Reality is what we take to be true. What we take true is what we believe. What we believe is based upon our perceptions. What we perceive depends upon what we look for. What we look for depends upon what we think. What we think depends upon what we perceive. What we perceive determines what we believe. What we believe determines what we take to be true. What we take to be true is our reality. (Zukav, 1979, p. 328)

Introduction

Although animated documentary as a mode of representation has been around for about a century, academic studies began to consider various aspects of this increasingly popular medium almost a decade ago. Indeed, during the last few years, we can see an increase of scholarly interest on this subject. In spite of all these interests and attentions, however, “there is still a relative paucity in scholarly work on the form” (Honess Roe, 2009, p.2). This paucity of research in the domain of animated documentary has several reasons. A first reason might be, because animated documentaries are very diverse in forms and styles, and therefore it is difficult to analyze such diversity (Moore, 2010). It might also be rooted in that animated documentary, in its most radical form, tries to call ordinary ways of representing reality into question, and therefore it can be considered as an exceptional way of representing reality. Finally, and more importantly, the lack of a practical model for analyzing represented reality in animated documentary might be a further reason for scarcity of research in this area.

Ward (2008) calls for a model which considers the specificity of animated documentary, particularly its relation to reality as the most important factor in examining non-fiction texts. According to Ward, this model may be similar to mimesis/abstraction continuum developed by Furniss (1998) for analyzing moving imagery. Therefore, this research is an attempt to propose an analyzing model, hoping that such a model would help us expand our understanding of animated documentaries.

This research builds its model on a theory in semiotics. Semiotics deals with messages and tries to reveal the processes of meaning making. Animated documentary as a contemporary medium for communication conveys social messages, and it has, as its overall goal, some claims on reality representation. Thus, semiotics may help us reveal the unfamiliar processes of reality representation in those documentaries. Therefore, this study takes advantage of a theory in semiotics in order to establish its framework.

Theoretical background: A theory of semiotics

A central theme in contemporary semiotics is to uncover the process of meaning making and to answer the question of how reality is represented (Chandler, 2007). According to semioticians, we live in a world full of signs, and as Chandler puts it “we have no way of understanding anything except through signs and the codes into which they are organized” (p. 11). From a semiotic perspective everything can be perceived as a sign: words, images, sounds, gestures and even objects. On this basis, documentary filmmaking can be assumed as the practice of organizing codes, and therefore, documentary film can be understood as a system of organized codes or a system of signs. Hence, documentaries communicate or represent given realities through signs or codes. Therefore, it can be construed that animated documentary is also a system of signs (through which the audience is expected to conceive something as real). But, how can semiotics help us to uncover this system of signs? Buckland (2004, p. 7) comments that

Semiotics is premised on the hypothesis that all types of phenomena have a corresponding underlying system … The role of theory in semiotics is to make visible the underlying, non perceptible system by constructing a model of it … A model is an Independent object which stands in a certain correspondence with (not identical with, and not completely different from) the object of cognition and which, being a mediating link in cognition, can replace the object of cognition in certain relations and give the researcher a certain amount of information

Thus, we expect a theory of semiotics to help us reveal the underlying transparent sign system, employed by animated documentary, through developing a speculative model. In this study, a theory of semiotics will be adopted in order to propose a model for further analysis of animated documentaries.

Social semiotics

In traditional semiotics, a text is studied out of its context and cultural background (Stam, Burgoyne, & Flitterman-Lewis, 1992). Traditional semioticians hold that “just as people can only play a game together once they have mastered its rules, so people can only communicate, only understand one another, once they have mastered the rules of the game of language – and/or other semiotic modes” (van Leeuwen, 2005, p. 47). However, in social semiotics, meaning is negotiated during the process of reading. In other words, meaning-making is a complex interplay between the producer of the text and the social and cultural context in which the text is read. Van Leeuwen (2005, p. 4) succinctly explains

…just as dictionaries cannot predict the meaning which a word will have in a specific context, so other kinds of semiotic inventories cannot predict the meaning which a given facial expression – for example, a frown – or color – for example, red – or style of walking will have in a specific context.

