Introduction

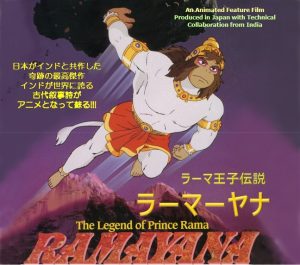

In February 2019, a few months before the Covid-19 pandemic outbreak, the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) organized a two-day event, the Indian Gaming Show, which took place at Pragati Maidan, New Delhi. The event showcased the latest developments in the Indian video gaming industry and hosted international representatives of gaming and animation industries from around the world. The Japanese delegation was the most prominent foreign group at the event, maintaining an extensive Pavilion. Putting on view ample gaming- and animation-related features, the Japanese Pavilion also installed an exhibition stand commemorating a somewhat forgotten full-length animated work, Ramayana: The Legend of Prince Rama (Rāmayāna: Rāma ōji densetsu, dir. Ram Mohan and Yugo Sasaki). Promoters of the animation marketed it as an Indo-Japanese coproduction. Still, in fact, the vast majority of the high-level professionals involved in the production were Japanese and had worked on it entirely in Japan. It is perhaps for this reason that, while scholars such as Timothy Jones (59) do recognize the production as India’s first feature-length animated work, others (arguably most) credit Hanuman (dir. V. G. Samant, 2005) as the first “real” feature-length animation.[i] Be that as it may, this essay argues for the inclusion of the animated work not just in the history of Indian animation (whether as the “first” or otherwise), but also in the larger context of the Ramayana epic and its multimedia adaptations.

The Legend of Prince Rama debuted at the Delhi International Film Festival in January 1993 and then traveled to other film festivals, including the International Children’s Film Festival in Udaipur, also in 1993. However, unfavorable social and political circumstances prevented its wider commercial theatrical release. It was not until September 2018 that a small Japanese theater in Yokohama released it for the first time. Between its premiere and the first commercial release, the animated production was only sporadically shown in film theaters, and most viewers watched it on television, mainly in India, where it was broadcast on Channel 18 every Diwali and, more frequently, on Cartoon Network (Pandyan 83).

In the following sections, I discuss elements of the animation’s production and its style, and contemplate possible reasons for its relative (unjustified) obscurity. In this manner, I aim to resituate the animated work within the ever-expanding context of the sacred Hindu text, the Ramayana, while addressing issues bound up with mythology, reality, originality, and nationality. Lastly, I conclude by drawing attention to the fact that the completion of the project, like most Japanese animated productions, relied heavily on non-Japanese animation studios in Eastern and Southeast Asian countries. In this context, however, given that the work’s inspirational birthplace is in India and not in Japan, I argue that The Legend of Prince Rama signals a kind of reversed outsourcing, rendering the production location, as well as its nationality (or indeed, transnationality), less consequential. Instead, the work’s source or origins is the mythological text itself, and despite hesitations to label it “India’s first animated work,” it certainly affiliates with India, and thus should ostensibly be thought of at the very least as India’s first and only (to date) animé.[ii]

Producing a Legend

Sakō Yūgō[iii] (1928–2012) envisioned this project as early as 1968, after reading a Japanese translation of the epic. Between that first reading and the realization of his vision, he produced and directed several television documentaries on India for a number of Japanese TV networks. After completing his last documentary, assisted by archeologist Braj Basi Lal, about suspected relics of the Ramayana as a “beautiful myth,” he began taking practical steps toward materializing his animation vision. However, the project was delayed due to a few setbacks, such as a Hindutva group (Vishva Hindu Parishad) that warned the Japanese embassy in New Delhi against attempting to create a new interpretation of the sacred text. It appears as if their warning was based on an article in the Indian Express, one of India’s leading national dailies, published on April 25, 1983, suggesting that Sakō’s earlier TV production in India was not a documentary, but a Japanese effort to recreate the Ramayana.

Sakō persisted, and although he did not have any expertise in animation, he speculated that the epic’s fantastical elements and the strength of the Japanese industry would make animation the right medium for adaptation. He also calculated that the medium’s common perception as susceptible to dubbing would facilitate catering most effectively to the widespread population around Asia and diasporic communities, as well as to introducing the epic to Japanese viewers who were less familiar with it. Thus, despite little to no practical knowledge about producing animation, Sakō was determined to create a full-fledged animated adaptation.

