Moreover, because of the nature of the animated film, because it is a unique combination of printed popular culture (as in drawings done for newspapers, books, and magazines) and the twentieth century’s later emphasis on more life-like visual media (such as film, television, and various form of photography) it is argued here that it is within the most constructed of all moving images of the female form – the heroine of the animated film – that the most telling aspects of Woman as the subject of Hollywood iconography and (in the case of the output of US animation studios) ideas of American womanhood are to be found. (Davis 2006, p. 3)

Figure 1 : J’aime les filles (Obom, 2016) © NFB, all rights reserved.

As a practitioner and film animation professor Laval University (BASA), it is essential for me to understand the marginal positioning of animated films and more particularly animated work created by women. The National Film Board of Canada’s[1] animated films are recognized all over the world,[2] earning the most prestigious honors.[3] But if their work is ignored by the general public, there is no doubt that it participates, as I will show in this article, to the diffusion of a different view, an alternative to mainstream media productions about female sexuality that is far from advertising, far from Betty Boop, Jessica Rabbit and Disney princesses.

Women’s inequality in the field of filmmaking and the aim of parity in Canadian film production are still current issues. In fact, following in the footsteps of the NFB, Société de Développement des Entreprises Culturelles (SODEC) and Telefilm Canada have recently introduced measures to encourage women’s access to film funding as directors, writers and producers. In May 2018, as part of the Cannes International Film Festival, 82 women walked up the steps of the Palais des Festivals to denounce inequalities in the field. These women represented the 82 female directors who had films at the prestigious competition and they were up against 1688 male directors. The Piano Lesson (Jane Campion, 1994) still remains the only film made by a woman to win the Palme d’Or.

As is well-known, recognition is an important factor for the promotion and archiving of films. As for the production of fiction feature films, only four women have been nominated for an Oscar since their debut.[4] And, in 2010, the first woman won the title as director: Katherine Bigelow for The Hurt Locker (2009).[5] As for the animated feature film category, out of the nine women[6] who were nominated, only three[7] won the Oscar for Best Animated Film, but they have always shared the title with male co-directors.

The history of Québec’s women animated film directors is yet to be written. I propose here that it is critical to look at animated cinema as an art and from a feminist perspective: animation made by women promotes a lively aesthetic on the fringes of commercial industry and productions. If feminist film studies have recently been interested in the work of female animators,[8] the history of Quebec cinema seems silent about their work. Without answering the reasons for this lack of interest, this observation motivates a generative literature with the objective of “looking at the absence of a historical awareness of the struggle of the pioneers” (Beaudet in Carrière, p. 219).

Figure 2 : La Basse-Cour (Michèle Cournoyer, 1992) © NFB, all rights reserved.

More specifically, this article explores Québec’s image-by-image cinema under an atypical, intimate and personal formal proposition – that of desire and sexuality through the female gaze in three works: Premiers Jours (Clorinda Warny, 1980), La Basse-Cour (Michèle Cournoyer, 1992) and J’aime les filles (Obom, aka Diane Obomsawin, 2016). I analyze these three films because they use female iconography to portray women’s sexuality from a woman’s point of view, based on the personal experiences of the filmmakers, while critiquing androcentric representations of women. That is to say, these are subversive in the representations of the female figure: it is not shaped under the masculine, white and heterosexual gaze. These three films propose a different approach to the negativity associated with women’s sexuality as usually represented in traditional live action cinema. Moreover, as animated cinema is a particular language, I am interested in its encounter with feminist thought. But first, it is essential to look at the contexts that favored the women’s accession as directors of animated films in Quebec.

Women’s accession to the field of animated cinema in Québec

In Femmes et cinéma québécois (Carrière, 1983), Louise Beaudet wrote the chapter A Breach in the Fief, the only article devoted to film animation. The author, who was the curator of animated film at the Cinémathèque Québécoise from 1973 to 1996, explores from the outset why the field of animation seems to have been more favorable to women, compared to documentary and fiction:

the equation animated cinema = children’s cinema and Dysney’s imagery conveyed by a family-type incarnation, certified safe with its kilometers of proper imagery, far from the adulterous sofas, ended up petrifying in the spirits. So what’s more “natural” than giving a woman a domain supposedly reserved for kids? (Beaudet in Carrière 1983, p. 214)

