing technique, visual style and represents various genres. The Ganime Project also aims to incorporate works that employ different materials besides drawn animation. Most works have adapted noted examples of classic and contemporary literature and music to enrich the narrative element.2 Ganime tends to be character-based, slower in pace and rendered with less motion than usually found in anime. Ganime has been introduced to the public as “the art of slow animation.”3 The works are being released directly on DVDs without prior showing on television or in theatres. Ganime works vary in length; the shortest being seventeen minutes, and the longest forty minutes, while most are between twenty to thirty minutes.

Tezuka’s Mushi Productions and Ganime Project

My interest in the Ganime project was triggered by the resemblance of their basic concept to what Tezuka Osamu envisioned in his works with Mushi Productions in the 1960s and early 1970s. Tezuka is widely known for his early animated television series such as Tetsuwan Atomu (Astro Boy). Yet, he and the Mushi Productions staff also released a handful of short experimental animated films and three adult-oriented theatrical released animated films in Japan – Thousand and One Nights (1969), Cleopatra (1971) and Kanashimi no Belladonna (1973), which pioneered the possibility of animation as an entertainment for adult audiences in the early 1970s. Although not all of these works gathered attention, or achieved great commercial success, (indeed they have often been overlooked), their artistic creativity and the method of marketing are historically significant. As Japanese animation scholar Tsugata Nobuyuki points out, Tezuka and Mushi Productions have had an indispensable influence on shaping the fundamental characteristics of today’s Japanese anime. Tsugata even suggests that Miyazaki Hayao and Oshii Mamoru, leading figures in Japanese animation today, built their styles and formats on the foundation of the commercial anime that Mushi Pro inaugurated.4

Even though he died two decades ago, Tezuka is still a highly celebrated figure in Japan today. Many animation text books and articles continue to emphasize how he and Mushi Productions matured the use of simplified expression (limited-cel animation) and complex narrative structures in manga and in animated films. These developments helped pave the way for Japanese anime to flourish in the succeeding decades. Ironically, it is not uncommon to find Tezuka and Mushi Productions blamed for the very same reasons, especially by animators from orthodox studios who had been trained to emulate animation from the Disney Studio. They considered Tezuka’s animation to be poorly done, as the job of an animator was supposedly to employ a large number of cels to depict motion but not to move the drawings themselves.5 Moreover, these critics often complained that Tezuka and his studio have established a low parameter for wages and aesthetics which still sabotage the Japanese animation industry.6

Today, however, such simplified expressions are common in Japan, as several generations have grown up with animated series on television where simplified expressions are standard. In addition, the international commercial success of anime in recent years has also increased their confidence that these expressions are effective, possessing a different aesthetic from the so-called full animation. It is this particular environment of Japanese anime that allows Toei Animation-Gentosha to come up with the Ganime project. It foregrounds the beauty found in the restriction of motion, suggesting it can be viewed as a modern version of kamishibai (paper drama).

Both Tezuka and the Ganime creators share the similar idea of assembling a group of artists to experiment with new techniques in order to establish a platform to restore auteurism for creators. Additionally, Tezuka and Ganime creators chose a similar approach to producing their works. The need to economize motion for Tezuka and Mushi Productions was mainly driven by their economic constraints that forced them to develop an aesthetics approach to this new mode of animation. Ganime creators view the engagement of stillness or focused motion as a stylistic choice that is made possible by the comparatively inexpensive techniques they employ. These creators explicitly express their confidence in the usage of minimal motion in their animated films as a means of enriching their visual performance. This attitude is very different from the apologetic tone which was so often found in Tezuka’s statements regarding the use of the restricted movement in their early animated series. Nonetheless, both were highly motivated to produce works that emphasize creative freedom, artistic individuality and regard animation as a complex entertainment medium for an adult audience that enjoys emotionally serious and thoughtful works.>

Ganime presents a striking contrast with its understanding of the possibilities that lie in selective animation. The Ganime project emphasizes the expression of a unique personal style with a quiet atmosphere, generated by its slower pace. Some Ganime works do employ computer generated techniques to ease the production process, but they are mainly employed as a tool rather than an attempt to copy popular computer graphic styles. All these qualities have made Ganime an interesting sample to investigate the current alternative state of selective animation in Japan.

