Introduction

This article is an examination of the use of animation in a participatory context in the United Kingdom during the period of the COVID-19 pandemic. It employs a case studies approach to record a collection of this largely unexplored area of the participatory animation arts, which here is understood as the joint effort that goes into the preparation and creation process of an animation project that involves different communities. The case studies are presented through a series of interviews and literature reviews. A reflective analysis aims to inspire and provide best-practice guidance for participatory arts. As is often customary in the creative arts, the article is written in the first person, as a narrative, a reflective journal, to illuminate the author’s thought process concerning participatory animation in online and physically distanced settings. It should be read having in mind the paradigm of social constructivism and the related view that knowledge is co-constructed in social settings, as well as the concept of the potentially unending and constantly improving spiral methodology of Action Research (see Vygotsky). Finally, the article claims that although animation bears many merits in its use as a participatory arts tool, unlike other means of participatory art-making such as mural painting, it does seem to require a healthy budget. Therefore, by highlighting the benefits and the difficulties of using animation as a participatory tool, I hope to inform practitioners of what to expect during such projects to help them plan better and to encourage funders to generously support such endeavors.

Context

As an artist who works with animation in a participatory manner for social change, I researched extensively the collaborative possibilities the medium offers. In my work, I apply participatory design methods to co-create animation, usually with marginalized people or people in conflict (see Christophini 2013; Christophini 2017a; Christophini 2017b; Christophini 2021). My work demonstrated that through this process of creative collaboration, communication among participants is often improved, while they also gain alternative means to express their point of view. My research champions that animation can accommodate a broad spectrum of creative expression to allow for multiple opportunities for collaboration in a setting that encourages the participants to lower their defenses and, in the case of people in conflict, to allow the process of re-humanizing those branded as enemies to begin. The positive experiences I gained from my previous research in participatory animation, prompted a naïve desire to apply my research experience to assist other participatory arts practitioners.

In a video conference held in the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic and the imposed lockdown by a Glasgow-based participatory arts network, I realized that most artists who worked in the participatory arts in the UK seemed to be out of work and concerned about the future of the social distancing policy or online-work mentality continued (see “Conferences and Talks”). During the same period, on the other side of the spectrum, although the film industry was in its majority detrimentally hit, animation stayed largely in production, even if it also had to adjust and slow its turnout pace (see Andreeva and Patten). Despite their drastically decreased budgets, many UK animators continued to do, roughly, what they were doing before; work in front of their computer screens, with online collaboration, from home (see Black; D’Alessandro; Sweney). Animation’s seeming resilience to adversity during the COVID-19 pandemic, coupled with my previous positive experiences in the collaborative animation field, led me to want to advertise animation’s potential for online collaborative opportunities with my frustrated peers in the participatory arts. I believed that animation would provide an answer to them, accommodating inhomogeneous groups of people who work from home and who may find themselves in different parts of the world.

In this article, I examine a variety of projects that apply animation in a participatory context. As I am currently based in Scotland, I have greater access to local projects, and therefore the cases I present here were created in the UK. Furthermore, I examine cases that took place during the pandemic, when most were forced to work remotely and from home. The ultimate aim of the essay is to create a record of the work produced during this difficult period in time but also to reflect on the choices and conditions of these practitioners to better plan for future projects that might take place under similar conditions.

Projects Created by Professional Animators: Flatten the Curve and Isolation Animation

The first two cases I examined were facilitated by professional animators with no participation by non-experts. Although such projects are expected to run more smoothly than projects created by non-professionals, it is still important to gather evidence of this assumption and to reflect on what and on why this is potentially the case, as well as to contrast and compare, at a later stage of this article, with projects created differently.

The first project I dealt with was Flatten the Curve, an animation professional collaborative film project organized by Kathrin Steinbacher and Emily Downe. The collaboration involved over 140 animation professionals from around the world who submitted around 90 short pieces of animation of up to 15 seconds, on their experiences of the pandemic (see Williams). The duo offered creative freedom in the choice of technique and required only that the clips depict something positive and follow the provided color scheme. The sent shorts were stand-alone clips, unified by the common general theme as well as the sound design (see Milligan). Steinbacher and Downe made the call online, created an online list where interested animators could enroll themselves, gathered the shorts over an online drive, and finally edited the material into three short films (see Williams). The benefits of expressing themselves in animation were for the creators, as for the audience, to be transported away from the physical boundaries of their homes, in which they were all confined during the lockdown (see Milligan).

Since the participants were professionals, they did not require any type of training, and each clip was created independently of the others and could in essence stand alone as well. The final clip provided exposure to the organizing duo and the other animators and allowed them an opportunity to express their creativity while emulating the collaborative manner in which animators worked in a period when human contact was prohibited. Collaboration seemed to run smoothly. The organizers did not have to deal with facilitating the learning of animation or software, care much about work division, and so forth. I would argue that this project ran straightforwardly, also because collaboration only took place in limited areas of production and not throughout the animation creation process. Dealing with professionals will naturally alleviate many technical issues. However, in my experience, dealing with non-profit projects may also bring egos to the fore, and with them dramas and difficulties.