It seems that L’animation au féminin (Edera 1983) would be the first international study on female animators. It is in this text that we find the famous quote: “Man tells a story, woman tells her story” (1983, p.29). In his research, Bruno Edera proposes that the medium of animation is “the least misogynistic of the fields of the film and television sphere” (ibid). He does not go into detail about the causes or the findings of this favorable situation for women. Moreover, Edera’s perception of the nature of women is misogynistic – he argues,

Animation cinema is well suited to women because of its technical aspects, close to what is called “manual work.” One can think in particular of the embroidery which requires a lot of care and patience and can be exercised without taking into account the atmospheric conditions. […] The nature and goals of animation are also, to a certain extent, closer to certain feminine concerns – education, information – than masculine ones. (p. 30)

Yet, to speak of a feminine art is to combine and reduce the words of all women with ideas attributable to their anatomical destiny, Edera thus maintains the myth of the “female” film, a creative activity that would be inscribed in the biological specificity of women. In the essay “Pratique du pouvoir et idée de Nature (2): Le discours de la Nature” (1978), Coletter Guillaumin argues that in society, we find the construct of the “natural nature” of women and the “cultural nature” of men. Feminine nature is described by the dominant group as docile, patient, submissive, weak and without intelligence. Thus, women’s cinema is often associated with a light cinematographic art which is addressed exclusively to women. It is the trap of essentialism that unfolds; a phenomenon that barricades all women in the same set. As it is demonstrated in the founding text of feminist art history Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? (Nochlin 1971), artists of the same era often have more in common than those who are grouped by their genre.

In the field of cinema, it has been amply shown that the traditional representations of women are those of the “woman-object.” Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema (Mulvey, 1975) is a key text. For Mulvey, the stereotypical constructions of female characters in dominant cinema, shaped by the symbolic unconscious, are the vehicle of male fantasies projected on the screen. Since films generates figures and relations reproducing the ideologies of traditional gender relations, the viewer can only watch films with the “male gaze;” that is to say, he must wear the glasses of a heterosexual man to derive maximum pleasure: it is for him that the film is built. The cinema unconsciously reproduces the androcentric behaviour of society. According to Mulvey then, cinema is a voyeuristic activity in which the masculine gaze is active and the feminine passive. By identifying with the male protagonist, the viewer thus projects a dual erotic function on the female character. In the vast majority of American fiction films, the function of the heroine serves to generate and justify the actions of the male protagonist. Problematizing the formation of canons, as Griselda Pollock (1999) has done, is essential in feminist research:

Canons may be understood, therefore, as the retrospectively legitimating backbone of a cultural and political identity, a consolidated narrative of origin, conferring authority on the texts selected to naturalise this function. […] The canon signifies what academic institutions establish as the best, the most representative, and the most significant texts – or objects – in literature, art history or music. (Pollock 1999, p.3)

Artistic canons are synonymous with universal values, carried by dominant discourses, legitimizing the parameters and contours of what is valid. These are mythical constructions and women have been almost entirely excluded from these discourses made by the dominant androcentric society. Thus, some female filmmakers are engaged in a quest to promote an awareness among women of their oppression and domination. They want to build a “counter-hegemonic” discourse (Pollock 1999). Filmmakers use cinema to promote ideas of the feminist movements, such as women’s rights or gender equality, while criticizing the heteronormative system.

If feminine cinema is not necessarily feminist, feminist cinema is not necessarily feminine. The actions of women are not “natural” but conditioned by the social relations of sex. The evolution of feminine representations in Quebec’s cinema resonates with the socio-cultural transformations of La Belle Province, in concert with the feminist demands of the “second wave.”

I am often asked why women seem to have had more direct access to animated filmmaking rather than documentary and fiction. Certainly, the emancipation of women through education and the democratization of the medium have favoured a wider opening of animation to artists. But it is not trivial that image-by-image cinema allows filmmakers to occupy almost all the positions necessary for the completion of their works: scriptwriting, animation, production, photography and production. Perhaps this is one of the reasons why women have had access to this field – by working alone on their animated creations, they have been able to get out of the hegemonic and androcentric system governing the film production system in which they were mostly subjugated to men.