Cautious about religious sensitivities, however, Sakō wanted the work to be coproduced by both India and Japan, using the former’s claim for the text as its heritage and the latter’s prowess in the field of animation. On a practical note, too, he hoped to more easily secure funding from two countries instead of one. Although several Indian businessmen, including producer S.S Oberoi, did show an initial willingness to invest in the project, in the end, funding for the production, rumored to be as high as 800 million yen, was exclusively Japanese.[iv]

Accordingly, the vast majority of the 450 personnel recruited for the project were Japanese, including the de facto director, Sasaki Kōichi. Yet, under Sakō―whom the film also credits as a co-director, although he acted solely as an executive producer―several Indian artists helped shape the film’s form. Chief among them was Ram Mohan, an Indian governmental 2014 Padma-Shri-award recipient for his contribution to Indian animation. He is commonly recognized as the “father of Indian animation.”[v] Mohan had a decisive role in the characters’ design, as well as general stylistic aspects. Other highly influential contributors were writer Pandit Narendra Sharma, composer Vanraj Bhatia, and lyricist Vasant Dev, who wrote the film’s songs. The production recorded the soundtrack and produced the original English dubbing in Mumbai, with local voice actors. Mumbai-based playback singers also recorded the songs in the purported Indian film capital. Sakō later arranged a recording of new soundtracks in Hindi, for North Indian theatrical releases, and in American English, for global and North American markets, where it eventually circulated mainly on VHS tapes and later on DVDs.

The film was hand-drawn using the cel animation process. Most of the artists were Japanese, working at the production headquarters in Tokyo. However, as is often the case in Japanese animation, the producers also outsourced portions of the labor to different animation studios in Japan; some of these, particularly Dōga Kōbō and Emuai, relied on foreign studios in Indonesia and South Korea.[vi] Any arguments for the Japaneseness, as well as the Indianness of the project should, therefore, be equally contested. The animation’s ad hoc production company, the Nippon Ramayana Film Committee, headed by executive producer Matsuo Atsushi, had, over the years, considered a Japanese-dubbed version. However, as critic Masutō Tatsuya states in a relatively recent article for Kinema junpō, Japan’s longest-running film magazine, such a version does not yet exist. Notably, he discursively associates the animation’s first Japanese theatrical release with that of the South Indian films Muthu and Baahubali 2: The Conclusion, which attracted many Japanese to film theaters (Masutō 107). Thus, despite largely being a Japanese production, in Japan, it is publicized as an Indian cultural phenomenon.[vii]

The Tale of Rām

Despite its relative unfamiliarity in Japan, the epic Rāmāyaṇam is well-known throughout most of Asia and the wider world. Even non-Hindus, particularly in the Indian subcontinent, are commonly familiar with the basic narrative, as they have been exposed to it through myriad media adaptations and retellings of portions of its main storyline. There are also several versions of the narrative itself, each one deviating, to some extent, from the Sanskrit text attributed to poet Vālmīki.

Ramayana: The Legend of Prince Rama credits Valmiki as the film’s original source, but the ending, in particular, seems to more closely follow other retellings, such as Tulsidas’ Rāmacaritamānasa. For instance, the name of Valmiki’s hero was altered from the Sanskrit Rāma to Tulsidas’ Hindi version of Rām (henceforth, Ram). In an early article about the project, before the work had begun, journalists reported that the head scriptwriter, Pandit Narendra Sharma, preferred Valmiki’s version because it depicts Ram more as a human than as a god (Grewal and Nasta 75). However, the treatment of the epic is not necessarily bound to any specific version. The main narrative in both versions, as well as the animation, is rather similar. In short, Ram, who is about to be anointed as Ayodhya’s king, wins a contest and is allowed to marry the beautiful Sītā (henceforth, Sita). However, shortly after the nuptials, they are forced into exile. Ram’s devoted brother, Laxman, departs with them. They live in a forest, where, one day, Sita is kidnapped. The brothers search for her, and along the way, they befriend a magical monkey who soon becomes one of Ram’s most loyal devotees. Together, and later joined by a whole army of monkeys, they wage war against the kidnapper, Rāvaṇa (Rāvaṇ in Hindi; henceforth, Ravan), the ruler of Lanka (traditionally identified as the current Sri Lanka). They win, and the married couple is reunited. They then ride on a flying chariot back to Ayodhya, where the narrator announces they will live happily for a few years, until Ram returns to the sky and Sita to the earth, hinting at the more controversial ending in Valmiki’s Sanskrit epic, in which Sita is forced to prove her chastity by stepping into fire.

Unlike any of the long textual versions of the epic, however, the animated adaption flattens most of the tale, shifting the events quickly from one to another, without much attention to the protagonists’ psychology or emotional state. Due to its limited duration, it only hastily depicts interactions between the characters and places, whereas most of the emphasis is on the action. Dialogue is scarce and nearly half of the work is a detailed and prolonged final war sequence. As such, one might argue that rather than fidelity to the poetics of the South Asian text, the animated adaptation seems more faithful to its adoptive Japanese medium and its famed two-dimensional expressive mode.