The Analysis of Ganime Works

In the following section, I identify the characteristics, current status and future potential found in three Ganime works. I have chosen two examples, Fantascope ~ tylostoma and Tori no uta (The Bird Song) by the illustrator Amano Yoshitaka, well known for his connection with Oshii Mamoru’s Tenshi no tamago (Angel’s Egg, 1985), the character design for the anime Vampire Hunter D (1985), and the image design for the Final Fantasy game among others. As Ganime advertising employs Amano’s illustrations, looking at his works forms a good introduction to the overall ambition of the Ganime project. The third work examined here, Dunwich Horror and Other Stories, is directed by Shinagawa Ryo, the editor of “Studio Voice” magazine and a film director with character design and artworks by Yamashita Shohei. This work illustrates the diversity of Ganime with its use of three-dimensional mixed materials which differentiates it from other drawn animations and computer-generated imagery. Furthermore, the main creators of The Dunwich Horror and Other Stories are still in their 30s, revealing how this new generation handles focused motion and stillness in this unconventional format.

Fantascope ~ tylostoma

Fantascope ~ tylostoma (2006) is a fantasy narrative about a man who has been condemned to wander in nothingness, only being allowed to come back to earth once every seven hundred years. During his current visit, he finds that the prosperous town he had known well had been replaced by a depressing vista of destruction. In these ruins, he encounters the only surviving person, a woman who looks like a prostitute. At her request, he starts telling his story. Very soon, the woman invites him to bed. Later, a shell he found under the woman’s bed awakens a memory. She is actually the goddess whom he had fallen in love with long ago. She had agreed to let him murder her in order for him to obtain eternal life. He had attempted to kill her, yet in a few moments it had become clear that she could not be killed. Although both were disappointed, the goddess gave him eternal life and disappeared with the sea shell. Back in the present, the woman tells him that she is the one responsible for arbitrarily destroying the world and she has long been waiting for him to come back for her. The man is shocked and once again attempts to take her life. He winds her hair around her neck and tries to kill her again, and yet, she reminds him that this will not work. Finally the man asks the woman to take his life, in order to liberate him from his tortured existence. She kisses the man and slowly inhales his breath, gradually switching back to her youthful goddess appearance. She commits suicide after taking his life. In the end, we see the man being born again as a baby calling out “mother” to a woman that looks like the goddess. >

Amano Yoshitaka is the key creator in Fantascope. He takes charge of all the sumi-e (traditional ink-and-brush painting in East Asia) style drawings and the original story, although it is directed by Kimura Soichi, known for creating commercials. This work is impressive with its black-and-white sumi-e style drawings, continual narrating voices, and the musical soundtrack that accompanies the still drawings.

The opening scene shows the creator Amano Yoshitaka sitting in front of his desk narrating a fantasy about a shell that he has had since childhood. Through his monologue the viewer learns that there have been many stories told about this type of shell, dealing mostly with death and eternity. These other stories, including “The Flying Dutchman,” inspired him to create Fantascope, a narrative about a phantom ship coming and going between death and eternity.

Showing the actual creator in live-action footage, including several close-ups of his hand in the act of drawing before the narrative unfolds, creates an intriguing introduction that is reminiscent of some early animations. The famous opening sequence of Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo (1911) is a good example. McCay is first shown in live-action footage talking with his friends in a club before the camera cuts to the performance of his animated characters. This comparison to an early animation draws attention to its different attitude towards the rendering of motion. In Little Nemo, the creation of fluid motion and metamorphosis of line drawings are the eye-catcher, as shown by the phrase “watch me move.”

In Fantascope, on the contrary, stillness is used to increase the suggestiveness of the occasional motion. Most of the time, still drawings dominate each sequence. Occasionally, selected elements within these drawings such as hair, clothing or curtains in the background are animated in a subtle manner. In most cases, the audience might not consciously notice these motions, yet they may sense their existence while attentively scanning the images. Even though these creators have the technology to portray more complex action, they chose to be subtle. Indeed, besides the minimal motion, the only distinct visual effect we see is the integration of smoke and fog with life-action footage and two dimensional sumi-e paintings. This combination creates a dreamlike state located between fantasy and reality. This visual design fits the nature of the narrative. The subtle motion amid stillness seduces the viewer into enter a world opposite our everyday life that is filled with constant motion shown on the screens of computers, televisions, hand phones and many others.