There is also the fact that image-by-image cinema is perhaps better adapted to the reality of some women, especially for those who have made the choice to be mothers. In my personal experience, I was able to make eight animated films between 2006 and 2018, while giving birth to my three daughters, because I could practice my art in the comfort of my home.[9] No matter what time, my desk was there, ready for me. I did not have any travel constraints. The length of my work period geared to the rhythm of my daughters’ life, housework and the demanding family obligations of a single mother. This is a factor that has favoured women’s access to animation films: the possibility of circumventing the physical constraints of film production Animation offers creative possibilities that can be executed entirely in the private space of the house. As denounced in A Room of One’s Own (Woolf 1929), the economic conditions of women’s lives greatly influence their chances of being able to create a body of work.

The frugality of the production’s means is a great quality of image-by-image cinema. The NFB’s McLarenian productions illustrate these creative possibilities with an economy of means. “It’s easy for anyone who has brushes and paint to make an animated film. It’s a possibility that brings animated filmmaking down to the level of home handy craft” (McLaren in Saint-Pierre 2006). These alternatives, less expensive and more accessible, certainly encourage artists to turn to animation and offer creative possibilities closer to crafts or DIY. The economic realities of women’s lives are often more difficult (wage disparity, poverty or financial dependence) and this precariousness probably influenced the choice of some female directors.

More than economic and family constraints, women’s access to frame-by-frame production also depends on their geographic location (Pilling 1992). Just like gender relations, cultural objects are also the product of society and it is essential to emphasize that the three films analyzed are produced by the NFB. The contribution of the NFB’s animation studio the fertile ground of Quebec’s animation is undeniable: we owe a lot to the state institution.[10]

The NFB is, in a way, a micro-society: financed by public funds, it evolves on the edge of the commercial industry. That is, it is not entirely subject to the laws of the market since it operates according to its own rules. It is governed by civil servants. In other words, since these state productions are carried out in parallel with the commercial markets, they are insubordinate to the pressures of profitability.

Figure 3 : Norman McLaren and Evelyn Lambart © NFB, all rights reserved.

After the Second World War, the vision of the Grierson’s propagandist effort was no longer a priority for the NFB and the animation department continued its artistic production where the originality of form and content was valued. Norman McLaren already produced experimental propagandist films supported by Grierson; especially V for Victory (Norman McLaren, 1941) and Five four Four (Norman McLaren, 1942). Evelyn Lambart, NFB’s first female animation director called it “derivative work [that] was absolutely hated [. …] We didn’t do any cel work at all, in fact we were highly contemptuous of Disney” (Pilling 1992, p. 31).

This search for innovation was influenced by the vision of cinematographic exploration. Motivated by the institutional desire to rethink the beacons of the Seventh Art, the NFB’s animated films are indeed popular with critics and film festivals: their innovations offer the public new cinematographic alternatives. The animation program produced films at low cost while simultaneously gaining a significant international influence. The NFB is an institution that is recognized around the world as greatly contributing to the development of animation as an art while promoting women’s access to filmmaking.

In fact, the NFB is a democratic and innovative government agency. The state institution constantly responds to the socio-political contexts of its time. In the early 1970s, positive discrimination measures were put in place for women to gain access to filmmaking. As a part of the program Société Nouvelle (Challenge for Change)[11] the project En tant que femmes (proposed by Anne Claire Poirier, Jeanne Morazain et Monique Larocque)[12] sees the day. From this positive discrimination initiative, six feature-length fiction and documentary films, addressing real issues of oppressions as experienced by women in Quebec were created.[13] This pioneering series reaches its audience and placed issues faced by women in private into the public eye. These issues included abortion, daycare, access to the labor market and marriage.[14]

Thus, the transformation of the cinematographic production field at the NFB in the early 1970s changed the professional activities of women who were mainly intended for assistantship or secretarial work. Women moved from manual activities to an intellectual work. This initiative marked a break in the production norms and encouraged the emergence of newcomers, new voices and new feminine perspectives on society.

This should perhaps be seen as a continuation of the institution’s propagandist initiatory aims, which currently extend into creating favourable conditions for the continued production of animated cinema from a feminist perspective. It is therefore in the very heart of state production that female directors have a certain political agency that allows them to express their voices as women. Female directors can thus propose an alternative representational strategies that differs from the “male gaze” denounced by Mulvey. With its history of positive discrimination measures, the NFB presents perhaps a situation for film production unique in the world for women animators. They have the opportunity to create an animated cinema founded by the state, but that allows the exploration of the boundaries between cinema and the arts while offering the chance to take a political stance, within the confines of an institutional feminist framework.[15]

Female agency in animated cinema

Figure 4 : Premiers Jours (Clorinda Warny, 1980) © NFB, all rights reserved.