Another project of similar online collaboration by animators was Isolation Animation, initiated by Roobot Productions. This project set out to lift the spirits during the lockdown and to bring animators virtually together (see Cooper). The parameters of the project were that each short new animation should start from the frame that the previous work ended with (see Cooper). The resulting mixed media animation, entitled Isolation, took place over 18 weeks and was produced using a variety of animation methods. It was a product of 31 different animation artists who answered the call for participation in this online creative community, and it depicted the artists’ experiences struggling with creativity during the lockdown (see Roobot Productions; Cooper). The main incentive of the project was not to tell interesting stories or to gain exposure for its creators, but to regain a sense of community, a creative support network in the animation world which the creators consider to be paramount for artistic work and which was lost during the times of social isolation (see Roobot Productions). This trampled my initial assumption that animators were not affected as much by the lockdown, as they were used to working online and from home. Indeed, many animators were based in shared workspaces, where they had the opportunity to socialize and have exchanges, something they greatly missed during the lockdown. Therefore, this community-building activity that collaborative animation offered was promptly taken by many and was valued.

In conclusion, although they required collaboration from professionals who in many cases had not met or worked together before, these two animation projects, as largely expected ran smoothly. All participants were professionals, they possessed the necessary skills, equipment and the all-important internet connection animation production requires. This eliminated the difficulties of teaching new skills and software and overseeing what to many are completely new group activities while working online. In essence, at least in terms of animating in front of a computer, the professional participants were practicing what they always had. The main difference for them was that they too had to deal with the general difficulties the environment of the pandemic brought about and that they worked with new collaborators and greater freedom than they normally would. Another significant difference between non-professional participants and professional ones was that the latter could arguably afford more easily the time on a project on which they might not have been paid, yet which offered many other benefits to their professional career such as exposure, or the participation in a bond-building activity with other animators and potential future collaborators or employers. To conclude, my takeaway from this project for future participatory animation projects is to involve in some manner a professional animator who can assist or advise on technique, equipment, and the management of such a project. Professional animators are used to working in an online setting and have great insight into the potential pitfalls and can provide time and energy-saving tips that can assist in the success of a project.

An Animation Workshop with the Bold Collective

An example of an online animation activity that concentrated more on introducing non-expert participants to the medium was an animation workshop I held for the Bold Collective in February 2021 (see “TBC Animation”). The workshop aimed at giving participants an idea of participatory animation creation and facilitated a group of approximately eight people. During a two-hour session, I taught the group the basics of how to animate and led them in creating their walk cycles in hand-drawn or collage animation. The participants used their computer screens as lightboxes to trace their walk cycles which were also a symbolic representation of them surviving the pandemic. I instructed the participants to consider their journey during the lockdown and reflect on a positive attribute they gained as a result of their adaptability during this period. The participants used their mobile phones to record their reflections and to upload all their work on an online drive, which I in turn could access to put all the individual clips together in one single short animation. The workshop was well-received by participants who seemed keen on learning how to animate and create a collaborative short. The downside of the experience was that the two-hour window I was offered to deliver the workshop was long enough to develop a very basic walk cycle and record some sentences that would form the basics of short animation. However, it was too short to foster any kind of meaningful interaction among participants. Furthermore, the screen participants used as a source of light to trace their drawings were in certain cases too small or inefficient, and it took a lot of effort to keep the drawings in place and aligned with the previous frame.

In retrospect, this workshop could have worked well if more time and equipment had been provided and if I, the facilitator, had better communication avenues with the participants, with whom I had no direct contact and no communication after the workshop. In the circumstance this workshop was delivered, it acted more as a super-fast trial session rather than a session that could bear actual results in a community building or skills developing sense. It did however intrigue the curiosity of several participants in the medium, as some contacted me in retrospect to enquire about animation lessons. Still, I would not advise holding such super short single-event sessions as the benefits of communal animation creation get lost and the concentration is mainly on a test run of the participants’ interest in the overall subject. Such a session can however act as a means to identify and plan for potential issues a longer-term project may present.

Leeds Animation Workshop for Bramley in Action

In September 2020 the Bramley Elderly in Action organization partnered up with the socially engaged women’s animation group Leeds Animation Workshop (LAW) to offer animation workshops as part of their Supported Wellbeing Project (SWIFT) (see “BEA”). LAW is a non-profit, cooperative, and women-led initiative based in Leeds. It was founded in 1976 and since then it has been active in creating a plethora of animations that dealt with several socio-political matters that were important to their community (see Christophini 2020). The LAW assisted elderly people over 60, who took part in the SWIFT program, in making an animated film about their experiences during the lockdown (see Christophini 2020). Before the lockdown, this group of elderly people used to meet regularly to socialize and exercise at their community center in the West of Leeds (see Blow). With the imposition of restrictions though, the elderly stopped their meetings. They started to shield themselves at home and, since many of them lived alone, they started feeling isolated and depressed (see Blow). Together with Bramazon and thanks to the support of Leeds Inspired, the LAW sent each elderly participant an animation kit and started working with them online to teach them the basics of animation over nine Zoom sessions (see Blow; Leeds Animation Workshop). The workshop was experienced by the facilitators and the participants as a project ‘full of steep learning curves all around’ with both parties having to quickly embrace change (see Wragg).

