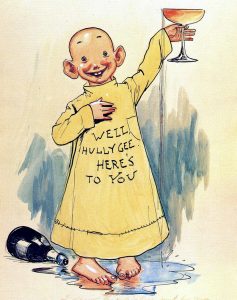

The centrality of both Richard Felton Outcault and Walt Disney to the development of cartooning in the United States is difficult to overstate. R. F. Outcault, as he was known professionally, is commonly credited with being “The Father of the American Sunday Comics” (Olson). On May 1, 1895, the cartoonist published the first installment of his new series, Hogan’s Alley. Set in the tenements of New York’s Lower East Side, the comic chronicled the antics of a group of raucous working-class children. The kids were led by a scrappy young boy whose given name was Mickey Dugan but who quickly became known by the nickname “The Yellow Kid” after the mustard-colored nightshirt that he commonly wore.

Hogan’s Alley was just one of many titles to appear in the new full-color Sunday comics supplement that Joseph Pulitzer launched in his newspaper the New York World, but it was by far the most successful. From the first installment, audiences delighted in the rowdy, and often mischievous, antics of The Yellow Kid and his pals. Before long, Hogan’s Alley “was read avidly by nearly a million readers” (Bolton 16). This tremendous popularity prompted William Randolph Hearst, who owned a rival newspaper, to lure the cartoonist away with a lucrative contract. The first installment of The Yellow Kid in Hearst’s New York Journal ran on October 18, 1896. That said, Pulitzer’s publication held the rights to the name “Hogan’s Alley,” so Outcault’s cartoons appeared under a new title: “McFadden’s Row of Flats.” Complicating matters further, the New York World continued to publish weekly installments of Hogan’s Alley, assigning the series to another staff cartoonist, George B. Luks. Over the next few years, comics starring The Yellow Kid appeared in both publications simultaneously. Outcault’s central character quickly grew so popular that even two newspapers couldn’t contain him. The Yellow Kid became “the first merchandized comic strip character, appearing on cracker tins, cigarette packs, ladies’ fans, buttons, and a host of other artifacts” (Harvey). Colin McEnroe, in fact, has identified more than 80 different commercial items to which Outcault’s protagonist lent his likeness, either through official licensing or unauthorized piracy. Given this situation, Christina Meyer identifies The Yellow Kid “as a precursor to the rise of transmedia franchise in the twentieth century” (53). By the time Outcault retired The Yellow Kid in early 1898 to pursue other professional endeavors—namely, his equally successful new comics character Buster Brown—“his work made him a fortune and turned him into a national celebrity” (Saguisag 1).

Two generations later, Walt Disney replicated this level of success in a different branch of American cartooning: animation. On December 21, 1937, the ambitious producer released his studio’s latest project, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Based on the classic fairy tale by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, the production broke new cinematic ground as the first feature-length animated movie ever made. Akin to Outcault’s Hogan’s Alley, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was an immediate commercial and critical success. The reviews were not simply overwhelmingly positive, they were exuberant. As Jonathan Frome has documented, the production was repeatedly called the best film of all time, (Frome 464–465). Moreover, Walt Disney was touted as nothing short of a genius (Frome 464–465). Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was as loved by audiences as it was lauded by critics. During its initial release, the movie netted more than $8 million, an impressive figure for any film at the time but especially for one that was animated rather than live-action (Hammond). Mirroring The Yellow Kid, Snow White gave rise to a bonanza of merchandise. Toys, games, sheet music, collectibles, clothing, home décor, dishes, and stationary connected to the movie-flooded stores. Within a year, industry insiders speculated that these products earned Walt Disney at least as much as its box office (Hammond). Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs remains a classic. The movie has been re-released theatrically eight times: in 1944, 1952, 1958, 1967, 1975, 1983, 1987, and 1993. In the same way that R. F. Outcault’s The Yellow Kid changed American newspaper comics, Walt Disney’s 1937 film changed the movie industry. The production’s commercial and critical success demonstrated that animated features were a compelling and even important mode of cinematic storytelling. In this way, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was a landmark film, both for the Disney studios and for American popular culture.

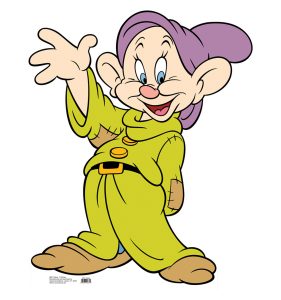

This essay brings together Walt Disney and R. F. Outcault, two influential figures in the history of American cartooning. More specifically, it identifies an overlooked connection between them—or, perhaps more accurately, recoups and restores one from its original historical era. In a detail that has not been explored in extant critical discussions about either Outcault’s groundbreaking comic or Disney’s landmark 1937 film, the character of Dopey possesses an array of striking similarities to The Yellow Kid [see Figure 1 and Figure 2]. From his bald head and large ears to his oversized nightshirt and goofy grin, Disney’s animated dwarf looks a great deal like Outcault’s newspaper protagonist.