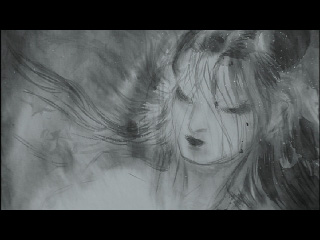

Fig. 1 & 2 – Fantascope ~ tylostoma – Sumi-e drawings are mixed with live-action footage. Image courtesy of Yoshitaka Amano, 2005/Toei Animation Co., Ltd.

Fig. 3 & 4 – Fantascope ~ tylostoma – Hair movement is the only motion found in these shots. Image courtesy of Yoshitaka Amano, 2005/Toei Animation Co., Ltd.

The use of imagery in Fantascope is distinctly different from the common pattern in anime, which tends to shorten the length of each shot generating a sense of rhythm through fast cutting. There is no sign of motion lines often used to suggest speed or motion. Most of the camera angles are from eye level, framed with a mixture of full shots, medium shots and close-ups. Occasionally, there are limited panning and zooming in camera movements. These camera movements too were also rendered in a slower pace. In other words, the viewer often gazes at a still drawing of characters while hearing a lively conversation between them. This reduction of movement is more extreme than the common anime practice of only animating the lips when a character is talking. In short, the depiction of motion in Fantascope is developed from stillness, where following the low voice of the narration with the help of music, the viewer starts to “see” the still image as a smooth depiction through the viewer’s imagination instead of focusing on literal action. In other words, the viewer is encouraged to dive into the narrative and imagine elements suggested by the imagery. Viewing Ganime is similar to the process of reading a manga, where active involvement and imagination play an important part in the whole process. There is an absence of conventional comical exaggeration as well as the festive atmosphere found in many anime. Overall, quiet mood and atmosphere pervade Fantascope from beginning to end.

Alterations of the contrast, lighting and other techniques guide the audience to focus on certain details of the drawing or stimulate the viewing process. For instance, the key color of Fantascope is grey. In the sequence where the man discovers the woman is actually the goddess he had once attempted to kill, he is showered with complex feelings. Through manipulation of the hues of the drawings, the author not only generates a subtle illusion of motion, but also successfully emphasizes the turbulent emotions of the man at this critical point. Generally, this approach is quite different from the typical image of anime where the character and scene are presented in consistent lighting and color toning.

Regarding the aspect of depth, Fantascope lacks of a geometric perspective to suggest a realistic three dimension space, like many of those recent alternative anime.7 The sense of depth is constructed through a compilation of a few different layers where the audience actually sees and feels the gap between these layers.8 Even though this openness between layers does not contribute to the verisimilitude of the image, it still effectively invites the audience to an interesting visual perspective.

The soundtrack also has a major impact on the narrative. Although the third person narration of the artist provides the audience information necessary to comprehend developments and is supported by conversation among the characters, music is used to enhance the key sentiments. Moreover, sound is also the key element in providing a lively flow to the overall narrative. Additional sound effects are used to suggest activity within the still drawing. The tone of the voices is rather different from those common in anime. The high pitch and child-like cuteness are replaced by a lower tone and a more inwardly poetic sensibility. Though, similar to many anime, Fantascope is heavily narrated and gives an impression that the work relies too much on the audio element to explain the narrative. Actually, the narrations could be further reduced and the story would still be conveyed through the stunning images.

In short, the character figure design and background design, both distinct from the so-called anime style, are the attractive features of Fantascope. The kawaii (“cute”) aspects are replaced by a more adult and artistic touch which emphasize personal style rather than copying existing anime visual norms. Thus, the use of the cyclic motion and stillness in Fantascope, while quite similar to other anime, unexpectedly generate a new impression and visual experience. Fantascope is a good example to demonstrate how old techniques were used for new effects, a creative example of selective animation.