Thus, social and cultural contexts are of particular importance in social semiotic studies and their significance should be emphasized in both theoretical and practical analyses of various texts. Hence, this paper borrows some concepts from social semiotics and multimodal analysis in order to propose a model for examining animated documentaries.

Multimodal analysis

Multimodality or multimodal analysis is a theory within the paradigms of social semiotics. It deals with communication in and across a range of semiotic modes such as verbal, visual, aural, etc. Therefore, it might be a suitable way of analysis for examining films, animations and other types of new media, whose multi-modal forms, structures and processes may not be well analyzed by older mono-modal analysis methods. Multimodality is originally rooted in Hallidayan social semiotics (Halliday, 1978), and is elaborated by Kress and van Leeuwen (2006) in the visual realm[1]. Since this research draws on the visual grammar of Kress and van Leeuwen, I shall explain some of the pivotal terms and concepts in Kress and van Leeuwen’s theory. Below, therefore, I briefly explain ‘mode’, ‘modality’, and ‘modality marker’ according to Kress and van Leeuwen’s visual grammar.

Mode

Although there is not an agreed-upon consensus on the definition of mode (Forceville, 2010), modes or modalities can be referred to as different resources for communicating messages. According to Jewitt, modalities or modes “are semiotic resources for making meaning that are employed in a culture – such as image, writing, gesture, gaze, speech, posture” (2009, p. 1). This culturally-bound nature of mode is also stressed by Kress who argues that mode “is a socially made and culturally given semiotic resource for making meaning” (2010, p. 79). Consider, for example, a simple conversation between two people; in a simple conversation, people use different resources/channels to make meaning. They communicate through verbal language; they use intonation as another resource for communication. There are also different facial expressions and body languages. All these resources/channels are different ‘modes’ by which people constantly make meaning.

Modality & modality marker

Modality is a term in semiotics that concerns with the status of a text, sign or genre in representing reality (Chandler, 2007, p. 65). It is originated from linguistics and is associated with the expression of possibility, certainty, obligation, necessity, etc. In language it appears in the use of modal auxiliaries (may, will, must, etc.), and related adjectives (possible, probable, certain, etc.) and adverbs (possibly, probably, certainly, etc.) (Martin & Ringham, 2006, p. 125). These modal auxiliaries, adjectives and adverbs are ‘modality markers’ in language. But, modality markers are not limited to linguistic terms, they can be found in other semiotic modes. Ward (2008) cites an example of a modality marker in documentary films; he argues that for the audience the authenticity of World War II (WWII) footages is bound up with ‘shaky black-and-white shots’, and therefore, he speculates that ‘shaky black-and-white shots’ are modality markers in that special context.

It should be noted that modality is a relative attribution of a message, and relates to social concepts and beliefs about reality. Kress and Van Leeuwen (2006, p. 155) assert that

[Modality] does not express absolute truths or falsehoods; it produces shared truths aligning readers or listeners with some statements and distancing them from others. It serves to create an imaginary ‘we’. It says, as it were, these are the things ‘we’ consider true, and these are the things ‘we’ distance ourselves from…

When we say, for example, that shaky black-and-white shots have high-modality in documentaries about WWII, it means that these kinds of footages are read more authentic and more reliable in that especial context and for the contemporary audience – the audience who are used to seeing WWII footages in that particular way. Thus, the degree of modality that we attribute to an especial modality marker is relative. Therefore, our judgments of modality depend on our conception of the world and are related to the norms, beliefs, and conventions of the social group in which the message is intended to be represented. In other words, “modality judgments involve comparisons of textual representations with models drawn from the everyday world and with models based on the genre” (Chandler, 2007, p. 65).

Methodology

As previously mentioned, this research is drawn from the social semiotic grammar of Kress & van Leeuwen. The study uses some concepts from social semiotics and multimodal analysis to construct a model for analyzing animated documentaries. To set up an initial framework, the larger research project will study four cases, the outcomes of which will be compared and then used in developing the model; in fact, the findings will be elicited from a cross-case study. However, this paper only discusses the first step and outlines methods used to build up the framework.