Exploring the similarities between Dopey and The Yellow Kid adds a new source of influence on Disney’s groundbreaking animated film. For nearly a century, the cultural touchstone for Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs has been regarded as both a different country and a different century than the time and place in which it was created. From the version of the fairy tale on which the film was based to the setting in which the action occurs, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs is seen as taking place in Western Europe before the Industrial Revolution. How Dopey recalls and reflects The Yellow Kid complicates this viewpoint. Instead of being connected with an agrarian period in Europe, this character in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs has ties with the United States at the turn of the twentieth century during a time of tremendous immigration, rapid urbanization, and widespread industrialization. The suggestive echoes between Dopey and The Yellow Kid do more than change our perception of the overall film; they also change our perception of the specific role that the dwarf plays in the production. Outcault’s comic engaged with many pressing topics during the closing decade of the nineteenth century: economic inequality, urban crowding, and partisan politics. The way in which Dopey reflects and recalls The Yellow Kid invites us to re-examine this well-known figure and the scenes in which he appears in the context of Outcault’s work. Doing so imbues the 1937 fairy-tale film with new geo-political coordinates as well as socio-economic concerns. Ultimately, the suggestive echoes between the animated dwarf and the comics’ character add to ongoing discussions about the tension between imitation and innovation in the Disney oeuvre.

Grumpy, Doc, Happy, Sneezy, Bashful, Sleepy, and The Yellow Kid: Dopey as Mickey Dugan

While audiences delighted in many aspects of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs—the ground-breaking animation, the enjoyable music, the romantic story—, the dwarfs had special appeal. As J. B. Kaufman has written, “the dwarfs are the key to the picture: integral to the Grimms’ story, ideally suited to development in Disney’s medium” (Kaufman 51). These seven characters, with their distinct personalities, were the stars of the film for many viewers. At the very least, they were as important as Snow White herself. While viewers were fond of all seven members of the dwarfs, one individual stood out: Dopey. In the words of Kaufman once again, Dopey was “by any measure the dwarf most beloved by audiences when Snow White was released” (70). From his adorable personality to his comic appeal, the youngest dwarf was also a fan favorite.

Although Dopey was a unique member of the cast, he did not emerge from a creative or cultural vacuum. Akin to many other facets of the film, Walt Disney and his team were influenced by a variety of sources while creating him. The rubbery facial expressions of burlesque comedian Eddie Collins to the hitch-step of Stan Laurel in Bonnie Scotland (1935) (Pierce 127 – 128; Kaufman 73) are commonly cited in past and present criticism. Although these real-life individuals exerted an undeniable influence on Dopey, R. F. Outcault’s fictional protagonist The Yellow Kid can also be identified in Dopey. Indeed, J. B. Kaufman, in his book The Fairest One of All: The Making of Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs commented on this phenomenon, albeit very briefly. In a one-sentence remark in the main body of his discussion—and then again in a stand-alone caption on the same page—he commented how “Outcault’s pioneering comics character, the Yellow Kid, exerted an unmistakable influence on Dopey” (Kaufman 74). Beyond simply pointing out this detail, however, Kaufman does not explore it. Dopey is more than simply inspired by The Yellow Kid; he can be seen as a visual homage or aesthetic allusion to him. The beloved dwarf physically resembles the fin-de-siecle comics character, and he often functions in a manner similar to him as well. Exploring the areas of overlap between Dopey and The Yellow Kid more fully illuminates the influence that Outcault’s work had on the famous animated film. At the same time, these elements also alter our understanding of this well-known Disney character. One of the reasons why Dopey emerged as such a popular figure among the dwarfs was because he was the most childlike and thus, presumably, innocent. Unpacking how Dopey is indebted to The Yellow Kid challenges this longstanding belief. Dopey may be the youngest member of the dwarfs, but—akin to Outcault’s mischievous protagonist—he is far more impish than innocent.

* * *

Admittedly, none of the reviews of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs from when it was originally released in 1937 mention that Dopey resembled The Yellow Kid. While commentators remarked about many facets of the film—its compelling storyline, stunning animation, and memorable characters (including the dwarfs)—they did not call attention to any possible kinship between Disney’s dwarf and Outcault’s comics character. While it is possible that this element went unnoticed, another reason seems just as likely: the similarity did not need to be pointed out. For the original 1930s audience of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs—many of whom had grown up reading Outcault’s comic or, at the very least, being surrounded by the merchandise that arose from it—the likeness was obvious. Naming it was unnecessary.

Contemporary viewers of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, however, do not possess this same shared familiarity with Outcault’s The Yellow Kid. A connection that was once readily apparent has now become obscure. Just because the suggestive echoes between Dopey and The Yellow Kid are no longer widely recognized doesn’t mean they are no longer present, interesting, or even important. On the contrary, remembering and recouping the way in which Dopey recalls The Yellow Kid not only restores the original cultural context for this character, it also enriches our understanding of him, prompting us to see him in new and more complex ways.

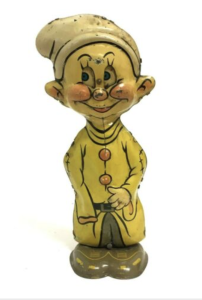

The physical likeness between Dopey and The Yellow Kid is striking. From his bald head and big ears to his large forehead and compressed facial features, Disney’s dwarf could easily be the brother of Outcault’s protagonist and perhaps even his twin. Moreover, in a further echo of Outcault’s character, Dopey’s mouth contains just one large front tooth [see Figure 3]. Adding to these qualities is the manner in which Dopey is dressed. His oversized tunic—with its long arms, baggy fit, and ankle length—is highly reminiscent of the nightshirt that Outcault’s character perpetually wears. Merchandise featuring Dopey enhanced these traits.