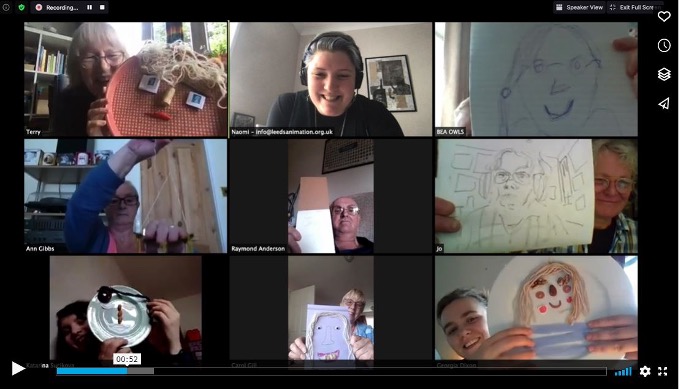

In response to the workshop, the LAW produced a short film (see Figure 1) that showcases short snippets from these online sessions the participants produced, as well as brief insights into their process (see Leeds Animation Workshop). It showcases the participants creating characters and props for their animation using everyday household materials such as pegs, paper, string, and kitchen utensils and bringing them to life using animation software on their mobile phones (see Leeds Animation Workshop). The short clearly shows those taking part enjoying themselves while learning and socializing.

I consider this workshop an example of a successful application of animation in an online participatory context since, contrary to my two-hour lightning-fast workshop, the participants had time to get to know the facilitators, experiment with the medium, and get their heads around some basic technology while socializing and bonding over the creation of animation. Although they produced a short film documenting their process at the end, as often is the case with participatory projects, the process was at the forefront here rather than the result (see Trienekens and Hillaert; Rutten, 1-8). This has probably alleviated the stress from the participants to produce a ‘polished’ outcome and allowed all parties to concentrate on the task at hand: the learning of a new art skill with others. Moreover, the project can be considered a success because the prolonged joint artistic creation acted as a motivating force to adopt novel approaches to learning and community building, especially if one takes into account the resistance to change that the elderly generations often showcase.

Apart from such animation workshops, the LAW is an organization that responds directly to the needs of their local community to produce films of an activist and informative nature that can be used to educate and form politics. Although they do not usually include the communities in the creation of animation of their films, they are participatory in the sense that their films involve communities in the research stages and consult with them throughout the creative process (see Leeds Animation Workshop). Following this example, participatory arts facilitators can empower communities by equipping them with some of the skills that involve their filmmaking process, even if those skills are not necessarily animation creation as such. An example of such skills could be training in research, publicity, or people’s and data management among others.

Nemo Arts Animation Work in Prisons

Another organization that is working with animation in a participatory context to bring about social change is Nemo Arts. The latter, previously known as Theatre Nemo, is a Glasgow-based community arts organization with a mission to support poor mental health sufferers, increase awareness around mental illnesses, and reduce social isolation through the arts (see Nemo Arts). Nemo Arts strives to create a safe and non-judgmental environment for its workshop attendees, where they can gain new experiences and competencies, increase their confidence and social skills, and feel part of a community of peers (see Nemo Arts). Among others, their projects involve learning songs on the guitar and the Ukulele, performance workshops, different visual art media, circus skills, as well as teaching Taiko drumming. Nemo Arts has used animation on several occasions and facilitated the participants of their workshops to create stop-motion animation pieces.

Three Families Inc. is one among many animation projects facilitated by Nemo Arts and was created by three families that had a father in HMP Addiewell prison (see Nemo Arts). The 2011 stop-motion project lasted over ten weeks and it was successful in building self-esteem and confidence among the family participants. It ‘allowed families to be families’ and provided them with something to look forward to, instead of just going through the usual emotions of a prison visit (Creative Scotland, 10-11). It provided an opportunity for the family to spend time together as equals. In turn, the imprisoned men felt they had a chance to a more positive identity as fathers (see Creative Scotland). Furthermore, the bonding between such families improved while working towards the achievement of a creative goal (see Nugent and Hutton). Nemo Arts was keen on using animation for the project due to the advantages that this medium presented, especially since animation is an art form most people wouldn’t do or have access to (see Nugent and Hutton, 3). This would make the medium new to most applicants. Therefore, working with animation would result in them acquiring a new skill (see Nugent and Hutton, 3). Furthermore, animation requires teamwork, which led to the development of interaction among the workshop participants (see Nugent and Hutton, 3). In fact, the participants mentioned that they gained a sense of achievement from the animation they created and considered the DVD they produced as the ultimate demonstration of their accomplishment (see Nugent and Hutton, 6). One further advantage of using animation according to Nemo Arts, is its potential to include the use of acting when recording the voice-overs for the different animation characters (see Nugent and Hutton, 6). In fact, Nemo Arts observed that during the recordings of projects, the confidence of the participants seemed to increase while they were ‘in character’ (Nugent and Hutton, 6). They also argued that ‘the use of characters provided an opportunity for the individuals to project something of themselves into an inanimate object, allowing them to be someone else’, and that examined from a ‘psychodynamic perspective which utilizes exploratory approaches such as play, this aspect of the animation process could assist with the expression of unarticulated emotions’ (Nugent and Hutton, 6).