If sexuality is culturally constructed within existing power relations, then the postulation of a normative sexuality that is “before,” “outside” or “beyond” power is a cultural impossibility and a politically impracticable dream, one that postpones the concrete and contemporary task of rethinking subversive possibilities for sexuality and identity within the terms of power itself. This critical task presumes, of course, that to operate within the matrix of power is not the same as to replicate uncritically relations of domination. It offers the possibility of a repetition of the law which is not its consolidation, but its displacement. (Butler, 2006, p. 106)

Instead of constraining the voice of women, the NFB (as a place of power) promotes women’s creative vitality through sanctionning modalities of expression in cinematographic representations. Filmmakers have access, through their works, to affirming feminist points of view that have a direct impact on society. As Betty Friedan already said in the early 1960s, these alternative possibilities of feminine representation by women make it possible to overcome the androcentric mentality that shapes images of women in art, advertising and the media.

As I demonstrate in the following analysis, animation allows us to explore women’s sexuality and desire in ways that are simply not possible in live action. Since the filmmaker must create her film world from scratch, animation “is clearly the cinematographic form closest to the imagination” (Denis 2017, p.8). Unlike live action, animated cinema does not usually strive to reproduce reality.

A dreamlike dimension can be associated with image-by-image cinema: fantasies, desires and metaphors. Since animated elements are not subject to the laws of physics or logic, the aesthetics of animated cinema reconfigures our relationship to and our perception of reality. Anthropomorphism defies the laws of nature and abstracts from reality. It is the whole relationship between the human and the object that is destabilized. Thus, the animated image offers the viewer a unique experience because in the world of animation, “there is absolutely no distinction between appearance and reality” (Beckman 2014, p.7). The abstractive possibilities of the cinematographic language are increased tenfold because everything is imaginary. Animation is a powerful tool able to create metaphors about society and the human condition.

By giving life to the drawings, the animator becomes in a way the actress who performs in front of the audience: this phenomenon is the exclusive prerogative of animation. By creating image by image, it is the intimate world of the animator that opens to the world offering the viewer a privileged dive into her imagination. It is not the real world that is portrayed in the animators’ films, but the relationships they have with the the real world. The animator is involved in the aesthetic experience. “In animation, there is a soul. Between the character and the animator, there is not only the effort to give him the movement. Something remains of the heat that accompanied the creation” (in Clarens 2000, p. 32). The filmmaker’s place as an artist is evidenced by the physical trace of her passage in the work: her gestures, her interpretations and reconstructions of the movement.

When the animator speaks, she allows us to see how she understands and critiques the world around her. “Each film reflects the unique vision and skills of a single artist, in concept and form, in style and substance” (Starr [1987] in Furniss 2009, p. 10). The agentive possibilities of female animators within the NFB are very real: with their films, they can propose social representations in reaction to the structure imposed by society. They animate the way in which they live their sexuality by taking the initiative to explore it freely, outside social dictates.

In this context, women animators have the capacity to act because they speak by making films; they have the power to act against the representation of stereotyped female sexuality in cinema by defeating the myths of the girl, the whore, the lesbian, etc. The animators are in a position of subject and not object. The first exploratory step at the NFB of female sexuality, Premiers Jours (1980), a posthumous film by Clorinda Warny, is part of a claimant position but not explicit.[16]

Premiers jours (Clorinda Warny, 1980)

Figure 5 : Clorinda Warny © NFB, all rights reserved.

To make a film like the one we working on, it is necessary to really feel it, to have it in the “belly.” This film is the link between nature and man. It is the four seasons of nature and, at the same time, the four seasons of the couple[…] (Warny in Champoux, 1997, p. 2)

From a feminist perspective, this animated film is a claimant since it allows Warny to speak about sexuality. Her position is not explicit because the representation of sexuality fits with the female archetype of the mother earth, shaped for the gaze of a conventional collective imagination. Heteronormative sexual representation, the driving force of the division of the sexes and the segregation of women in the private sphere, confines Warny’s critique to a traditional vision of sex between men and women. The essentialised version of the mother-nature woman leads to her ultimate biological destiny: that of childbirth.