The data of the study

Since, the model proposed by this paper is based on comparison, a yardstick is needed as the basis for comparison. However, during the process of this research, it was conceived that it is not possible to use only one animated documentary as a yardstick. It is because animated documentaries are very diverse, not only in forms and styles, but in their philosophy toward representation of reality. They range from documentaries that try to represent an existing external reality, to postmodern documentaries which question the existence of external reality. Therefore, in order to increase the validity and practicality of the proposed model, it was decided to select the sample through purposeful data sampling technique. To this end, after stratifying animated documentaries into several groups, one animated documentary will be selected from each stratum which is the best typical example of that stratum. Following this method of sampling, it will also be possible to compare the outcomes on a well-structured basis which will lead into more useful findings.

Although there exist several typologies on animated documentary (see Hosseini-Shakib, 2009 and Patrick, 2004), Wells’ typology will be used as the basis for stratifying various animated documentaries. Wells divides animated documentaries into four categories: ‘Imitative’, ‘Subjective’, ‘Fantastic’ and ‘Postmodern’ (1997). The imitative mode comprises those animated documentaries that directly mimic the dominant generic conventions of live-action documentaries, e.g. expository narration. Subjective animated documentaries are those which try to reflect the personal subjective thoughts of an individual. More frequently, this mode uses animator’s artistic work in line with the real sound track of a real people. The sound track is usually an interview, recorded dialogues of ordinary people, or monologue of a person who describes his/her experience or situation. The fantastic mode takes advantage of unfamiliar, usually surreal, metaphors to tell the real in an unreal way and to redefine a new reality. The postmodern mode challenges ordinary ways of representing reality and questions the existence of the real itself. Postmodern animated documentaries suggest that documentary imagery is not an ‘authentic representation’ of the real-world, and therefore should not make any claims about ‘truth’ or ‘reality’.

As was previously mentioned, the larger project examines a typical example from each of the aforementioned modes to form yardsticks for the analysis of other animated documentaries. However, this will be accomplished in the next steps of the larger research project, and is out of the scope of this paper. As a result, this article does not introduce the typical example of each mode, and merely sticks to the elaboration of the method for establishing the framework.

The framework for data analysis

In order to analyze an animated documentary, through multimodal analysis, first we need to choose different modes that we intend to study. There are certain modes of communication in any kind of moving image. Some can easily be recognized, others may need more conscious attention. In this research four modes will be selected which are common in moving image: ‘visual’, ‘aural’, ‘motion’ and ‘Editing’.

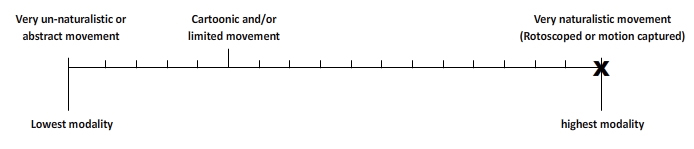

The next step will be to decide on modality markers. Modality markers, as already noted, are the cues that refer to the reality degree of a text within a certain genre as representations of some recognizable reality. “Modality cues within texts include both formal features of the medium (such as flatness or motion) and content features (such as plausibility or familiarity)” (Chandler, 2007, p. 66). Therefore, it is possible to choose modality markers from both formal and content features of a text. To illustrate the framework outline, an example will be discussed here. So, consider ‘character movement’ as an example of a modality marker within the mode of motion. Character movement can occur differently in animations. It can be very abstract, or might be very life-like – as in movements registered by rotoscopy or motion capture technique. After choosing modality markers then a continuum will be made per each modality marker for each animated documentary based on the model proposed by Kress and van Leeuwen (2006, p. 160), and then the continuum will be scaled – through interpretive case study of the four typical animated documentaries – by defining both ends of the continuum and the point of highest modality. However, the point of highest modality is not necessarily on either extremes of the continuum. Figure 1 demonstrates such a continuum. This continuum, for example, can demonstrate the modality scale of character movement, as a modality marker, in the subjective type[2].