Tori no uta

Tori no uta is an erotic fantasy of a boy’s love for a girl he met in Shizuoka, Japan, around the late 1950s and early 1960s. It begins with a boy describing a sudden downpour. He meets a very beautiful girl in an eye-catching scarlet kimono, with a little green bird standing on her shoulder, while taking shelter from the rain at her home. Even though the girl promises him they will see each other again, he fails to locate her and finally leaves the town as an adult. Fifty years pass and the man goes back to his hometown. There, he meets the girl again, unchanged despite the passage of years. The man returns to his youthful appearance, telling the girl that he wishes that they can always spend time together like this. Responding to his wish, the girl shows him a glass where there is miniature rainbow. This rainbow represents the dream of the boy. If he can tell her his thoughts, and if he is sincere, the colors of the rainbow will be released back into the sky. When all of the colors are released, the two of them will be together forever. At times, during this long narration, their imagination seems to invade reality, and reality becomes their imagination. In the end, we see the boy walking hand in hand with the girl towards an unknown future.

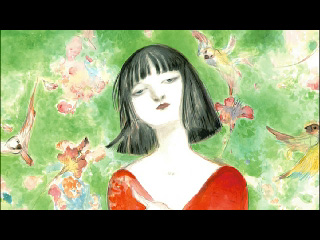

Fig. 5 & 6 – Tori no uta. Image courtesy of Yoshitaka Amano, 2005/Toei Animation Co., Ltd.

In this work Amano created both the original story and illustrations and did the direction. The first impression of this work is its selective animation and the use of striking colours against an off-white background, the dominant monologue, lyrical music and the careful placement of the narrative between fantasy and reality. The style of these illustrations shifted from his more western influenced earlier style to a more explicitly Japanese style of drawing figures and settings.

The monologue again plays a vital role providing necessary information. The framing of the bird’s-eye view moving slowly through live-action footage of smoke and zooming into the town where the boy lives provides an establishing shot similar to Fantascope, inviting the audience to enter this imaginary world. Again, the voice here is not the typical anime voice but something more realistic as found in Oshii Mamoru’s animated films.

Color is used to differentiate the characters. For example, the boy and his surroundings are usually depicted in grey. Yet, the girl and her surroundings are shown in gaudy colors, especially her appearance in his imagination. Also, color is used to express the character’s inner emotion. For instance, when the boy relates that his memory of the girl has slowly faded from his mind, she is depicted in an icy blue. Depictions of them together are usually done in off-white tones. Amano also experiments with distorted perspectives to depict dreamlike and surreal imagery. The distorted imagery resembles Salvador Dali’s style and the shifting images of real and surreal drawing quite successfully catch the viewer’s attention. This type of visualization of emotions is different from most anime. Even though there is no lack of surreal or dreamlike sequences in anime, Amano has interestingly designed and rendered his sequence with references to other artists.

Compared to Fantascope, there is more diverse camera work, including pans, tilts and dissolves instead of simple straight cutting. This element has added a more cinematic momentum and lively atmosphere yet it also draws Tori no uta back to a more mainstream construction of the images, like many other anime. Nonetheless, with its highly selective movement and relatively heavy usage of still images, the overall rhythm can still be considered slow, and the low monologue tone and soft conversation among the characters still contribute to its unusually quiet atmosphere.

The rendering of depth in Tori no uta is similar to Fantascope. We can easily distinguish the different layers which have been superimposed on each other in one image. The images do not look real. However, the exposure of the construction of depth between the layers is interesting as it invite us to explore the possibility of depth in a new cinematic manner.

The Dunwich Horror and Other Stories

There are three short stories in this title, an adaptation of H.P. Lovecraft’s short story with the same title. The first story, The Picture in the House starts with a traveler seeking shelter from the storm in an apparently abandoned wooden house. Later, the traveler meets the owner, an old white-bearded man. The old man shows an unusual fascination for an engraving in an old book depicting a butcher shop of the “cannibal Anziques.” The old man speaks in such an uncanny manner that it strongly suggests that he hungers for a similar sensation and the taste of human flesh. The traveler grows more and more uneasy with the old man. Before the old man could finish his talk, blood starts leaking from the ceiling onto the book they are looking at. The story ends abruptly when lightning strikes the house and everything falls into darkness.