Despite all these accolades for the use of animation, it is noteworthy, that at the end of the project, the participants mentioned that, although they enjoyed working with animation, in the future they would like to experiment working with a variety of art means each week, such as music, or painting (see Nugent and Hutton, 6). The partners and children also asked for an opportunity to continue aspects of the project at home (see Nugent and Hutton, 6). These suggestions for diversification of art skills and creation of home activities can easily be accommodated within a participatory animation project, by breaking down, for example, the different tasks that make up the animation into smaller sections. In this way, participants will be able to go through the different weeks dealing with the many distinct and varied aspects of animation creation. These can include among others, storytelling, acting, music, painting and drawing of the characters, scene design, editing, and more. Tasks can also be even further compartmentalized so that some people might deal with one task while others with another. Participants could also work on some aspects at home and then discuss and evaluate these during the meetings.

A drawback of using animation according to the participants was that they felt that the medium required patience, and they argued that young children could not fully engage with it properly (see Nugent and Hutton, 6). Animation is indeed a difficult and laborious process that does not yield immediate results. It might be though that this precise quality of the medium can act as a positive catalyst in the context of participatory work. This is because it can offer a group the opportunity to concentrate on the task at hand collectively and earnestly for a prolonged period. Working on a labor-intensive collaborative project over a relatively long time can also result in the development of qualities such as patience, persistence, teamwork, leadership, delegation, attentiveness, and the ability to focus and specialize. With the appropriate guidance, children engage with the medium to a greater extent if one shifts the emphasis of the activity to the process rather than on the result and makes them aware that animation requires hard work and effort and many failed attempts. Facilitators of such projects should consider evidence-based pedagogical approaches such as the scaffolding approach inspired by Vygotsky’s theory of proximal development, which reduces sessions into smaller distinct chunks (see Vygotskiĭ; Kurt). According to the scaffolding technique, the facilitator creates tasks appropriate for different age groups and experiences and plans on how to deal with potential frustrations (see Wood, Bruner and Ross). As the students become more knowledgeable and confident, support is gradually withdrawn (see McLeod). Still, it is important to also state that no one should insist on using a particular medium or method despite the wishes of the participants, or just for the sake of using the medium.

During the lockdown, Nemo Arts continued working, and they started a participatory animation workshop they had planned for the Fathers Network Scotland (FNS) before the lockdown (see McCue). This workshop is part of a Scottish government initiative to create training material for those who work with dads and families on understanding paternal mental health and the general experience of being a father (see Fathers Network Scotland). Nemo Arts has been working with participants from the FNS to facilitate the creation of short stop-motion animations on the subject. In an interview with Hugh McCue of Nemo Arts, I learned that working on this project online has been challenging (see McCue). They faced many difficulties such as getting the equipment and materials to the participants or training the participants on the technical aspects of the animation production virtually. Moreover, things like building a relationship with the participants, or dealing with simple technical difficulties such as using rulers, scissors, or the different software that enable both animation production and online communication became more strenuous when dealing with them in the distance and online (see McCue). Hugh mentioned that virtual communication created an additional barrier between him and the participants and that he did not feel like ‘he knew’ the participants. He even argued that he found working with animation in an online participatory manner more complex than other media (see McCue). As most participants would not have dealt with animation before, he had to explain everything from scratch and problems were harder to deal with in an online setting (see McCue). All these caused delays in the project which took much longer than the average ten weeks their projects usually last. He also explained that it was difficult to work on a collaborative project where participants could not physically share the process and the outcome of their production among themselves with the same ease (see McCue). The different sets, for example, were at different houses and, with physical distancing in place, this proved quite tricky for the production process. Participants and facilitators were nervous about the use of animation, and the facilitation of the project and its content, but eventually, people took ownership of the project and seemed to gain confidence working in this manner (see McCue). After nine months, Hugh explained that the project faced a phase of inertia, as the fathers were overwhelmed with home-schooling and other parenting obligations and could not dedicate to the project the amount of time it required to be completed (see McCue). The project is expected to create shorts that will bring insight into being a father following the different stages of fatherhood, from the relationship, pregnancy, the school system, and more. Unfortunately, Nemo Arts’ experience with online animation creation has been a rather negative one and both facilitators and participants found it difficult to cope with the time and technology demands of the medium. These practical difficulties are factors participatory arts practitioners interested in animation are encouraged to consider and plan for if they decide to go ahead with working with animation. One solution to dealing with some of the issues discussed above is the organization of regular group software classes with a reward system, perhaps a certificate of completion at the end, and a one-to-one tutorial system. The creation of the animation project could come at the end or simultaneously to these classes as a creative expression of the taught skills. Issues regarding the shared background could easily be solved by putting in place a courier system or switching to a different animation mode that is less physical and more digital.