In this figure the left end of the continuum is very un-naturalistic or abstract movement. The opposite end represents very naturalistic movement such as rotoscoped or motion captured movement. Cartoonic or limited movement is somewhere close to very unnatural movement. Then, where the highest modality lays on the continuum can be defined according to the examination of the subjective animated documentary. The point of highest modality is marked by an (X) on the continuum. Since the examined animated documentary is a typical example of subjective type, it can be used as a yardstick to analyze other animated documentaries in this category.

The modality scale of character movement for the imitative animated documentary, however, may look like figure 2. Here the point of highest modality is at the right end of the continuum. It suggests that the representation of reality in these two types differ from each other. In the subjective type, the highest modality was somewhere less than very naturalistic motion; however, in the imitative type the highest modality is the extreme naturalistic motion. These two diagram representations illustrate the process of designing and scaling the modality continua. Similar continua will be designed for other modality markers in any type of animated documentary. Consequently, we will have four continua for each modality marker.

Expected results and findings

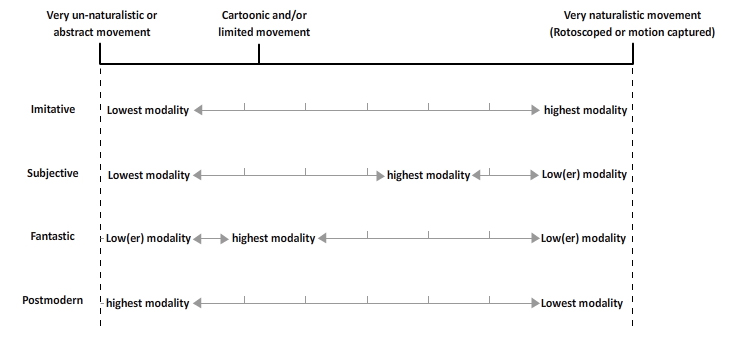

Doing a cross-case study and comparing the continua resulted from the study of each animated documentary will probably lead into more useful findings. It was discussed that the point of highest modality for a certain modality marker in one specific animated documentary will be different from that of the others. In the previous example, for instance, it can be seen that the point of highest modality in the subjective animated documentary was different from the one in the imitative animated documentary. It can be expected that this point of highest modality for a fantastic and a postmodern animated documentary may also differ from each other and from those of the aforementioned types. This can be explained by a useful term used by Kress and van Leeuwen (2006) which is ‘coding orientation’. “Coding orientations are sets of abstract principles which inform the way in which texts are coded by specific social groups, or within specific institutional contexts” (p. 165). In the case of animated documentary we can say that each type of animated documentary uses different representations to communicate reality. For instance, the imitative type, as Wells asserts, “directly echo[s] the dominant generic conventions of live-action documentary” (1997, p. 41), while the subjective type mainly links “the creative acts of the animator with apparent access to the subjective thoughts of their main characters (real people)” (Ward, 2005, p. 86). Therefore, we can say that these types have, to some extent, different coding orientations. It is then helpful to compare the modality scales of these different coding orientations – imitative coding orientations, subjective coding orientations, fantastic coding orientations and postmodern coding orientations. Figure 3 sketches such a comparison for character movement.

Fig. 3 – Example of modality values for character movement in four coding orientations (animated documentary modes)