While the dwarf wore an olive-colored outfit in the 1937 movie, many of the toys, games, and figurines feature him in yellow [see Figure 4 and Figure 5]. When Dopey is attired in this way, his similarity to The Yellow Kid becomes even more apparent and, arguably unmistakable. Especially for Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs’ original audience, many of whom would have been familiar with The Yellow Kid from the comics section of their youth or the ongoing presence of Outcault’s character in popular culture, the kinship would have been obvious. In some ways, in fact, merchandise featuring Dopey provides a clear wink-and-a-nod to The Yellow Kid. If the dwarf’s bald head and big ears did not already remind viewers of Outcault’s protagonist, then dressing him in a yellow tunic would surely do so.

The overlap between Dopey and The Yellow Kid is not limited to visual points of reference; it also extends to the way that the characters operate, both individually and in group settings. Although Outcault’s character is routinely depicted in the company of a large crowd of kids, he is clearly their leader. In most panels, The Yellow Kid occupies both the foreground and center of the composition. In so doing, he functions as a type of host or even master of ceremonies for the events taking place. The Yellow Kid also offers commentary on some facets of these activities through the text written on his nightshirt. In such instances, Mickey Dugan does more than merely narrate the scene, he helps to orchestrate it.

Dopey functions in a similar way. Although Doc is the purported leader of the dwarfs, Dopey serves in this role in a variety of scenes. In a detail that is often overlooked but is certainly not inconsequential, he is the dwarf entrusted with managing the vault that holds the precious gems at the mine. One would think that Doc—who inspects and evaluates the gems—would be the one to perform this crucial job. But, it is Dopey who is entrusted with placing the bags of precious stones in the vault, locking it, and hanging the key back on the hook where it is stored. Managing the vault is not the only important task that Dopey performs for the group. When the dwarfs return home from the mine and discover that a stranger has entered their cottage, Dopey is the one sent upstairs to confront the “monster.” Admittedly, one might argue that he is the most gullible—and even expendable—figure, which is why he is the one sent. Nevertheless, Dopey is asked to perform this exceedingly vital task. After all, the fate of the entire group depends on him. Dopey likewise moves to the forefront of the dwarfs later that day, when they enjoy an evening of music. He is the member of the group who gets to dance with Snow White. Although Happy initially tries to be the young woman’s partner, he is too short for the combination to work. So, Dopey is the figure who climbs atop Sneezy’s shoulders. Arranged in this way, they form a partner of a proper height. The fact that Dopey forms the top half of this two-person pyramid is surprising. Once again, one might expect that Happy or Doc would be the figure to do so.

The Yellow Kid is more than simply the leader of the neighborhood kids, he is also their lead instigator. Whatever activity is taking place—from a raucous baseball game or makeshift dog show to a mock military drill or a fun afternoon at Coney Island—Mickey Dugan is participating, too. In many instances, in fact, The Yellow Kid seems to be the figure responsible for the event. In the panel “Hogan’s Alley Folk Sailing Boats in Central Park (June 28, 1896), for example, he is wearing a captain’s hat. Likewise, in “The Studio Party at McFadden’s Flats” (January 3, 1897), he is the artist who has painted a portrait of the scene’s main figure. Finally, and perhaps most vividly, in “Amateur Circus: The Smallest Show on Earth” (April 26, 1896), he occupies the role of the ringleader, both literally and figuratively. In these and other panels, The Yellow Kid is not simply participating in the mayhem, he is orchestrating it.

In a detail that has gone overlooked about Dopey, the youngest dwarf is also the most mischievous. When the group lets Snow White sleep in their bedroom, Doc repeatedly assures the young woman that they will all be “very comfortable” bunking downstairs. Whilst the rest of the dwarfs reiterate Doc’s assertion, Dopey does something far different and more devious: after spotting a big, soft pillow that is sitting on a wooden bench, he tiptoes away from the group towards it. Whilst his fellow dwarfs are busy reassuring Snow White, Dopey is busy trying to secure the only pillow for himself. This scene is not the only time that Dopey attempts to deceive other characters in the film. The next morning, when the dwarfs head off to work, Snow White bids them goodbye by kissing them on the top of their heads. Each dwarf is delighted by this loving gesture, and Dopey is so elated that he gets a clever idea. After receiving his kiss, the young dwarf races around to the back of the cottage, jumps through an open window, and comes out the front door again. His ruse works, and Snow White gives him another kiss. Revealing both the extent of Dopey’s affection for the young woman and his mischievousness, the young dwarf tries this trick again. Snow White rebuffs him this third time, but Dopey’s craftiness has already rewarded him with an extra kiss.