Little Animation Studio

The last project I wish to examine is ‘Little Animation Studio’ (LAS), which was set up by Dr Katja Frimberger and Simon Bishopp with the assistance of Creative Scotland (see Bishopp). LAS employs innovative and accessible ways to support young people in expressing their needs through stories in animation (see Bishopp). The studio assists in the creation of all aspects of animation making, such as scriptwriting, voice recordings, characters, props, and sets. Just before the first COVID-19 lockdown in Scotland, Little Animation Studio collaborated with the care and education provider Harmeny Education Trust in Balerno, Scotland to assist children who experienced trauma in their early years to achieve their first fully animated film (see Hepburn). Before the lockdown, the pupils were shown videos of an animated ‘friendly robot’ who explained storytelling and the different roles involved in animation production (see Hepburn). The pupils then started engaging with the material and created a storyboard and a script. They also began drawing characters, props, and backgrounds (see Hepburn). Soon after the project’s initiation, the facilitators had to go into isolation, and communication was taking place online and with great time and effort sacrifices from the Harmeny Trust teachers and staff members, who were being guided by Frimberger and Bishopp to assist the pupils [who were residing in the school] in their creative journey (see Hepburn). LAS created several video and animation-based teaching and learning materials including interactive tasks accompanied by teacher’s notes, which accommodated the different needs of the pupils and led them and their teachers through the whole animation process online, which lasted over nine months (see Creative Scotland). With this guidance from the LAS, the pupils created drawings, plasticine models, and picture collages, and used gamepads, touch screens, and their voices and body movements to control their characters’ lives on-screen with motion capture technology (see Little Animation Studio). The animation that was produced, entitled The Mice and the Bakers, is a story of two cats, who are bakers, two mice, and two donkeys. Its central message is the idea that one good deed leads to another.

Reflecting on their experience, the facilitators expressed amazement at the ability of the children to rapidly adapt to new technology and even described instances where the participants led the session themselves (see Gallery Of Modern Art). They explained how the mutual honoring of time and effort was highlighted during the process and how the experience yielded something meaningful to all parties (see Gallery Of Modern Art). They also illustrated how working online had several advantages including greater flexibility in adjusting the pace of the workshop and the possibility of spreading the work over a larger timespan and into smaller chunks, rather than working with the time pressure and restrictions of fewer and set sessions (see Gallery Of Modern Art). The teachers were also excited about the project. However, when Frimberger and Bishopp self-isolated, much of the work was happening with the teachers’ mediation which ended up being a bigger task for them than anticipated. They also perceived the pupils to be less engaged, something they believed was because they were not dealing as much with the two new and exciting facilitators but with their teachers who they saw regularly and were very much used to (see Hepburn).