As mentioned earlier, this work is the only three-dimensional work in the Ganime project that employs mixed materials. This work exhibits a more cinematic feel due to its use of extensive camera work such as a faster pace of pans, zooms and transitions. There is a greater variety of camera angles and changes between the subjective viewpoints of the traveller and the old man. The figures in The Picture in the House are designed to resemble human forms yet are less flexible. This aspect helps in developing the uncanny atmosphere that surrounds the characters. Mixed material and puppets/ models have never become mainstream in anime. Indeed, they are seldom categorized as “anime” but more often been labeled as “animation.”

In most scenes, changes are found in the characters’ facial expressions. Yet, these changes are rendered subtly and selectively, and sometimes are rather hard to distinguish in the dim surroundings. Although the gestures and facial expressions of these models could have been rendered smoothly with the stop-motion technique, it was clearly not desired. The creator only selectively animated certain elements such as the eyebrows and some other small details of his models. For instance, in the scene where the traveller first enters the house, his eyebrows are animated to rise slightly due to the dusty and ghostly atmosphere of the house. However, there are few distinctive facial expressions of the traveller in the following shots.

The next observable changes are when traveller raises his eyebrows higher while listening to the old man’s uncanny fascination for the butcher shop. The most dramatic change in the traveler’s facial expression is towards the end of the narrative when he tilts his head down and his eyebrows are intensely wrinkled, reflecting his uneasy feelings towards the old man while he watches blood leaking from the ceiling. It is true that the changes of the eyebrows are minute, but due to the focused attention on the slight movements of the eyebrows, the impact is strong.

Fig. 7 & 8 – The Picture of the House. Image courtesy of Spleen Films/Air Inc./Toei Animation Co., Ltd.

The restriction of facial expression is common in puppet animation. However, the director has further minimized the motion of his figures and, unlike the common pattern in Japanese puppet animation, he painted the clothes instead of dressing the figures with fabric. As a result of this process of reduction, the rigidness of the figures has effectively emphasized the alarming emotions of the character.

There is a mixture of reality and fantasy found in the overall construction of the models. The landscape details, including the muddy roads, rocks and sand, are all constructed realistically as are the wooden house and its interior. However, these realistic three-dimensional settings are placed against a flat-painted sky where the paintbrush strokes clearly expose the unreality of the set up. This generates an interesting contrast between the lifelike surroundings with their ambient atmosphere (such as the effect of the foggy weather, rain or the dusty room) and the artificiality of the brushwork. This contrast is enhanced by the difference in the human forms with their freely hand-drawn hair, beards and facial expressions; the unnatural whitishness of the characters’ skin color, as well as the texture of their skin suggested by the texture of the materials employed.

The design of the sound corresponds to the context in which it appears, for instance the sound effect of the rain, the footsteps, and the cracking sound of the door. The design of the diegetic and non-diegetic sound is similar to those in live-action films. However, the old man’s voice is the only voice in the later part of the film. Although the majority of scenes are of the old man’s conversation with the traveller, only the old man’s voice is presented to the audience, hinting at his survival. These mixed realistic and unrealistic presentations intrigue the audience leading them into this unconventional space.

Ganime and Selective Animation

Okada Toshio,9 anime producer, author, co-founder and former president of the production company Gainax, comments that Ganime is a movement that emphasizes a return to the individualism of the creator. He comments that although Tezuka Osamu started “limited animation” and the cel bank system to limit the cost of producing animated television series, complex narratives and unique styles of directing were used to balance the stillness of the imagery. The finished animations were exported to foreign countries, emphasizing profits gained by controlling the copyright.

Continuing this trend in the 1980s and 1990s, the construction of anime marketing through the categorization of works directed towards different age and interest groups is still intensifying today. Current anime creators are still constrained by marketing restrictions where the main rule is to make profit and auteurism is no longer an important element. Okada went on to contrast the career of Tomino Yoshiyuki, a talented anime director, who has been restricted to Mobile Suit Gundam series, with the internationally famous Oshii Mamoru who was able to direct The Amazing Lives of the Food Grifters (Tachiguishi Retsuden, 2006),10 even though it was not financially successful.11

Okada says the Ganime project can be seen as an extension of the new trend represented by Shinkai Makoto. In 2002, Shinkai’s Hoshi no koe (The Voices of a Distant Star) attracted attention by proving that it is possible to create anime by oneself, presenting an alternative to the existing anime production system in Japan. Shinkai adopted anime’s typical visual norms (particularly the drawing style), combining them with his atypical narrative setting to produce a love story. Even though his story involves a lot of fighting scenes, the emphasis is placed on the sensitive depiction of the inner emotions of the protagonist. This gives more depth and enjoyment through identification with the characters and poetic environment instead of the conventional fast pacing and flashing explosions typical of this genre. Besides its anime norms, the beauty of Shinkai’s Hoshi no koe is derived from careful observations and photographic-like details depicting the common sights and sounds of everyday life; for example, the signal of a railroad crossing, a signboard in front of a convenience store, advertisements found in the bus station and train, hand phones and the sound of cicadas.