Ramayana’s Mythological Remixes

Notwithstanding the claim made here about the innovation generated by animating the revered Hindu text, it adjoined an ever-expanding corpus of renditions. At the opening of his seminal study of Ramanand Sagar’s television series adaption of the Ramayana, Philip Lutgendorf cites the following line from Tulsidas’ version of the epic: “Ram incarnates in countless ways, and there are tens of millions of Ramayans” (127). A. K. Ramanujan counts “only” 300 versions (22-48), but whatever the number might be, variations certainly abound in many vernaculars. In addition, Victor H. Mair notes the adaptions in numerous media and genres, including statues, short stories, songs, puppet shows, poems, pageants (Rāmlilā), paintings, dances, plays, novels, movies, television shows, and many others (664-665). Furthermore, in a separate publication, Lutgendorf introduces the notion of a “Ramayana remix” to refer to audiovisual works that, albeit not directly depicting or retelling the epic, provide indirect commentary on it (2010, 145-54). No scholar, to my knowledge at least, has yet seriously contemplated accounting for animation within the “Ramayana mix.” However, in anticipation of one of The Legend of Prince Rama’s screenings during its initial 1993 subcontinental tour, Dilip Joshi hinted at that possibility. Writing for the Marathi edition of the weekly news magazine Chitralekha, Joshi celebrated the coming event as a “Ramayana animation avatar,” or a reincarnation of the epic in animation form.

Popular films based on the epics of the Ramayana and the other great Sanskrit epic, the Mahābhārata, usually fall into what Chidananda Das Gupta calls the “mythological genre.” Gupta states that most of the films produced in India’s pre-talkies era pertain to this genre, including what is considered India’s first film, Dadasaheb Phalke’s Harischchandra (1913)―a common historical statement that might be disputable (Gupta 1989, 12). Ashish Rajadhyaksha and Paul Willemen, along with other scholars, maintain that the crowning of India’s first film was grounded less on facts than on the availability of prints, scholarly material, and the director’s adherence to national/independence movements, whereas the bonafide first film might actually be the 1912 devotional film Pundalik, which is attributed to N.G. Chitre, P.R. Tipnis, and Ramchandra Gopal Torney (18). At any rate, according to Rachel Dwyer, Phalke’s most popular silent film was Lanka dahan (1917), a film that depicts a portion of the Ramayana (23). Other notable points in the epic’s lineage of cinematic adaptations include Vijay Bhatt’s two talkie versions, Bharat Milap (1942) and Ram Rajya (1943),[viii] followed by Babubhai Mistry’s 1961 longer version Sampoorna Ramayana.

According to scholars such as Dwyer and Gupta, one of the pleasures for Hindu believers in watching mythological filmic adaptions is seeing the epic in motion as the text comes to life. Scholars also point out that the very act of “seeing” for Hindus, at least among devotees, differs significantly from the secular ways of visually appreciating motion pictures. Rather than simply watching, viewers are seen to engage in worship practices such as puja, but mainly darśana, which refers to an auspicious visual exchange between the believer and sacred deities.[ix] Probably because mythological animation is still a relatively new (compared with live-action film, for example) phenomenon in India, there is little discussion of “seeing” with regard to this medium. Scholars do, however, discuss the applicability of the term in the context of a closely-associated medium: graphic novels or comics.[x] Most notable in this regard is Anant Pai’s Amar Chitra Katha (Immortal Picture Stories, serialized since 1967), a graphic novelization series of historical figures, mythologies, epics, and folk stories.

In Japan, notably more than in India, comics, or manga, as they are referred to domestically and globally, are immensely popular. It is debatable whether premodern manga and its modern reincarnation can be discussed under the same category, but scholars seem to agree that in its modern form, manga probably appeared in the late nineteenth century.[xi] Given this long history and the enormous number of publications, it is not surprising that, either directly or indirectly, some manga deal with Japanese religious and mythological themes. However, such publications are few and far between in the wide spectrum of the Japanese manga industry. Tezuka Osamu, who is commonly known as the “father of manga,” published some of the most striking exceptions in this regard, including Buddha (1972–1983) and several early chapters of his unfinished work Hi no tori (Phoenix, 1967–1988). Portions of both of these series were also adapted into animation, and Ichikawa Kon directed a 1978 live-action film based on the first book of the Hi no tori series, in which he also incorporated animated sequences.

Unlike the rich Hindu mythological epics, Japan’s two main collections of myths, the Kojiki and Nihon shoki, were compiled relatively late (during the eighth century AD). While the tales they depict are much older, and while there are other Japanese mythological tales, none has ever provided a particularly attractive source for popular modern media content. Inagaki Hiroshi has arguably directed the only film that could fall into a Japanese mythological category, The Birth of Japan (Nihon tanjō, 1959), and in terms of animation, the children’s episode in the Doraemon franchise, Nobita and the Birth of Japan (Shin Nobita no Nippon tanjō, dir. Yakuwa, 2016) is probably the only well-known work.[xii] Due to this scarcity, scholarly works on representations of Japanese mythology focus mainly on indirect depictions, associated themes, ambiguous or tentative links to Japan’s ancient history, or prehistoric tales.[xiii]

As Roland Barthes famously contended, the distinction between history and mythology could be a matter of inflection, rather than a distinction between fact and fiction (128). That is to say, at least from the perspective of semiotics, myths do not fictionalize true events, nor do they obscure reality. Instead, they present, according to Barthes, a third way that enunciates a compromise between fiction and reality. Seen in this light, the media perspective on mythology in both Japan and India is not necessarily as remote as one might think. The semblance between the two, however, is not a reference to mythological narratives through theories of cosmopolitanism or universalism by scholars such as Joseph Campbell or Claude Lévi-Strauss, but a nod to the affect within a constellation of narratives circulating amongst consumers of cultural or media products. In this sense, appreciation for the animated Ramayana in both India and Japan can be thought of in tandem, along the lines of domestic propensities that equality converge in the global (although not uniform) process of the “Ramayana mix.” In other words, the myth becomes a compromised space, not just between text and subtext, or truth and fiction, but also between the two geopolitical entities, as well as cultural and medial sources.