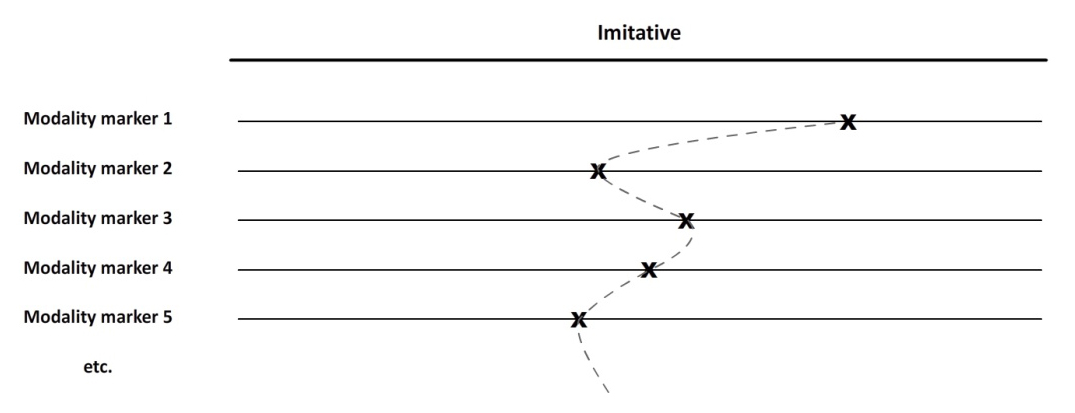

Diagrams like figure 3 can help us better judge on the specificity of each type of animated documentary and talk more easily about the representation of reality in such films. Additionally, there is a complementary diagram that will complete the development of a useful framework for examining animated documentaries. This diagram – also proposed by Kress and van Leeuwen (2006) – is called ‘modality configuration’. Although, the modality configuration proposed by this research is somehow different from the one proposed by Kress and van Leeuwen, both are based on a similar concept. Figure 4 shows such a diagram.

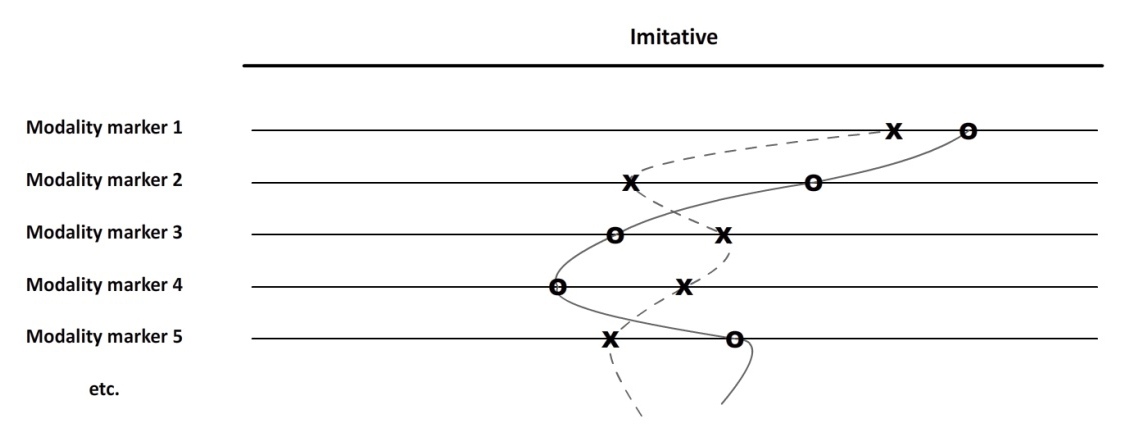

In this diagram, different modality markers, their scaled continuum and their relevant point of highest modality (X marks on the diagram) are listed. By connecting the points of highest modality, it is possible to make a pattern – as is visible in the diagram by dotted curves. Consider, for example, that we have constructed such a diagram for the typical imitative animated documentary. Then, we can use it as a yardstick and compare the pattern of this diagram with the patterns constructed for other animated documentaries from the imitative type or other types. Such modality configurations as Kress and van Leeuwen suggest “would describe what, in a specific genre or a specific work, is regarded as real, as adequate to reality” (2006, p. 172). Comparing the modality configuration pattern of an imitative animated documentary, for instance, with a typical one may result in a diagram like figure 5. Such a comparison will provide us with useful information about representation of reality in animated documentary.