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs contains an array of memorable songs, from the early up-tempo number “Whistle While You Work” to the closing ballad “Some Day My Prince Will Come.” One of the most famous musical numbers in the film is also one that is performed by the dwarfs: “Heigh-Ho.” This tune, which the group sings as they journey both to and from the jewel mine, offers a snapshot of their worktime activities: “We dig dig dig dig dig dig dig from early morn till night/ We dig dig dig dig dig dig dig up everything in sight.” Although the dwarfs are singing about literal digging as they prospect for precious stones, contemporary viewers of Disney’s 1937 film benefit from engaging in figurative digging when it comes to Dopey. Recouping this character’s physical, behavioral, and narratological connections to Outcault’s The Yellow Kid constitutes another hidden gem in the film.

“Who’s the Fairest of Them All?”: Rethinking Questions of Integrity, Justice, and Equity in Snow White

The numerous ways in which Dopey recalls The Yellow Kid invites us to see the Disney dwarf as not merely a reflection of Outcault’s comics character, but a recreation of him. Viewing Dopey, not as another one of the “little men” who lives in the woods, but as a reprise of an immigrant youth who hails from the tenements of New York City, changes our perception of a variety of specific scenes as well as broad themes in the 1937 movie. Although Dopey may resemble The Yellow Kid from a physical, sartorial, and behavioral standpoint, the two characters occupy far different historical times and socio-political places. The closing decade of the nineteenth century, when R. F. Outcault’s comics series was created and published, was one of the most dynamic periods in American history.[1] Immigration, industrialization, and urbanization were expanding at unprecedented rates (Brands 100–106). Additionally, the nation’s social, technological, and cultural life was experiencing massive change. Inventions such as the phonograph, the new electric streetcar, and the rise of motion pictures would forever change the fabric of American life (Brands 40-50). Outcault’s comics featuring The Yellow Kid weren’t simply published in the midst of these events, they engaged with them directly (Blackbeard 35–80). From openly confronting issues like poverty, urban crowding, and political corruption to tackling subjects like nativism, classism, and xenophobia, Outcault’s work featuring The Yellow Kid existed at the forefront of what would come to be known as “the funny pages” in U.S. newspapers, but they were also political cartoons in many ways. The panel “Hogan’s Alley Preparing for the Convention” provides an excellent case in point. First published on May 17, 1896, roughly a month before the Republican convention in St. Louis, the image satirized the event. The Yellow Kid is located in the center and foreground of the picture, surrounded by dozens of other children, all of whom are enthusiastically marching in the same direction. A sign in the background reads “To St. Loous,” the site of the convention. While some of the children are playing musical instruments and others are waving American flags, many of the kids are holding four-sided wooden signs. The political commentary contained in these remarks is not even thinly veiled. One sign affixed to a rolling cart reads “Dis is de Republican movable platform/De planks is all loose and reversible, and can be moved to suit de winner” (sic). Meanwhile, another placard that is just behind it relays “Notice advertising space on dese banners kin be had in exchange fer votes.” The message on one of the faces of a four-sided sign near the back of the group is just as pointed. It announces: “Free silver or anything else that’s free./Free lunch is our favorite” (sic). As even this brief analysis demonstrates, much of the humor in Outcault’s work arose from socio-cultural commentary.

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs seems far afield from both this environment and these concerns. The film was made more than 40 years after the infamous Gilded Age in which Outcault lived and worked. Additionally, the 1937 movie contains far different national, geographic, and societal coordinates. Whereas Outcault’s comics featuring The Yellow Kid were urban, working class, and focused on socio-political problems in the United States, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs takes place in a setting that is European, pastoral, and idyllic in many ways. The opening scene of the movie depicts a majestic royal castle. Meanwhile, the dwarfs live in a rustic cottage in the woods. Finally, the forest is filled with adorable animals who not only befriend Snow White but help her cook and clean. Given these details, Disney’s fairy-tale film is seen as offering an escape from, rather than an engagement with, current events. From its bucolic setting to its anthropomorphic animals, the movie traffics in fantasy, not realism. This viewpoint is augmented by the fact that Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was created and released during a tumultuous era in the United States: the Great Depression. Whilst the nation was experiencing record levels of unemployment, widescale foreclosure of homes, and an unprecedented environmental crisis with the Dust Bowl in the Midwest, the characters in Disney’s film were mining diamonds, living in a comfortable cottage, and cavorting with cute animals in a lush forest.

Seeing Dopey as a conduit for, or a reprisal of, The Yellow Kid changes our perception of the film’s setting along with several of its key scenes. In marked contrast to Outcault’s comics, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs is not regarded as a political film that engages in a socio-cultural commentary. Indeed, although Snow White’s stepmother is indisputably evil, her failings have commonly been attributed to the fact that she is a vain and insecure woman, rather than a corrupt and tyrannical ruler (Gilbert and Gubar 36–46). Phrased differently, the Queen’s despicable actions are seen in the context of her gender, rather than through her abuse of power. Seeing how Dopey channels The Yellow Kid invites us to reconsider this detail. While Snow White’s stepmother is certainly a shallow and petty woman, she is also an unprincipled and incompetent ruler. Although the Queen is referring to external beauty when she asks the magic mirror “who is the fairest of them all,” this comment can also be viewed in a far different context: as a barometer of how she treats her subjects. The evil Queen, of course, has no regard for justice, ethics, or morality. Snow White does not merely pose a threat to the Queen when it comes to physical appearance, but also, of course, when it comes to the throne. The young woman would be a far better ruler of the kingdom: she is kind, caring, and empathetic. Unlike her horrid stepmother, she would treat her subjects compassionately and—above all—fairly. Questions of justice, fairness, and leadership were major national concerns during the 1930s. The Great Depression brought issues of economic equity, along with the fitness, competence, and integrity of those running the government, to the forefront. When the stock market crashed in 1929, banks failed around the country, and millions saw their life savings vanish overnight, many Americans questioned the fairness of Wall Street. How could so few control the economic fates of so many? Where was the integrity of the nation’s banking system if an individual’s funds were not secure in their accounts? Finally, and perhaps most concerning of all, if the entire financial system of the United States could be so easily manipulated and thoroughly destroyed, where was the sense of fair play?