Specifically, in the Japanese context (or media ecology), in addition to local historical sources, animators often adopt stories, folk tales, and mythologies from other parts of the globe into distinctly Japanese animation, or animé (henceforth, anime). In fact, Japan’s first feature-length postwar animation, Panda and the Magic Serpent (Hakujaden, dir. Taiji Yabushita, 1958), was based on a Chinese setsuwa, a classical or medieval tale.[xiv] The 1960 feature Saiyūki (distributed in the West as Alakazam the Great, dir. Daisaku Shirakawa and Taiji Yabushita) was also based on a Chinese source, one that some like the aforementioned scholar Victor H. Mair speculated might actually be partially influenced by the Ramayana epic. The main character in the film, Son Gokū (or Sūn Wùkōng, in Chinese vernaculars), is believed to be modeled on Hanuman, one of the main characters in the Ramayana. Similarly, both are human monkeys who boast special abilities, like flying and morphing into different sizes or shapes. Son Gokū is also the source of much earlier short animations in Japan, like The Story of the Monkey King (Saiyūki: Son Saiyūki monogatari, dir. Noburo Ōfuji, 1926), as well as many other works in various media, including live-action films, television dramas, manga, and TV animation spinoffs, of which the Dragon Ball franchise is probably the most well-known.

As Thomas Lamarre points out, cute monkeys also had a more ominous use in animation during World War II (75-95), and even after the war, depictions of race or non-Japanese ethnicity remained an area of contention.[xv] However, after the war, Japanese animators often depicted nonhuman characters in a favorable fashion, whereby ethnic or national identity has been largely transformed into an unspecified notion of cuteness (kawaii).[xvi] That is, animated depictions of pets, and even wild animals, similar to those of young boys and girls, have largely been shown as innocent, inherently friendly or trustworthy, and thereby as more attractive characters. As Lamarre emphasizes, this is the case not only in Japan but in animation in general, wherein a certain degree of affection is “associated with animated animals” (79). While he exemplifies what he calls animals and “kinetophilia” in terms of movement or plasticity, mainly in pre- and inter

war Japanese animation, it can be argued that despite numerous exceptions, the tendency is even more pervasive in the postwar era. It is therefore not surprising that, along with the introduction of the Ramayana epic, Japanese newspaper articles about the Ramayana animation highlighted Hanuman’s role and linked him with Son Gokū. For instance, the subtitle for a 1993 Mainchi Shimbun article about the film was “Visualizing [eizōka] India’s National Cultural Treasure: Son Gokū’s Roots” (Nagaoka79). A pamphlet (chirashi) of the film distributed at a Yokohama theater even added a speculation that the Ramayana may have influenced the Japanese folk tale about Momotarō (Peach Boy).

The animated Ramayana was therefore not simply thrown into a void within the Japanese domestic media ecosystem. Moreover, there were other possible supporting aspects that could have bolstered the production’s reception in Japan. Among them are Indian mythological themes featured in several media products such as Ōkawa Nanase’s manga series Seiden: Rigu Vēda (RG Veda, 1989–1996), which was based on Vedic mythology and was adapted into two original video animations (OVA) in 1991 and 1992. Moreover, famed animator Oshii Mamoru’s first video game Sansara naga (1990), too, centers on prehistorical Indian imagery.

Paradoxically, growing interest in Indian culture may have contributed to the failure to find a local distributor for the animated Ramayana project in 1990s Japan. While Indian mythology (no matter how loosely conceived) was a source for media content in the late 1980s and early 1990s, public opinion on the matter changed dramatically after the 1995 Tokyo subway sarin attack. The group that carried out the attack, Aum Shinrikyō, associated itself with some aspects of Hinduism and, as news outlets reported, its leader, Asahara Shōkō, had frequently traveled to India for alleged spiritual retreats. Moreover, some of the religious organization’s materials, including especially its animated series Chōetsu sekai (Transcendental World, credited to Asahara) and manga Supirittuaru janpu (Spiritual Jump) showcase features that some in Japan may find to resemble Indian mythological comics and even The Legend of Prince Rama’s style. For example, the following images might be perceived by non-experts in Japan as similar forms of Hindu meditation.

In India, where religious tensions often loom large, the timing was even worse: just a few weeks before the film’s premiere, riots ensued in Ayodhya, resulting in the destruction of the Babri Masjid mosque and raising fears of a full-scale religious war (Bacchetta 255). The wide release of an animation celebrating pre-Muslim/Mughal Ayodhya might have caused more friction.