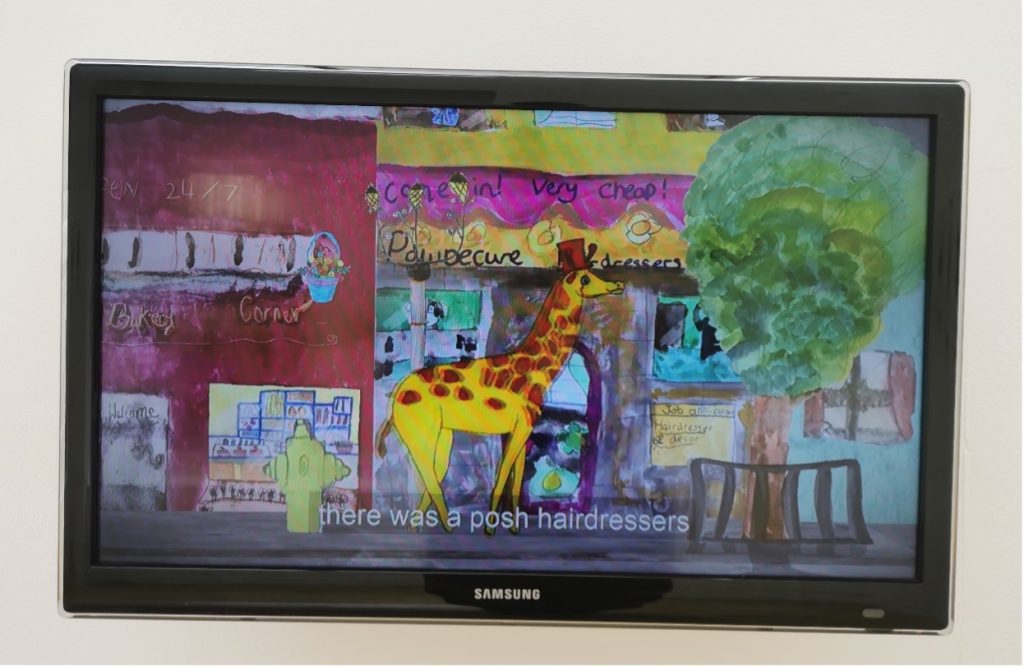

In general, the participatory work by the LAS was successful and all parties seemed proud of the final short. The participating pupils and staff had the opportunity to collaborate on a project that enhanced their soft skills, and knowledge of technology and the arts. Furthermore, they had the opportunity to produce a very high-quality short that familiarized them with the cutting-edge technology of motion capture and that was screened at the Gallery of Modern Art in Glasgow. The screening (shown here in Figure 2) at this important art museum and landmark for Glasgow was undoubtedly a source of pride for every child and guardian (see Gallery Of Modern Art). The fact that the pupils were all living together and had actual physical contact with their teachers during the project undoubtedly eased the facilitation of the project. Even though it seems that a great amount of work ended up on the shoulders of the teachers instead of the formal facilitators, the teachers also recognized the projects’ merits. They believed that the additional difficulties were brought about by the unforeseen atmosphere and situation caused by the pandemic rather than issues inherent to the project (see Hepburn).

Conclusion

This article set out to record some key cases of participatory animation work that took place during the difficult conditions of the COVID-19 isolation in the United Kingdom. It hopefully wishes to prove also useful in equipping individuals and organizations who intend to embark on animating in a similar participatory setting, with relevant knowledge on the subject and hopefully assist them in a successful outcome. During the COVID-19 pandemic, despite the many struggles determined by social isolation, participatory animation still took place with different levels of success all over the United Kingdom. Some of these endeavors are showcased in this article. Working with animation in a collaborative context during the conditions of the lockdown proved rather challenging for most of the cases I examined. The projects that seemed to work the best were those completed either by professional animators who already knew how to animate, who were already equipped with the appropriate technology, training, and support, and the shared space to work in physical proximity to each other while using the same sets and equipment. Involving a professional animator in such projects however can bring about other implications, such as a request for high fees that participatory arts projects can usually not afford. Most likely funding for such a project will not allow a professional animator to be paid anywhere near the fee they normally would if they were working at an esteemed animation company. Still, in my experience, many professionals are interested in partaking in such projects due to other, non-monetary benefits of community work. These benefits include the rewarding feeling of offering the joint good and positively impacting people’s lives, the meeting of interesting people one might not normally meet in one’s usual workplace while working on a matter that is important to them, or gaining a feeling of belonging and a chance to share, learn and influence.

Most difficulties the projects described faced do not seem uncurbable and instead act as lessons to be learned for future projects of a similar nature. Some possible future provisions one could make for projects with non-expert participants are, for example, to seek assistance and advice from professional animators in matters of technique and project management. Lightning-fast projects could be used to test the interests of participants and to predict and plan for possible difficulties that might arise in longer-term projects. Participants who do not know each other should ideally have enough time to get to know each other, the facilitators, and the project and should be able to easily exchange ideas and collaborate on the same artwork, something that seems easier on a digital platform and with digital means. Appropriate education on technique and project management among others should be provided and the multiple possibilities for work division in animation can be taken into advantage of to cater to the interests and strengths of each participant. These are some solutions among many. Unfortunately, though, even a simple animation, be it a traditionally drawn, a stop-motion or a digital animation project would still require some basic technology such as a computer, smartphone, or internet, which unfortunately, many people, even in first world countries such as the United Kingdom still cannot afford at home (see Jackson; Cossick). To counteract this issue, one solution can be the seeking of funding for community arts spaces within libraries or other public institutions such as universities, artists’ studios, or museums, which will be fully equipped and when not used can be put to the use of the community members in the same manner that computer spaces in public libraries are. Although gaining such funding is not the easiest of tasks, it is also not impossible to pertain. In Scotland, for example, there are numerous organizations related to the arts, among them Glasgow Connected Arts Network or the Scottish Contemporary Arts Network, that offer some limited funding to their members and even train them for successful application. Participatory arts facilitators should take advantage of such training and either start small and gradually aim for higher bids from affluent funders who will appreciate a successful funding record or use the skills they got from such training to directly apply for greater funds.

In conclusion, animation has the potential to offer worthwhile outcomes to the practice of participatory arts facilitators. Among others, it can digitally communicate messages on a time-based medium, via a combination of visual and acoustic elements, and provide a platform for prolonged collaboration and work division of people with differing skills, interests, and abilities with the goal of the creation of a unitary end-result, namely the animated film (see Christophini, 2017, 174-190). Animation can offer many opportunities for the cultivation of communities and the personal development of individual participants. It can render engagement with a great spectrum of the arts such as drawing, painting, sculpture, and model making, with scriptwriting and acting, as well as sound effects and score composition among others. It can also be a great opportunity for creative encounters with technology including cameras, 3D software, and AR technologies, and presents countless options for project management and the development of soft skills such as communication, teamwork, adaptability, persuasion, and perseverance. Animation provides the potential for a variety of different tasks, such as drawing, model making, acting, and scriptwriting among others, and for departmentalized and coordinated collaboration of participants working on these smaller distinct tasks. The at least partially false perception that animation is inaccessible to everyday people, along with the animation’s connection to childhood often makes the medium new and exciting. The lengthy time that animation usually needs to be completed allows for a sustained collaboration that may lead to the formation of stronger bonds, a protracted fostering of practiced skills, and greater investment in the project and the community. The completed outcome of an animated film, which can easily be disseminated across many media and platforms, seems to be a source of pride for many communities and sometimes a means to draw attention to relevant causes and campaigns. Still a great medium for community art, animation is probably better fitted to be offered in community centers, schools, and other mainly face-to-face settings, and like many participatory projects, with an emphasis on the creative process rather than on the aesthetics of the completed work (see Trienekens and Hillaert; Rutten).