When Franklin Delano Roosevelt was elected in 1932, he sought to address these issues. His New Deal programs were funded by tax measures that, in a phrase that has now become commonplace, made sure that the wealthy paid “their fair share” (Thorndike). Economic opportunity and class mobility were core tenets of U.S. life. Fixed economic systems where the wealthy grew wealthier while average people had little hope of improving their lives prompted many individuals to immigrate to the United States in the first place. Especially amidst these difficult economic times, it was vitally important that average citizens were given a fair chance to support themselves.[2] FDR’s programs like the Works Progress Administration and Civilian Conservation Corps aimed to do just that. Of course, having a job meant little if the wages one earned could not be safeguarded. As a result, Roosevelt also passed an array of banking reforms and fiscal regulations. From the Federal Reserve System and the Securities Act to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation and the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, these measures oversaw the nation’s financial institutions to make sure that they operated appropriately, consistently, and—echoing a key word in the evil Queen’s query to the magic mirror—fairly.[3]

When R. F. Outcault’s comics were not engaging with political issues, they were raising questions about socio-economic class. The cartoonist established in his debut panel that his comics series would focus on the hardscrabble life of working-class immigrants. Called “At the Circus in Hogan’s Alley,” the drawing depicts a large group of children in an empty lot behind a tenement. As the title of the scene suggests, the youngsters have created their own neighborhood circus using items that they have on hand. While it is possible that the kids from Hogan’s Alley had so much fun attending the professional circus that they decided to recreate one in the empty lot, it seems more likely that they are too poor to purchase a ticket to the actual event and so are making one of their own. Details throughout the panel seem to affirm this belief. The children in Outcault’s drawing wear clothing that is ragged, torn, and ill-fitting. Additionally, few of them are wearing shoes, presumably because they don’t possess any. Finally, the empty lot where they stage their theatrics is strewn with garbage: dented tin cans, old boots, and crumbled papers litter the ground. The Yellow Kid himself is not immune from these conditions. His nightshirt—which is pale blue in this early drawing—is marred with dirty handprints. The area around his neck is also filthy, seemingly stained with food. Moreover, the youngster’s head is shaved, though likely not as an intentional hairstyle. Rather, as readers in the 1890s would immediately recognize, The Yellow’s Kid’s head is bald because doing so was the fastest, easiest, and cheapest way to treat head lice (Harvey). Given these details, Outcault’s work has commonly been placed in dialogue with the work of photojournalist Jacob Riis. In his groundbreaking book, How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York (1890), Riis exposed the appalling living conditions on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. From images of streets filled with fetid garbage, putrid sewage, and rotting dead animals to those depicting squalid rooms that had no natural light, fresh air, or running water, Riis’s photographs shocked middle- and upper-class Americans, sparking reform. R. F. Outcault’s comics featuring The Yellow Kid are often seen as being in dialogue with Riis’s documentary photography. In panels like “At the Circus in Hogan’s Alley,” Outcault presents a far different portrait of American life, and especially of nineteenth-century childhood. Instead of cherubic boys and girls enjoying an afternoon at a lovely professional circus, he presents a group of filthy kids staging a makeshift rendition in a trash-filled lot. That said, Outcault’s panels were not mere exposés of economic inequality and indictments of urban squalor. The cartoonist depicted the hardships faced by the working classes, but—in contrast to the photographs by Jacob Riis—he also presented their joy. Even though the kids in “At the Circus in Hogan’s Alley” are unable to afford a ticket to the professional circus and are improvising their own in a vacant lot, everyone seems to be enjoying themselves. Many of the performers have smiles on their faces. Likewise, the majority of kids watching the amateur circus—from the wooden fence on the left side of the drawing, the plank bench on the right, or the second-story window in the background of the composition—are grinning gleefully. Even Mickey Dugan, with his bare feet and filthy blue nightshirt, is laughing joyously. As a result, Outcault calls attention at least as much to the fun that the youngsters are having as to the hardships that they face.