Ganime’s expression takes simplification farther than Shinkai’s, as an exploration of the nature of the anime medium. Okada also thinks the mission of Ganime is to shorten the distance between creator and audience, similar to the function of the special comic market for doujinshi manga fanzines. For example, Ganime is a platform for established artists to experiment beyond their usual style, or simply display their interests without much interference. On the other hand, for those who have yet to establish their own name, Ganime can be an excellent medium to exhibit their talent and gain attention. They can try to achieve genuine expression and an auteurist viewpoint rather than focus on the perfectionism of animation professionals.12

Okada’s sharp observations recognize the distinctive quality and possibilities of Ganime as an excellent platform for the creators to explore and to experiment with a visual world that does not need to conform to any set of rules. Amano also expressed the same opinion in an interview, “…with Ga-Nime, I’m the only artist involved. Furthermore, by disregarding what is known as the standard, and drawing unrequired imageries, I was able to discover new things from this process.”13

Setting aside the marketing and commercial intention of Toei-Gentosha, the launching of Ganime project is extremely interesting. The Ganime project as a whole is trying to avoid many of the popular clichés in anime in order to explore new models of expression and visualization. That cyclic motion can be eye-catching if used creatively was shown in Fantascope and Tori no uta. The intense personal style such as the sumi-e style drawing in Fantascope and strong Japanese style imagery in Tori no uta has become a selling point. The integration of two-dimensional drawings and three-dimensional visual effects powerfully construct a quiet dreamlike atmosphere which is not based on the fluidity of the mediatory drawings found in full animation.

Similar treatment can also found in The Picture in the House despite its unusual mixed materials instead of drawn animation. The character figure designs for The Picture in the House generated a style that is significantly different from the usual anime and successfully created an interesting approach. Furthermore, the selective approach which usually animates facial expressions and poses other body parts in still gestures skilfully incorporates metaphors of the characters’ inner state. This technique generates a stronger impact by focusing the viewers attention when they are moved at the right moment, as in the above example of the old man’s eyes.

Ganime looks like a mixture of television anime series and feature-length animation, a combination of selective animation with the detail and higher quality of drawings found in the best theatrically released animation. However, Ganime targets an older, mature audience who want something beyond the stereotyped formulas of anime. This audience enjoys film, literature and music, with their complicated imagery and mature narratives.14

There has not been much discussion centered on Ganime in animation-related magazines.15 This lack of media coverage leads to the question of who is associated with this project. Looking at the essays in the 2006 book about Ganime – New Media Creation published by Gentosha, most contributors are from the fields of media, art criticism, literature, and popular culture. There is an unusual absence of film and animation-related specialists. A similar tendency can also be found in Ganime works. For instance, there are only a handful of anime people as most creators are from fields such as commercial directors, MTV directors, movie directors and artists. This unusual absence of anime regulars shifts attention to some other aspects of Ganime. Almost all Ganime titles have very high quality imagery whether they are drawings, engravings, photographs or CGI images. However, it is true to say that not all of them are presented in an interesting manner nor fully experimented upon in stretching the possibilities of the medium. Some of these great images were simply “edited together,” without deeply considering the purpose of employing stillness or motion, or their relation to the audio element. Therefore, these weaker examples do not break free from an amateurish look.