The director, importantly, does not hyper-sexualize either the female protagonist or sexual intercourse. Warny renegotiates the androcentric look: a first step is thus made, especially if we compare the representation of Warny’s female character to Betty Boop[17] or Jessica Rabbit.[18]

In Premiers jours, a reversal of the stereotyped representation of gendered genres takes place. The female character is not created as the sexual object coveted by male desire but rather as her equal; she is in no way subordinate to her companion. In this sense, it is a positive point of view on the power of women (their agentivity) through their sexuality.

The great strength of Premiers Jours is […] to reconnect us with the drives and the raw energies, the rhythm of the seasons, the wind, the sea and the love. Outbursts and appeasement of passions and suffering, taming of life, so many themes that describe the threads of our hidden existence. (Carrière 1984, p.43)

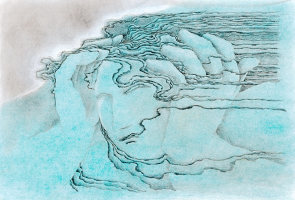

The complexity of eroticism is staged with continual metamorphoses of intertwined bodies. The different parts of anatomy merge into one another, unite and disintegrate with the rhythm of the seasons. The approach is poetic and the lines, sometimes abstract but fluid in motion, are hypnotic. A great ballet of pencil drawings that are continually changing, suggesting embracing faces, welded bodies, phallic symbols, metaphors of feminine curves and the life of the fetus. Caresses and arms unite, fire ignites behind passionate embraces, folds and crevices are alternately buttocks, thighs and breasts. The connection of the elements of nature with human bodies makes the red sun (which rises on the horizon, behind a mountain) turn into a nipple raised towards the sky. During a rotation of the mountains appear the naked bodies of the man and the woman.

Figure 6 : Premiers Jours (Clorinda Warny, 1980) © NFB, all rights reserved.

If the first seasons of the film offer a positive and united vision of the couple (from the thaw of spring to the heat of summer), the short film ends in winter. Thus comes the suggestion of painful emotions with the storm, wind, thunder and lightning. The passion of the couple is no more. An impression of distress, pain and isolation comes from the blue and cold colouring in conclusion. The protagonists no longer make love, they sit next to each other, in the sea, adrift. Must we see here the impossible cohabitation of a couple whose worn-out passion has immured them in silence and solitude? Maybe. And when the snow sets in, the humans are gone.

The colours of the film are essential part of the narrative: the colours change to support the evolution of the dramatic arc in which Warny, Gagnon and Gervais used “pastel, prints and Prismacolor pencils to give relief to the drawings [. …] The colours were animated, that is to say set in motion” (Gagnon 1980, p.8). The colour range sets precise temperatures and lights for each season which accentuates the emotions the audience is meant to feel. In 1981, the film won a Special Jury Prize at the Annecy International Animation Film Festival. But more than its narrative and aesthetic characteristics, without questioning the material qualities of the film, it is arguable that the “myth” of the artist (with her premature death at the age of 39) helped promote public interest in her work.[19]

Access to animated short films and issues around their distribution have always been problematic outside specialized circles. However, the NFB offers Petit Bonheur (Clorinda Warny 1972) and Premiers Jours for free online viewing.[20] Premiers Jours is an essential film; an entry into the personal universe of the director, a surrealist vision of her inner world with a touch of eroticism cleverly dosed that also leaves room for varied interpretations. Warny drives fresh representations of female desire in an androcentric heterosexual world.

La Basse-Cour (Michèle Cournoyer 1992)

Figure 7 & 8: Michèle Cournoyer and an image from he film La Basse-Cour (1992) © NFB, all rights reserved.

There is often a frank and earthy expression of sexuality which is a million miles away from the stereotyped cartoon sexiness […]. There has been a tendency for women to use animation as an intimate, confessional means of expression […] an extension of the clarification and projection of the inner world which may be what many women animators find so satisfying. (Ruth Lingford, SD)

After making several short films independently, La Basse-Cour is Michèle Cournoyer first’s work produced at the NFB.[21] This short film offers an extraordinary dive into the emotional life of her autrice: the illustration of the difficult relationship she has with her lover. It’s an illusion through an illusion. The action takes place in the animated imagination of Cournoyer. The subjectivity of the author is inherent to the film: she deploys her experience of suffering in a toxic love relationship that seems to be carried by a magnetic sexual attraction. Against her own logic, intoxicated by passion, the protagonist can not bring herself to ignore the appeal of the satisfaction of her sexual desires and this works to the detriment of her personal happiness.