Seeing Dopey in the context of The Yellow Kid brings socio-economic issues to the forefront of the film. Akin to Mickey Dugan and his friends, the seven dwarfs are working-class figures. First and perhaps most obviously, they engage in arduous physical labor as miners. While they excavate precious gems, they don’t appear to own the operation. Rather than taking the valuable diamonds home at the end of the day, they lock them in a vault on site. Additionally, the dwarfs live comfortably, but not lavishly in the woods. The seven characters all share one upstairs bedroom. Their beds are packed in so tightly, in fact, that Snow White is able to lay comfortably across them. Finally, and in a detail that brings them in closer connection with Outcault’s Yellow Kid, when Snow White first enters their cottage, it is very dirty. Cobwebs wallpaper each room, dirty dishes are stacked in the sink, and a thick layer of dust covers every surface. In this respect, the interior of the dwarfs’ cottage could easily be the interior of one of the tenements on the Lower East Side—or in Jacob Riis’s photographs.

Akin to The Yellow Kid and his companions, the lives of the dwarfs might be regarded as pitiable. The characters spend their days performing arduous physical labor, and then they return home to a dirty cottage. However, in another link between Disney’s Depression-era film and Outcault’s fin-de-siecle comics, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs does not present the dwarfs as miserable or even dissatisfied. On the contrary, when viewers first meet the characters, they are working contentedly—and even happily—in the mine. None of them seem physically taxed or psychologically drained. Even Grumpy engages in the “dig, dig, dig” without complaint. Additionally, after finishing their labor for the day, the group marches home, joyously singing the upbeat song “Heigh-Ho!” Their life seems not merely satisfying, but enjoyable. The dwarfs might be working class, but—akin to The Yellow Kid and his friends—their socio-economic status is not synonymous with despair. This message is not limited to one scene. A variety of other episodes in the 1937 film affirm that the dwarf’s modest life is not a cause for lament, but a source of satisfaction and even joy. The scene where the group insists that Snow White sleeps in their bedroom is an excellent example. Happy assures the young woman that they will be “very comfortable” bunking downstairs. This vow is anything but polite hyperbole. After a comedic scramble over a pillow, the dwarfs all settle in and fall soundly asleep, curled up on various pieces of furniture. Such images—of gray-haired men sleeping in cabinets, drawers, the washtub, and even the iron kettle over the fire—could easily be viewed as lamentable. Indeed, some of the most shocking and powerful photographs in Jacob Riis’s How the Other Half Lives depicted both children and adults sleeping in stairwells, on wooden pallets and chairs, and over street grates. This scene in Snow White, however, does not function in this way. Forming yet another area of overlap with Outcault’s panels featuring The Yellow Kid, the dwarf’s decision to sleep in these alternative areas is not only acceptable but agreeable. It is not cause for pity or even alarm. Although the dwarfs have made their beds in unconventional places around the cottage, they are—as the group had repeatedly assured Snow White—very comfortable. This message, of course, has obvious implications for the film’s original Depression-era audience, many of whom were learning how to make do—and even find joy—in drastically reduced material circumstances.

* * *

Time magazine, in their review of Disney’s new full-length animated feature, declared: “Snow White is as exciting as a Western, as funny as a haywire comedy. It combines the classic idiom of folklore drama with rollicking comic-strip humor” (“Mouse and Man” 20). While the magazine was referring to the movie’s use of slapstick, its comment about Snow White borrowing from newspaper comics was apt. Together with incorporating the physical comedy that typified many strips, Disney’s groundbreaking feature also incorporated elements from a groundbreaking comics series. The name of Disney’s dwarf notwithstanding, Dopey may not be as “dopey” as he has long been regarded. Far from a simpleton, this beloved character might be a complex amalgamation of Outcault’s lively protagonist and equally compelling comics.

Innovation and/as Imitation: Dopey and the Issue of Originality in Disney

From its origins, the success of Walt Disney and the entertainment empire that he created has been attributed to the originality of the productions. The studio’s animated films have been beloved by audiences and lauded by critics because they are so innovative. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, for instance, featured new paint pigments that allowed the animation to look more realistic, devised a better method for syncing sound, and filmed many scenes using a new multiplane camera that gave the drawings more depth (Frome 463–465). These elements impressed viewers and reviewers alike. In fact, Walt Disney received an honorary Academy Award for Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs the following year. The statue celebrated the production’s “significant screen innovation” and was, quite appropriately, innovative itself: it was comprised of one regular-sized Oscar with seven smaller ones trailing it.[4] Subsequent Disney productions have likewise been known for breaking new aesthetic, technical, and narratological ground. Lady and the Tramp (1955), for instance, introduced widescreen animation. Meanwhile, One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961) pioneered the use of xerography. Moreover, The Rescuers Down Under (1990) marked the debut of computer-generated drawing.[5] As even these few examples reveal, Disney has been at the forefront of the industry for nearly a century (Rindskoff).