In the late sixties, Tezuka and Mushi Pro had employed comic gags and eroticism, and later employed a combination of avant-garde art and literature in order to attract an adult audience. Ganime in the twenty-first century tries to incorporate artists from different fields while also stressing elements of literature and music applied to high quality imagery with selective animation. Although the Ganime project has yet to achieve its goal, which is to break free from the current established anime pattern of industry and aesthetics, there is no doubt about its potential to attract creators who are interested in experimenting with the medium. In addition, the recent “call for entries” announcement on the Ganime project website16 opens up the possibility for new artists to create work with the financial backing of Toei Animation and with its powerful distribution network.17 This project is unique as an experimental venue financed by a major production company. It has the potential to extend the existing boundaries of animation, reaching a new audience through mainstream distribution channels.18 At the same time, it may also stimulate viewers to explore the new territories of animation. Ganime may not be the immediate answer to the current problem of the anime industry and it is also true that many Ganime creators are still influenced by the existing anime formats. Yet, these contemporary creators are once again trying to break free from the traditional pattern found in anime production, much like Tezuka’s attempt in the late 1960s. It remains to be seen whether they will finally be able to create an enduring creative future and spur new developments in anime.

The use of selective animation is not an uncommon visual expression in the contemporary anime product. Indeed, there is no lack of quality works that have employed this visual expression creatively. Anno Hideaki’s (the creator famous for his Neo Genesis Evangelion) popular anime series Kareshi kanojo no jijo (His and Her Circumstances, 1998) is one of the good examples. The recently well received anime series by Mitsuo Iso, Dennou coiru (Coil – A Circle of Children. 2007) is another such work. However, it is easy to observe that the creative usage of selective animation is not a common standard in anime.

The importance of the Ganime project is its intent to reject existing anime norms by encouraging individuality and creative use of selective animation. Even though it has proven difficult to fully realize this statement, the Ganime project has demonstrated some of the many possibilities of selective animation. Ganime creators have not only created new techniques, but have successfully experimented with existing techniques by reusing them in a creative ways. In short, Ganime project has stimulated a new angle to look at selective animation, as a powerful creative tool instead of a mere production shortcut.

Sheuo Hui Gan is a postdoc fellow of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) at Kyoto University. This paper was presented at “Animation Universe”, the 19th Society of Animation Studies Conference, Portland; June 29th – July 1st, 2007.

Notes

1 Selective Animation is a new term intended to replace the older expression “limited animation”. I present the idea of selective animation in the context of a spectrum of animation techniques in my dissertation “The Concept of Selective Animation: Dropping the ‘Limited’ in Limited Animation.” It is also discussed in my forthcoming article “The Concept of Selective Animation and Its Relation to Anime” in Animeeshon eiga no atarashii riron to rekishi (The New Theory and History in Animated Film).

2 The famous texts include works by Dazai Osamu (1909-1948), Hagiwara Sakutaro (1886-1942), Mori Ogai (1862-1922), Koizumi Yakumo (also known as Lafcadio Hearn, 1850-1904), Honoré de Balzac (1799-1850) and H.P Lovecraft (1890-1937). Noted contemporaries include manga by Hayashi Seiichi (1945) and Koga Shiichi (1936), photographs of Ueda Shoji (1913-2000), paintings of Yoh Shomei (1946∼), Amano Yoshitaka and so forth.

3 “Ganime: The Art of Slow Animation” is an article that appeared in the Arts Weekend’s column in the Daily Yomiuri, September 16, 2006.

4 I agree with Tsugata that there has been very little serious study of Mushi Pro and Tezuka’s animation, as most research focused on Tezuka’s manga with its wide range of themes, visual styles and influence on subsequent manga. Most current discussions of Tezuka’s animation tend to be introductory and placed as supplementary to his manga. There is another significant breakthrough that is often overlooked. Tezuka and Mushi Productions’ serious attitude to make animation was not limited to introducing animation for adults; they also inspired the use of more complex and meaningful subject matter in animation for children. Children’s expressions and unsophisticated language were used to communicate a deeper content. Therefore, their significant contribution to the popularization manga adaptations in to anime should be reconsidered in light of a key feature – the introduction of more serious issues and mature qualities into a stereotyped children’s genre.

5 I am borrowing the phrase “moving drawings” from Thomas Lamarre’s paper titled “From Animation to Anime: Drawing Movements and Moving Drawings” in Japan Forum 14(2), 2002. Lamarre used the phrase moving drawings to describe the technique commonly found in anime.