While the circumstance that hampered a wider release in India at the time may have been religious or political, in Japan, there was another crucial problem. In general, Japanese film theaters screen foreign films in the original language, with Japanese subtitles. With regard to animation (including Disney films), however, audiences are accustomed to dubbing; without a Japanese version, the film remained inaccessible or unappealing to most potential viewers.

The reviews after the first screening in New Delhi were positive, however. Writing for the Mainichi Shimbun, one of Japan’s major newspapers, Yamanishi Kazuo reports that one viewer wanted the film to raise awareness of the importance of human love and different people living together. Going even further, Suresh Saanvat of the Navbharat Times praises the film and writes that, despite being a Japanese creation, it is nonetheless a full and beautiful Indian mythological (pauranik) work. These views, along with the overall positive reception, demonstrate the domestic and transnational appropriation of the animated work into the process that Lutgendorf identifies as a “Ramayana mix.”

Ramayana: The Anime

Writing for The Hindu newspaper on September 26, 2002, just before telecasting of the then relatively new Hindi-dubbed version of The Legend of Prince Rama began on Cartoon Network, Kannan K. states that the film’s style showcases a “fusion of the manga school of animation and the artistic style of Ravi Verma.” Although there is no single “manga school,” as mentioned already, it is undeniable that manga, or Japanese comics, has influenced Japanese animation.[xvii] Moreover, given that this feature, like most Japanese anime, reflects a wide range of influences, styles, and designs, the reference to the renowned Indian painter, Raja Ravi Varma (1848–1906), is rather peculiar. Presumably, the critic meant to situate the otherwise strikingly Japanese visual work within an Indian media context, much like other commentators in Japan and India aimed to do during the initial theatrical screenings period. However, despite not singling out television as a medium in his commentary, Kannan K. nonetheless marks a new stage in the evolution of the animated work in the “Ramayana mix” process, one that now includes a televisual reincarnation.

Regardless of the national and media-hybrid aspects that characterize the work, its visual features anchor the narrative in a specific Indian space. Such spatial specificity is marked right from the first frame, with an image of a seemingly archaic topographical map of the subcontinent. This is expected, perhaps, since much of the Ramayana is about its protagonists’ journey through this geographical location. Chetan Desai’s slightly shorter digital 2010 animated adaptation Ramayana: The Epic also features such a map, but it is a bit more cartoonish and less realistic topographically. Unlike the Legend of Prince Rama, Desai uses the map to show the trajectory of the protagonists on land, in addition to a narration that introduces locations of importance along the journey. In contrast, the Legend of Prince Rama displays the map only once, as a totality of space that cannot be divided. When Ram and Laxman arrive at certain locations, the name of each place is announced in the text inscribed on the frame, without any narration. This might signal a disregard for viewers less familiar with India’s topography, but it also marks an overarching emphasis not on India as a historical geopolitical entity, but as a site that ultimately transcends time and space.

The next indication of the film’s artistic affiliation comes with the proceeding frames, which present a series of elaborate still paintings. Drawn by art director Matsuoka Hajime, these are faintly colored, but painstakingly crafted independent creations that seem to mimic relief sculpture. The first one depicts Ram’s nemesis, Ravan, and the next ones portray other characters as an introduction to the epic. Framing segments of the film via another medium is a well-known practice, although usually, it is the animation that augments live-action films, as is the case in such Japanese films as Koi ya koi nasuna koi (dir. Tomu Uchida, 1962). Ram Mohan himself even contributed animation sequences to several non-animated films, including Bhuvan Shome (dir. Mrinal Sen, 1969). In both of these cases, the use of animation was likely either due to limited access to cinematic special effects, or economic constraints. It is probably a matter of practicality for the Legend of Prince Rama to provide the epic’s background with still images that then set the film in motion. In painstakingly recreating non-animated still paintings, the animation projects adherence to a well-anchored real-life location. However, as mentioned already above, rather than painting as such, the opening still images refer to a unique Indian type of relief sculpture (often known as mid- or half-relief).

Unlike other kinds of sculptures, relief ones seem raised from the ground, rock, or a structure to which they are inherently attached. The same is true of the animation, which projects features of the epic while, at the same time, confirming its subordination to the living text and the place of its birth.

Specifically, regarding the aesthetics of Indian relief sculptures, Alice Boner writes:

The scape-direction embodied in the diameters and their parallels are the vital nerve-lines of these compositions. They create currents of energy that run either parallel to or across each other in their trajectory, that act and react upon one another in various ways according to their position in space, that is to say, their position in the relief-field. These life-currents transform a composition into a functional organism. The forms animated by them become functional stresses, and an image conceived on such a pattern will never be a static configuration, even if the single figures represented are at rest. The current of energy circulating within them will ever be at work and animate their forms (24-25)