The way in which Dopey recalls and reflects Outcault’s The Yellow Kid complicates longstanding views about the narratological originality and character innovation of Snow and the Seven Dwarfs. Although Disney used the Grimm Brothers version of Snow White as the basis for the film, the studio made the story their own. In keeping with the longstanding tradition of fairy tale narrators adding their unique details, Disney did the same. From omitting the two additional times that the evil witch kills Snow White to changing both the length of time that Snow White slumbers and the manner in which she is awakened, the 1937 film incorporated specific edits that made the story distinct. That said, as critics like J. B. Kaufman, John Canemaker, and Bruno Givreau have discussed, one of the biggest and most important changes that Disney made was giving the dwarfs individual names with equally individual personalities. Doing so not only allowed Disney to add content to an otherwise brief plot but also to add something inventive to the production. As Kaufman notes, “In a sense, the dwarfs are the key to the picture: integral to the Grimms’ story, ideally suited to development in Disney’s medium” (51). Both reviewers in 1937 remarked and critics today continue to affirm that the seven dwarfs are one of the most memorable elements of the film. Doc, Grouchy, Sneezey, Sleepy, Bashful, Happy and, of course, Dopey, are known the world over. Just as importantly, they are known as products of the Disney imagination.

How Dopey physically, behaviorally, and thematically evokes The Yellow Kid challenges longstanding claims about this character’s originality. Instead of being seen as a wholly distinctive creation, the figure can perhaps more accurately be viewed as one who is a reprise, an allusion, or even a homage. From Dopey’s clothing and visage to his conduct and the role that he plays in the film, he recalls and reflects The Yellow Kid. These areas of overlap add to ongoing discussions about the tension between innovation and imitation in the Disney oeuvre. This phenomenon predates the release of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs; it can be traced back to the studio’s earliest short films. In 1928, the Disney studio released “Steamboat Willie.” In what has become an oft-repeated history, the cartoon not only established the company’s name in the animation industry but also established the character who would become its most recognizable icon: Mickey Mouse. Although Mickey is inextricably linked with Walt Disney, the mouse is not as unique a creation as his subsequent notoriety might suggest. As critics like Neal Gabler and Whitney Matheson have discussed, Mickey was based on Disney’s earlier character, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit. In the words of Gabler, the rodent is “essentially Oswald with shorter ears” (113). Walt Disney, however, did not own the creative rights to the successful rabbit; his distributor, Universal Pictures, did. At a meeting in March 1928, Charles Mintz at Universal Pictures insisted that the animation studio take a pay cut for producing the very lucrative Oswald shorts, and Walt refused, severing their professional relationship (Finch 22; Susanin 175). Disney released “Steamboat Willie,” starring Mickey Mouse, on November 18, 1928, less than nine months later. The cartoon mouse was envisioned as a direct replacement for Oswald the Lucky Rabbit. This time, Disney secured the rights to the character. Mickey, of course, would go on to achieve much more fame—and generate much more fortune—than Oswald.

That said, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit was not a wholly original character himself. He had been created by the Disney Studios in the likeness of another popular animated figure: Felix the Cat. Whitney Matheson, in fact, calls Felix the “feline forefather” to Oswald (par 2). Far from hyperbole, the kinship between the two is apparent. From the physical appearance of Oswald to his trickster personality, Disney was not trying to obfuscate the connection between his animated rabbit and Pat Sullivan and Otto Messmer’s animated cat, he was seeking to capitalize on it. Audiences loved Felix the Cat and, Disney hoped, they would love the similar-looking-and-acting Oswald the Lucky Rabbit just as much. As this early but instructive example suggests, Disney combined innovation with imitation from its initial cinematic ventures. The studio began by taking a character who was not just in existence, but was well-known and successful, and modified the figure in ways that made it their own. Oswald the Lucky Rabbit was like Felix the Cat in many ways, but he was also different in key aspects. Similarly, Mickey Mouse mirrored Oswald, but, obviously, he was also obviously distinct from him.

Dopey participates in this phenomenon. In the same way that the Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm version of “Snow White” forms the basis for the plot of the 1937 movie, R. F. Outcault’s The Yellow Kid forms the basis for its figure of Dopey. The Disney production is both imitating and innovating—or, perhaps more accurately, it is innovating through imitation. Dopey replicates The Yellow Kid while simultaneously constituting his own distinct character. Echoing a trend that goes back to the lineage of Mickey Mouse, the elements of originality in Disney cannot be separated from those of homage. Instead of being contradictory, imitation and innovation are interconnected and even interdependent.

Much has been written over the decades about the cross-pollination that occurred between early newspaper comics and early animation in the United States. Winsor McCay, for example, was a pioneer in both arenas, creating innovative newspaper comics like Little Nemo in Slumberland (1905 – 1927) as well as groundbreaking animated shorts, such as Gertie the Dinosaur (1914). Likewise, the popularity of many stars from early silent animation, like Felix the Cat and Betty Boop, prompted them to appear as newspaper strips. The suggestive echoes between R. F. Outcault’s The Yellow Kid and Walt Disney’s Dopey add a new facet to this phenomenon. The way in which the beloved animated dwarf recalls and reflects the wildly popular comics’ protagonist places these two giants of American cartooning in closer creative and cultural dialogue. Dopey is a nonverbal character in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. However, his physical, sartorial, and behavioral kinship with The Yellow Kid has much to tell us.

Michelle Ann Abate is Professor of Literature for Children and Young Adults at The Ohio State University. She is the author of six books of literary criticism. Professor Abate has also published more than forty peer-reviewed journal articles about a wide array of topics in U.S. children’s literature, popular culture, comics, and LGBTQ issues. Additionally, Professor Abate is the co-editor of five collections of critical essays. Finally, she has written invited pieces for The New York Times and been interviewed for and quoted in articles in The Washington Post and The Boston Globe.