Fig. 5 – Example for comparison of Modality configuration patterns for a randomly selected animated documentary and the typical example of imitative type

Diagrams such as figure 3 and figure 5, also raise some interesting questions: which modality markers play more significant roles in representing reality in each type? Which modes of communication are richer in representing reality in different types? Are the modality configuration patterns of films in the same type similar to each other? If yes, what social and cultural backgrounds lead to this similarity in representation? If not, is it possible to construct a typology according to these similarities in patterns? And so on.

Conclusion

This paper, as part of a larger project, attempts to provide a model for studying an unusual reality representation practice, known as animated documentary. For this, the article outlines a framework using a multimodal social semiotic approach. Considering that this paper is just the first step in setting up such a model, similar studies are necessary to adopt, calibrate and finalize this framework for practical applications of the model. Besides, internal and external validity of this model as well as its practicality should be tested by further studies. Examination of different animated documentaries with this model is also helpful for improving the framework. It is hoped that the final model would serve as a way to think about and to talk about animated documentary in general.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank my supervisor Dr. Fatemeh Hoseini-Shakib and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments which led to the current version of this article.

M. Javad Khajavi is an MA student in the Department of Animation & Cinema at Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran, researching animated documentary. This paper was presented at “The Rise of the Creative Economy”, the 23rd Annual Society for Animation Studies Conference, Athens, Greece, March 2011.

Notes

[1] Although Kress and Van Leeuwen have only drawn their grammar in the visual realm, their work is applicable to other modes. Adam de Beer’s work on movement in animation is an example (de Beer, 2009).

[2] It should be noted that all the figures in this article are only examples and are presented merely for illustration purposes and might differ from the real outcomes of the research.

References

Buckland, W. (2004). The Cognitive Semiotics of Film. Cambridge: CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS.

Chandler, D. (2007). SEMIOTICS THE BASICS. New York: Routledge.

de Beer, A. (2009). Kinesic constructions: An aesthetic analysis of movement and performance in 3D animation. Animation Studies , 4, 44-52.

Forceville, C. J. (2010). Book review: The Routledge Handbook of Multimodal Analysis. Journal of Pragmatics (42), 2604-2608.

Furniss, M. (1998). Art in Motion: Animation Aesthetics. London: John Libbey.

Hosseini-Shakib, F. (2009). The Hybrid Nature of Realism in the Aardman Studio’s Early Animated Shorts (PHD thesis). University of Brighton.

Jewitt, C. (Ed.). (2009). The Routledge Handbook of Multimodal Analysis. London: Routledge.

Kress, G. (2010). Multimodality: A social semiotic approach to contemporary communication. New York: Routledge.

Kress, G., & van Leeuwen, T. (2006). Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design (Second ed.). Abingdon: Routledge.

Martin, B., & Ringham, F. (2006). Key Terms in Semiotics. New York: Continuum.

Moore, S. (2010, 11 11). The Truth of Illusion – animated documentary and theory by Samantha Moore. Retrieved 11 22, 2010, from http://www.apengine.org/2010/11/the-truth-of-illusion-animated-documentary-and-theory-by-samantha-moore/

Patrick, E. (2004). Representing Reality: Structural/Conceptual Design in Non-Fiction Animation. Animac Magazine , 36-47.

Stam, R., Burgoyne, R., & Flitterman-Lewis, S. (1992). NEW VOCABULARIES IN FILM SEMIOTICS: Structuralism, Post-structuralism and beyond. New York: Routledge.

Van Leeuwen, T. (2005). Introducing Social Semiotics. New York: Routledge.

Ward, P. (2008). Animated realities: the animated film, documentary, realism. Reconstruction: Studies in contemporary culture .

Ward, P. (2005). DOCUMENTARY: THE MARGINS OF REALITY. London: Wallflower.

Wells, P. (1997). The Beautiful Village and the True Village: A Consideration of Animation and the Documentary Aesthetic. Profile no.53 of Art & Design magazine , 40-45.

Zukav, G. (1979). The Dancing Wu Li Masters: An Overview of the New Physics. New York: William Morrow and Company.

© Javad Khajavi

Edited by Nichola Dobson

![]() To download this article as PDF, click here.

To download this article as PDF, click here.