Similar energy to the one that animates the form in Boner’s description is also at work in The Legend of Prince Rama’s opening segments. The camera moves in and out of the still images, pans to the sides, and tilts up and down over them. By doing so, the camera reveals more of the images in accordance with the narration, manifesting a certain aesthetic economy. The animation that follows is much richer and arguably should fall into a category of full, rather than limited. The animators, however, employ a similar mode of movement from the opening to sequences throughout the work, and it is most pronounced during the song sequences. For example, this is evident in the establishing frame in the “Forest of Panchwati” song scene (a feature more common in Indian popular cinema, as well as, perhaps, Disney, but not in Japanese animation). Here, the animators begin with a short but complex movement form, whereby the camera moves on the surface, and, at the same time, the different layering of the characters moves as well. Next, the camera tilts up from a body of water, parallel to still bushes and a tree, and continues with an elevation move into the sky, which is concluded with a cut to Sita in a medium shot. Following several other motionless short takes, the camera starts to move again across the background of the sky, left to a tree, and then down its trunk. This artistic regime is established already in the film’s opening, with the introduction of the epic over the relief-like painting.

The animated motion techniques described above are not unique to this work. Similar styles are common among Japanese animators, most notably in works by Studio Ghibli and its long-time chief animator, Miyazaki Hayao, who insists on using the anachronistic term manga eiga or manga film to categorize his work (Lamarre 35). Thomas Lamarre names this overarching oscillation between full and limited animation in Miyazaki’s work and that of other Japanese animators “limited full animation” (184). In addition to this amalgam of the typical Japanese anime style (albeit with new Indian characteristics), several commentators online stress the characters’ facial features, especially the eyes, as ostensibly manga-like. While eye design does seem to share much affinity with other Japanese animated works, it is markedly different from that seen in Studio Ghibli’s so-called manga films such as Castle in the Sky (dir. Hayao Miyazaki, 1986), Grave of the Fireflies (dir. Isao Takahata, 1988), My Neighbor Totoro (dir. Hayao Miyazaki, 1988), and Kiki’s Delivery Service (dir. Hayao Miyazaki, 1989), which showcase large roundish-shaped eyes. Instead, the similarity is registered more closely with considerably more aggressive, even violent works, or those catering to mature audiences, including Wicked City (dir. Yoshiaki Kawajiri, 1987), Akira (dir. Katsuhiro Ōtomo, 1988), Patlabor: The Movie (dir. Mamoru Oshii, 1989), and Ninja Scroll (dir. Yoshiaki Kawajiri, 1993), where animators designed more sharp-looking eyes. Yet, unlike these risqué animated works, which also depict stern facial expressions, with the exception of the eyes, the protagonists’ faces in The Legend of Prince Rama are soft, and more in tandem with children’s animation.

The animation’s overall style, therefore, albeit featuring unquestionable Japanese characteristics, is unique within animated works of that period. Moreover, unlike other works, The Legend of Prince Rama is marked by its emphasis on action, motion across the frame, composition of movement within frames, minimal dialogue, as well as the uncommon use of voiceover narration. As such, it delivers a visceral experience and an intense visual absorption into a different realm of animated epic-telling, one that emphasizes emersion in lieu of a plot-centric approach.

Conclusion: Reversed Outsourcing

Animators in Japan constantly look for more sources on which to base new works. They either directly adapt foreign narratives or indirectly incorporate such stories into their plotlines. Yet, through the process of adaptation, animators, inadvertently or not, also appropriate foreign culture into the anime universe. According to theorist Azuma Hiroki, the anime world of the 1980s and early 1990s, in particular, maintained its own postmodern reality, which he calls a “database” (31-33). Marc Steinberg evokes Roland Barthes’ Mythologies to explain that Azuma’s model represents a naturalization of (social or cultural) codes to interlink anime and comics (manga) as a foundation of a new reality (294). In this world, anime consumers reject grand narratives in favor of characters, especially cute ones (kawaii), such as shōjo or young girls that produce a visual pleasure that Azuma calls kyara-moe, an affective response to characters. As for this world’s market logic, Steinberg delineates it around the concept of media-mix that channels different media flows, as well as merchandising products.

The Legend of Prince Rama is an anomaly in the anime world. Not only does it feature no characters in the form cherished in the anime database, but it even goes so far as to dismiss such notion by its faithful attachment to a profoundly grand narrative: the Ramayana. The film then also underscores a stark contrast to films such as Sita Sings the Blues (dir. Nina Paley, 2010), which projects a new subversive adaption of the Ramayana not just in media terms, but also more so in terms of narrative. Alternatively, the Legend of Prince Rama refrains from literally or textually interpreting the epic in new ways and instead veers towards reanimating it, or toward visualizing the text while expressively affirming the limitations of the medium within which it does so. Despite its limited theatrical releases and the more prominent television run, the animation does not adhere to the media-mix model, but rather to the Ramayana-mix one. As such, instead of a commercial rationale, the animated work leans more heavily toward artistic, cultural, as well as spiritual or religious outreach.