This essay has presented some cases of participatory animation creation during the COVID-19-imposed lockdown in the UK. It did this to create a record of such work but also to provide a starting point to practitioners of the participatory arts who are interested in employing animation in their projects. By studying the successes and failures of these projects participatory arts practitioners can make an informed decision on when, why, and how to employ animation for their projects and funding organizations can better understand the needs of such projects and hopefully provide the financial assistance necessary.

Dr Myria Christophini is an award-winning Animator, Fine Artist and Researcher. She is currently working as an Assistant Professor at Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University.

Works Cited

Andreeva, Nellie, and Dominic Patten. “Animation Hasn’t Shut Down due to Coronavirus Crisis, but Slower – Deadline”. Deadline.com, 2020. https://deadline.com/2020/03/animation-tv-series-continue-coronavirus-challenges-1202890786

Bishopp, Simon. “Little Animation Studio – Showman Media”. Showmanmedia.co.uk. Accessed October 6, 2020. http://showmanmedia.co.uk/little-animation-studio

Black, Alex. “Why Animation Could Be the Answer to Advertisers’ Why Animation Could Be the Answer to Advertisers’ Covid-19 Content Production Problem”. thedrum.com, 2020. https://www.thedrum.com/opinion/2020/04/02/why-animation-could-be-the-answer-advertisers-covid-19-content-production-problem

Blow, John. “Elderly Leeds Friends Learn How to Make Animation – With ‘Bramazon’ Delivery”. Yorkshirepost.co.uk, 2021. https://www.yorkshirepost.co.uk/news/people/lockdown-fun-as-leeds-inspired-and-leeds-animation-help-bramley-elderly-action-to-become-animators-with-delivery-from-bramley-elderly-action-3186430

“BEA: Bramley Elderly in Action (@BramleyElderly).”It would be fair to say we’ve all had to adapt a lot in recent months”. Twitter, September 26, 2020, 9:55am. https://twitter.com/BramleyElderly/status/1306517119627124739

Christophini, Myria. Animating Peace: A Practice Investigation Engaged With Peace-Building In Cyprus. PhD thesis, The Glasgow School of Art, 2013.

Christophini, Myria. “Into The Choppy Waters of Peace: An Inquiry Into Peace- And Anti-Violence Animation”. Animation 12, no. 2 (2017): 174-190. doi:10.1177/1746847717708972.

Christophini, Myria. “Speaking Each Other’s Language: The Development of an Animation Prototype with the Intention to Toggle the Language Barrier Among Children of the Greek and the Turkish Cypriot Community”. Animation Practice, Process & Production 6, no. 1 (2017): 93-113. doi:10.1386/ap3.6.1.93_1.

Christophini, Myria. “Animation and Peace Studies: An Encounter for Societal Betterment”. Blog. Animationstudies 2.0, 2020. https://blog.animationstudies.org/?p=3619

Cooper, Lucy. “Isolation Animation Nominated at Indie Short Fest”. Blog. Animated Women UK, 2020. https://www.animatedwomenuk.com/isolation-animation-nominated-at-indie-short-fest/

Cossick, Samantha. “Living Without Internet? Join Nearly 33M Americans Who Aren’t as Well!”. Allconnect, 2019. https://www.allconnect.com/blog/33-million-americans-dont-use-internet

Creative Scotland. “Safeguarding Online Practices: Little Animation Studio”. Creativescotland.com, 2020. https://www.creativescotland.com/explore/read/stories/features/2020/safeguarding-little-animation

D’ Alessandro, Anthony. “How Feature Animated Productions Are Bucking The COVID-19 Climate – Deadline”. Deadline.com, 2020. https://deadline.com/2020/05/animated-movies-coronavirus-production-tom-and-jerry-spongebob-scoob-skydance-illumination-1202928961

Fathers Network Scotland. “Father’s Network Scotland / Lìonra nan Athraichean”. Accessed August 30, 2021, https://www.fathersnetwork.org.uk/

Gallery Of Modern Art (GoMA) Glasgow. “Little Animation Studio – The Mice and the Bakers”. Gallery Of Modern Art (Goma) Glasgow, 2020. https://galleryofmodernart.blog/little-animation-studio-the-mice-and-the-bakers/amp/

Harmeny Education Trust. “Roll out the Red Carpet…”. https://www.harmeny.org.uk/, 2021. https://www.harmeny.org.uk/learning-for-life-appeal/roll-out-the-red-carpet/

Hepburn, Nikki. “Interview by Author”, Online, Zoom, April 29, 2021.