6 Recently there have been a few efforts to re-evaluate Tezuka’s achievements in animated films. Tsugata Nobuyuki’s new book, Anime sakka toshite no Tezuka Osamu – sono kiseki to honsitsu (Tezuka Osamu as Anime Auteur: His Record and Essence, NTT Shuppan, 2007), is the first such book, and is a useful reference work on these aspect of Tezuka Osamu.

7 A good example that utilized this attitude is demonstrated by Gankutsuou – The Count of Mont Cristo series of anime episodes produced by Gonzo, directed by Maeda Mahiro which originally ran from October 5, 2004 to March 29, 2005. There is an unusual sense of flatness in Gankutsuou’s visual effects, even though the characters and backgrounds are all rendered in three dimensions. Furthermore, Gankutsuou employs an unusual visual style that employs layers of texture patterns in the characters’ clothing, instead of standard coloring and shadowing.

8 For further interesting and detail discussion of flatness in anime and “animetism,” see “The Multiplanar Image” (120-143) by Thomas Lamarre in Mechademia: Emerging Worlds of Anime and Manga. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006.

9 Okada Toshio is considered a leading authority on otaku culture. He lectured on the topic at Tokyo University from 1992 to 1997. His books include Bokutachi no sennou shakai (Our Brainwashed Society) published in 1995 and Otaku-gaku nyuumon (The Introduction to Otakuology) published in 1996.

10 Despite what the official English title is, I think Biographies of the Distinguished Masters of Noodle Eating might be an attentive translation nearer to the meaning in the Japanese title. In this recent film, Oshii employs photography and CG to produce the effect of selective animation.

11 See Okada Toshio’s article in New Media Creation – Jisedai kurietaa no tame no shinmedea ganime (New Media Ganime for the Creator of the Next Generation), published by Gentosha, 2006: 10-17.

12 Okada 2006 p.17.

13 An on-line interview with Amano conducted at August 20, 2007 by Sawakama Keiichiro. Phofa.net (Phenomena for art): http://www.phofa.net/feature/2007/07/0707eng.html

14 Comparing a Ganime DVD priced 3129 yen to a thirty-minute DVD anime series, which usually ranges from ¥6300 to ¥8190 (occasionally discounted) per episode, the price of Ganime is actually much cheaper. Whether there is a sufficient audience for this new mode remains to be seen.

15 Nevertheless, the July 2007 issue of Animeeshon nooto – How to Make Animation Featuring Top Creators & Workflows featured a special interview with Amano Yoshitaka. They also used Amano’s female protagonist from Tori no uta for the front cover image.

16 Retrieved on June 18, 2007 from http://www.Ganime.jp/apply.html. It is obvious that Toei-Gentosha tries to explore new approaches and new market by recruiting of new talents with the Ganime project, with a minimum investment risk.

17 So far, the crucial financial aspect has yet to be clearly described by Toei-Gentosha.

18 On the Toei Animation official website, they advertise the Ganime project advertisement with eye-catching imagery that portrays styles different from other Toei’s productions: http://www.toei-anim.co.jp Retrieved on June 19, 2007.

References

Ga-nime Project. ed. (2006). New Media Creation – Jisedai kurietaa no tame no shinmedya gamine (New Media Ganime for the Creator of the Next Generation). Tokyo, Gentosha Media Consulting.

Gan, Sheuo Hui (2006). “Prefiguring the Future: Tezuka Osamu’s adult Animation and its Influence on Later Animation in Japan”; Proceedings of the Asia Culture Forum 2006 – A Preliminary Project, October 26-29, 2006, Cinema In/On Asia. Ed. Shin Dong Kim & Joel David. Korea, Asia Future Initiative, pp.189-200

Lamarre, Thomas (2002), ‘From animation to anime: drawing movements and moving drawings’, Japan Forum, Vol. 14 (2), pp. 329-367

Tsuki Mina. “Ga-nime: The Art of Slow Animation.” The Daily Yomiuri, September 16, 2006

Watanabe Tomohiro and Tanaka Kei (2007). “Animeeshon he no kaiki (The Return to Animation).” in Animeeshon nooto – How to make animation featuring top creators & workflows June, pp. 6-25

Wells, Paul (2002). Animation: Genre and Authorship. Wallflower Press: London & New York

© Sheuo Hui Gan

Edited by Nichola Dobson

![]() To download this article as PDF, click here.

To download this article as PDF, click here.