As for the work’s nationality, or its affiliation with a specific nation-state, it appears that neither India nor Japan could exclusively claim it, and neither can one offer to the other as a gesture of goodwill.[xviii] While most of the production is Japanese, it is an outlier within the Japanese anime world. In addition to the absence of a Japanese language version, even the subtitled version presents comprehension difficulties for the average Japanese viewer. The original dialogue uses Sanskrit terms, such as Kshatriya (kṣatra, warrior class), shanti (inner-peace), jai (as in jai Ram!, which is translated in the subtitles rather creatively into Japanese as banzai), and more importantly, dharm. The last is the Hindi pronunciation of dharma, a key term in Hinduism, and also a crucial component in the film. However, the concept is largely unfamiliar in Japan, where its common transliteration is daruma, and while the subtitles do, at one point, refer to it as “obligation” (gimu), the spiritual dimensions of the film are essentially closed for most Japanese speakers. On the other hand, the film caters to South Asians with much greater ease, and despite its affinity with other Japanese animated works, given the lack of full-length Indian precedents at the time of its completion, it could as easily be interpreted as an original Indian re-animation of the epic.

As it pertains to the realm of the myth in Barthes’s terms, The Legend of Prince Rama positions itself in a semantic evasive nonaligned space. It belongs neither to a single geopolitical origin nor to a discrete media ecology. At the same time, however, as a production that negotiates these two unmistakable sources, The Legend of Prince Rama manifests itself as a product of what I call a reversed outsourcing. Rather than capitalizing on an affiliation with a given medium or cultural source, the animated adaptation showcases a liminal process away from any claims for originality, media boundaries, or national thresholds.

Thus, while contemporary distributors are at pains to promote the work as a transnational collaboration or Indo-Japanese coproduction, The Legend of Prince Rama diverges into two distinct media ecologies: one that can easily sustain its wide circulation and one that cannot do so. Seen in this light, The Legend of Prince Rama is not only another augmentation to a perpetually expanding “Ramayana-mix”; given its concurrent emergences from a multitude of sources, it eloquently converges into what can be labeled an original Indian anime.

Rea Amit is assistant professor in the Department of Modern Languages, Literatures and Linguistics at the University of Oklahoma. He holds a Ph.D. in Film and Media Studies and East Asian Languages and Literatures from Yale University, and an MA in Aesthetics from Tokyo University of the Arts. He has published mainly on Asian media, aesthetics, and theory in journals such as Philosophy East and West, Positions, Participations, and On_Culture, as well as several book chapters in edited volumes.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Timothy Jones for an early review of the article, and for referring it to Animation Studies. I am also in debt to Sasaki Yōko who shared with me firsthand resources to base this article on, as well as other unreleased information about the production and the people involved with it. The current article version also benefited from comments by two anonymous referees, as well as careful editorial work and insights by Mihaela Mihailova.

Works Cited

Amit, Rea. “On the Structure of Contemporary Japanese Aesthetics.” Philosophy East and West, Vol. 62, No. 2, 2012, pp. 174-185. https://doi.org/10.1353/pew.2012.0016

—. (2017). “Shall we dance, Rajni? The Japanese cult of Kollywood.” Participations: International Journal of Audience Research, Vol. 14, No. 2, 2017, pp. 636-659.

Azuma, Hiroki. Otaku: Japan’s Database Animals. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009.

Bacchetta, Paola. “Sacred Space in Conflict in India: The Babri Masjid Affair.” Growth and Change: A Journal of Urban and Regional Policy, Vol. 31, No. 2, 2002, pp. 255-284. https://doi.org/10.1111/0017-4815.00128

Barthes, Roland. Mythologies. Trans. Annette Lavers. New York: Noonday Press, 1991.

Boner, Alice. Principles of Composition in Hindu Sculpture: Cave Temple Period. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1962.

Brown, Noel. “A Brief History of Indian Children’s Cinema.” Family Films in Global Cinema: The World Beyond Disney. I.B. Tauris, 2015.

Dwyer, Rachel. Filming The Gods: Religion and Indian Cinema. New York: Routledge, 2006.

—. “Bollywood’s India: Hindi Cinema as A Guide to Modern India.” Asian Affairs, Vol. 41, 2010, pp. 381-398. DOI: 10.1080/03068374.2010.508231

Grewal, Malvinder, and Nasta, Dipak. “Ram! Ram!!” Showtime, November, 1986, pp. 70-75.

Gupta, Chidananda Das. “Seeing and Believing, Science and Mythology: Notes on the ‘Mythological’ Genre.” Film Quarterly, Vol. 42, No. 4, 1989, pp. 12-18.

Hu, Tze-yue G. Frames of Anime: Culture and Image-Building. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2010.

Ito, Kinko. “A History of Manga in the Context of Japanese Culture and Society.” The Journal of Popular Culture, Vol. 38, No. 3, 2005, pp. 456-475. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3840.2005.00123.x

Jaggi, Ruchi. “An Overview of Japanese Content on Children’s Television in India,” Media Asia, Vol. 41, No. 3, 2016, pp. 240-254.

Jones, Timothy Graham. Animating Community: Reflexivity and Identity in Indian Animation Production Culture. 2014. University of East Anglia, Ph.D. dissertation.