Trienekens, Sandra, and Wouter Hillaert. Art in Transition: Manifesto in Participatory Practices. Ebook. Reprint, Brussel: f Demos vzw & CAL-XL, 2015.

Jackson, Mark. “ONS 2020 Study – 2.7 Million UK Adults have not Used the Internet – Ispreview UK”. Ispreview UK, 2020. https://www.ispreview.co.uk/index.php/2020/08/ons-2020-study-2-7-million-uk-adults-have-not-used-the-internet.html

Kurt, Serhat. “Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development and Scaffolding – Educational Technology”, Educational Technology, 2020. https://educationaltechnology.net/vygotskys-zone-of-proximal-development-and-scaffolding/

Leeds Animation Workshop, “Here Is the Story of a Series of 5 Workshops We Were Going to Do at Bramley Community Centre Last Spring.”, Facebook, March 21, 2020, https://www.facebook.com/Leeds-Animation-Workshop-118269331582472

Little Animation Studio. Little Animation Studio. Video, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ap21Frfdtyo

Little Animation Studio. “Little Animation Studio – Showman Media”. Showmanmedia.co.uk. Accessed October 6, 2020. http://showmanmedia.co.uk/little-animation-studio/

McLeod, Saul. “The Zone of Proximal Development and Scaffolding”. Simplypsychology.Org, 2019. https://www.simplypsychology.org/Zone-of-Proximal-Development.html.

McCue, Hugh. “Interview by Author”, Telephone. August 2020.

McCue, Hugh. “Interview by Author”, Telephone. April 22, 2021.

Mexi, Maria. “The Future of Work in the Post-Covid-19 Digital Era – Maria Mexi”. Social Europe, 2020. https://www.socialeurope.eu/the-future-of-work-in-the-post-covid-19-digital-era

Milligan, Mercedes. “Animators Around the World Come Together to ‘Flatten the Curve’ | Animation Magazine”. Animation Magazine, 2020. https://www.animationmagazine.net/shorts/animators-around-the-world-come-together-to-flatten-the-curve/

Nemo Arts. “Nemo Arts”. Nemo Arts. Accessed August 30, 2021. https://www.nemoarts.org.

Nemo Arts. “Three Families Inc. – Animation”. Nemo Arts. Accessed August 30, 2021. https://www.nemoarts.org/previous-prison-projects/three-families-inc-animation/

Nugent, Briege, and Linda Hutton. Evaluation of the Theatre Nemo Pilot at HMP Addiewell. Ebook. Reprint, Scotland: https://lemosandcrane.co.uk, 2011. https://lemosandcrane.co.uk/resources/Evaluation%20of%20the%20Theatre%20Nemo%20Pilot%20at%20HMP%20Addiewell%201.doc.

Roobot Productions. Isolation Animation Roundrobin 2020. Video, 2020. https://vimeo.com/425908849.

Rutten, Kris. “Participation, Art and Digital Culture”. Critical Arts 32, no. 3 (2018): 1-8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2018.1493055.

Steinbacher, Kathrin, and Emily Downe. Flatten The Curve. Video, 2020. https://vimeo.com/414349909.

Sweney, Mark. “How Coronavirus has Animated one Section of the Film Industry”, The Guardian, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2020/may/19/how-coronavirus-has-animated-one-section-of-the-film-industry.

Theatre Nemo. 3 Families Inc. Video, 2011. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ispdCKKoQ5c.

The Bold Collective, TBC Animation Talk Shop with Dr Myria Christophini Njenga – Glasgow Connected Arts Network (Glasgow Connected Arts Network, 2021). https://www.glasgowcan.org/event/tbc-animation-talk-shop-with-dr-myria-christophini-njenga.

The Harmeny Herald. “The Show Must Go On”, 2020. https://www.harmeny.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Harmeny-Herald-2020-pages-Reduced-PDF-.pdf.

They Call Us Maids: The Domestic Workers’ Story. DVD. Reprint, Leeds, U.K.: The Leeds Animation Workshop, 2021.

The Voice of Domestic Workers. Thevoiceofdomesticworkers.com, 2021. https://www.thevoiceofdomesticworkers.com/copy-of-events.

Whiting, Kate. “This Is How Coronavirus Has Changed The Film And TV Industry”. World Economic Forum, 2020. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/05/covid-19-coronavirus-tv-film-industry.

Williams, Megan. “Animators Unite to Put a Positive Spin on Lockdown”. Creative Review, 2020. https://www.creativereview.co.uk/lockdown-animations/

Wood, David, Jerome S. Bruner, and Gail Ross. “The Role of Tutoring in Problem Solving”. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 17, no. 2 (1976): 89–100. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1976.tb00381.x.

Wragg, Terry “Interview by Author”, Online, Zoom, October 16, 2020.

Vygotsky, Lev Semyonovich. Mind in Society. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1978.

Youth Theatre Arts Scotland, “Conferences and Talks | Talking Heads: Participatory Arts and Covid-19 – Glasgow Connected Arts” Network”, accessed August 30, 2021. https://www.ytas.org.uk/opportunity/talking-heads-participatory-arts-and-covid-19-glasgow-connected-arts-network/