Works Cited

Blackbeard, Bill. R. F. Outcault’s The Yellow Kid: A Centennial Celebration of the Kid Who Started Comics. Kitchen Sink Press, 1995.

Bolton, Jonathan. “Richard Outcault’s Hogan’s Alley and the Irish of New York’s Fourth Ward, 1895 – 96.” New Hiberia Review. 19.1. (Spring 2015): 16 – 33.

Brands, H.W. The Reckless Decade: America in the 1890s. University of Chicago Press, 1995.

Canemaker, John. Before the Animation Begins: The Art and Lives of Disney Inspirational Sketch Artists. Hyperion, 1996.

Finch, Christopher. The Art of Walt Disney: From Mickey Mouse to the Magic Kingdoms. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1975.

Frome, Jonathan. “Snow White: Critics and Criteria for the Animated Feature Film.” Quarterly Review of Film and Video. 30. (2013): 462 – 473.

Gabler, Neal. Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination. New York: Vintage, 2006.

Ghez, Didier. They Drew as They Pleased: The Hidden Art of Disney’s Golden Age, The 1930s. Chronicle, 2015.

Gilbert, Sandra M. and Susan Gubar. The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination. 1979. Yale, 2020.

Giroux, Henry, and Grace Pollock. The Mouse that Roared: Disney and the End of Innocence. Rowman and Littlefield, 2010.

Hammond, Trevor. “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs Released Nationwide: February 4, 1938.” Newspaper.com. 1 February 2016. https://blog.newspapers.com/snow-white-and-the-seven-dwarfs-released-nationwide-february-4-1938/ Accessed 16 June 2021.

Harvey, R. C. “Outcault, Goddard, the Comics, and the Yellow Kid.” The Comics Journal. 9 January 2016. http://www.tcj.com/outcault-goddard-the-comics-and-the-yellow-kid/ Accessed 11 May 2021.

Kaufman, J. B. The Fairest One of All: The Making of Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Walt Disney Family Foundation, 2012.

Lady and the Tramp. Dirs. Clyde Geronimi, Wilfred Jackson, and Hamilton Luske. Perfs. Erdman Penner, Joe Rinaldi, and Ralph Wright. Walt Disney Productions, 1955.

Leuchtenburg, William E. Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, 1932 – 1940. Harper Collins, 2009.

Matheson, Whitney. “Enough of the Mouse What of the Cat?” USA Today. 18 November 2003. http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/life/columnist/popcandy/2003-11-18-pop-candy_x.htm Accessed 19 August 2022.

Meyer, Christina. Producing Mass Entertainment: The Serial Life of the Yellow Kid. Ohio State UP, 2019.

“Mouse and Man.” Time. 30. (27 December 1937): 19–21.

Olson, Richard D. “R. F. Outcault, The Father of the American Comics, and the Truth about the Creation of the Yellow Kid.” http://www.neponset.com/yellowkid/history.htm Accessed 11 June 2021.

One Hundred and One Dalmatians. Dirs. Wolfgang Reitherman, Clyde Geronimi, and Hamilton Luske. Perfs. Rod Taylor, Betty Lo Gerson, J. Pat O’Malley. Walt Disney Productions, 1961.

Outcault, R. F. Hogan’s Alley. New York World. 5 May 1895 – 4 October 1896.

—–. McFadden’s Row of Flats. New York Journal. 18 October 1896 – 23 January 1898.

Pierce, Todd James. “Wow, We’ve Got Something Here: Ward Kimball and the Making of Snow White.” New England Review. 37.1 (2016): 123–136.

Rindskoff, Jeff. “25 Ways Disney Has Revolutionized Entertainment.” Cheapism. 28 September 2018. https://blog.cheapism.com/disney-facts/ Accessed 20 July 2021.

Rosen, Elliot A. Roosevelt, the Great Depression, and the Economics of Recovery. University of Virginia, 2005.

Saguisag, Lara. Incorrigibles and Innocents: Constructing Childhood and Citizenship in Progressive Era Comics. Rutgers UP, 2019.

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Dir. David Hand (supervising director). Perfs. Adriana Caselotti, Lucille Laverne, and Harry Stockton. Walt Disney Studios, 1937.

Susanin, Timothy S. Walt Before Mickey: Disney’s Early Years, 1919 – 1928. Jackson, MS: UP of Mississippi, 2011.

Thomas, Frank and Ollie Johnston. The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation. Disney Editions, 1995.

Yaszek, Lisa. “‘Them Damn Pictures: Americanization and the Comic Strip in the Progressive Era.” Journal of American Studies. 28.1. (April 1994): 23–38.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Gwen Athene Tarbox for calling my attention to this topic, as well as for encouraging me to write this essay.

[1] For more on this era, see Brands.

[2] For more on FDR’s public works programs, see Leuchtenburg.

[3] For more on FDR’s fiscal policies, see Rosen.

[4] For more on the groundbreaking features of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, see both Kaufman and Frome.

[5] For more on the artistic, technological, and narratological innovations pioneered by Walt Disney and his studio, see Thomas and Johnston.