Joshi, Dilip. Chitralekha. April 13, 1992.

Lamarre, Thomas. “Translating Races into Animals in Wartime Animation.” Mechademia, Vol. 3, No. 1, 2008, pp.75–95. https://DOI:10.1353/mec.0.0069

—. The Anime Machine: A Media Theory of Animation. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2009.

Li, Michelle Ilene Osterfeld. Ambiguous Bodies: Reading the Grotesque in Japanese setsuwa Tales. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2009.

Lutgendorf, Philip. “Ramayan: The Video.” TDR, Vol. 34, No. 2, 1990, pp. 127-176. https://doi.org/1146030

—. “Is There an Indian Way of Filmmaking?” International Journal of Hindu Studies, Vol. 10, No. 3, 2006, pp. 227-256.

—. “Ramayana Remix: Two Hindi Film-Songs as Epic Commentary.” Ramayana in Focus: Visual and Performing Arts of Asia. Gauri Parimoo Krishnan (ed). Singapore, Asian Civilizations Museum, 2010, pp. 144–154.

Mair, Victor, H. “Suen Wu-kung = Hanumat? The Progress of a Scholarly Debate.” Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Sinology. Taipei: Academia Sinica, 1989, pp. 659- 752.

Masutō, Tatsuya. “Giganisshi.” Kinema junpō, October 15, 2018, p. 107.

McLain, Karline. “The Place of Comics in the Modern Hindu Imagination,” Religion Compass, Vol. 5, No. 10, 2011, pp. 598-608.

Mōri, Yoshitaka. “The Pitfall Facing the Cool Japan Project: The Transnational Development of the Anime Industry under the Condition of Post-Fordism.” International Journal of Japanese Sociology, Vol. 20, No. 1, 2011, pp. 30–42

Nagaoka, Noboru. “Nichi’In gasaku no Rāmāyana monogatari ga kansei.” Asahi Shimbun Weekly AERA, November 3, 1992, p. 79.

Okuyama, Yoshiko. Japanese Mythology in Film: A Semiotic Approach to Reading Japanese Film and Anime. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books, 2016.

Onoda, Power Natsu. God of Comics: Osamu Tezuka and the Creation of Post-World War II Manga. Jackson: The University Press of Mississippi, 2009.

Pandyan, Kanakasabapathy. “The Coming of Age of Indian Animation.” Journal of Asian Pacific Communication, Vol. 23, No.1, 2013, pp. 66-85.

Rajadhyaksha, Ashish, and Willemen, Paul. Encyclopedia of Indian Cinema. London and Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn in Association with the National Film Archive of India, 1999.

Ramanujan, A. K. “Three Hundred Rāmāyaṇas: Five Examples and Three Thoughts on Translation.” Many Rāmāyaṇas: The Diversity of a Narrative Tradition in South Asia. Paula Richman (ed). Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991, pp. 22–48.

Roy, Piyush. “Editorial: Celebrating a Century of Indian Cinema – Passions, Pleasures & Perceptions.” The South Asianist, Vol. 2, No. 3, 2013, p. 4-8.

Steinberg, Marc. “Realism in the Animation Media Environment: Animation Theory from Japan.” Animating Film Theory. Karen Beckman (ed.). Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014, pp. 287-300.

[i] For instance, see Brown (2015, 196).

[ii] In terms of style, another possible candidate might be Rajorshi Basu’s 2017 film Karmachakra.

[iii] Japanese names appearing in this article follow the Japanese convention of family name, given name order.

[iv] See online sites such as the active Facebook group page: https://www.facebook.com/Ramayanajp/

[v] For instance, see Roy (2013, 6).

[vi] On outsourcing in the context of Japanese animation, see Mōri (2011, 30–42).

[vii] On the reception of Indian films in Japan, see Amit (2017, 636-659).

[viii] As Dwyer notes elsewhere, this version was even appreciated by the otherwise cinephobe Mohandas Gandhi (2010, 394).

[ix] For example, see Lutgendorf (2006, 231–232).

[x] For example, see McLain (2011, 598–608).

[xi] For example, see Ito (2005, 462–463).

[xii] Interestingly, Ruchi Jaggi points out that an earlier Doraemon film was among the most popular on Indian television. See Jaggi (2016, 247).

[xiii] For example, see Okuyama (2016).

[xiv] On the concept of setsuwa, see Li (2009, 15).

[xv] For a specific critical analysis of the Chineseness of Hakujaden, see Hu (2010, 83–95).

[xvi] On this term as an aesthetic concept, see Amit (2012, 178-180).

[xvii] Japanese terminology too sometimes ties the different media, manga and animation, for example, with concepts such as manga eiga (cartoon film) or terebi manga (TV animation). In this regard, for instance, see Onoda (2009, 6).

[xviii] Several media outlets in India depicted the latest release of the animated feature as a special Japanese gift to India. For example, see: https://www.edules.com/2022/01/06/japans-special-gift-to-india-on-70th-anniversary-special-anime-film-on-ramayana-to-be-released/