Often, I put myself on the stage. I do what I call autofiction. When I play what I lived, the intensity comes back and prolongs these emotions. […] This is a way for me to completely root out the demons from my system. When the movie is over, I’m done with that story. […] This is a process comparable to grief. (Cournoyer in Roy, p. 34)

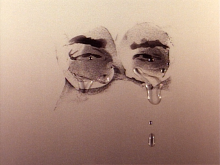

In the first sequence of the film, an egg is broken and then appears crying eyes of the animator. The symbol of the egg, the origin of the world, is split in two. This symbolizes the narrative arc that moves from rejection to acceptance, from the past to the future and from domination to empowerment. The egg, as an image of perfection and fragility, is broken. It is the end of a cycle, the promise of a return to life, a rebirth. A broken egg is no longer viable and the hen no longer needs to hatch it. This first sequence may express the director’s new look at her own pain as she voluntarily exposes herself to this undesirable situation. Her look offers an introspective vision of her broken love dream. It is an opening to the world, the sovereign consciousness of a passage from blindness to clairvoyance.

The film continues with the protagonist who takes a call from her lover in the night. As she holds the phone to her ear, it transforms into a man. Tiny, he whispers in her ear and strokes her hair. One feels all the impotence of the woman, unable to resist the call from her lover. This desire is confrontational and positions her in a situation of subjection. As she goes by taxi to her lover’s home, the car travels the entire distance on her naked body. Lying on her stomach, her eyes closed, she is motionless, as if nailed to the ground. “Drawing on my body, emotions come to the surface. […] When I executed the drawing, I was the taxi ride again. I could not see anything around me I was so eager to arrive. The rest did not exist anymore” (Cournoyer in Roy 2009, p. 35).

The woman’s face reappears inside the taxi wheel as it stops slowly. The protagonist morphs into a cardboard box, like those used to deliver chicken by a rotisserie chain. The woman is thus carried by a delivery man to her lover’s appartment. When the man opens the box, she is a beautiful hen adorned with feathers and the animator’s face. The director may have decided to self-represent with the chicken because this bird has sacrificial value in some religious ceremonies around the world.

Figure 9 and 10 : La Basse-Cour (Michèle Cournoyer, 1992) © NFB, all rights reserved.

The man first caresses the hen, who loves his caresses, in the manner of a master who cajoles his pet. When he takes the hen out of her box, she is half-human and half-animal. The man tries to catch the hen-woman but struggles to put his hands on her. She tries to escape her lover who wants to coax her by bringing her back to him, but she moves further away.

It is at this moment that the film changes completely and that the woman loses all sexual agentivity. From a woman who leaves in the night to satisfy her sexual impulses, she now finds herself in the situation of the victim. The man grabs her violently, against her will, and begins to pluck her feathers savagely. The hen-woman finds herself in a passive and masochistic position, alienated by her own sexual desire.

If the male spectator identifies with the lover (Mulvey 1975), he can live his fantasy of punishing this turbulent woman in a sadistic way to better possess her. The hen-woman, the object of his sexual frustration, who threatens him in his virility by her refusal to surrender herself to him is motionless, completely naked and lying on her back, defenseless on the table. The mutilated woman no longer has any power over her destiny. Having full control over the object of his sexual desire, the man takes the plucked hen in his hands and bites into her. The psychological violence inflicted on her hits the viewer.

Figure 11 : La Basse-Cour (Michèle Cournoyer, 1992) © NFB, all rights reserved.

The film concludes with the awakening of the woman, naked, next to her lover, deeply asleep. He’s snoring. She sits on the edge of the bed and she is cold. On the floor, next to her feet, lies a pile of white feathers. She is melancholic, disappointed and disillusioned. She feels lost, abandonned and she is suffering. Her expectations are not fulfilled, she does not find love: the crying at the beginning of the film makes sense now. The loss of self-esteem certainly follows.

The animation technique, which combines rotoscopy, black ink and white paint, gives the impression of an antique finish, as a direct access to the memories of the author. As a mirror of her personal experience, La Basse-Cour represents the lack of authority and agency of the protagonist and artist. It is an image of power relations between the sexes that expresses crudely male domination. This film that causes discomfort since it exposes everything: the sexual desires of the man are prioritized at the expense of the emotional needs and physical safety of the chicken. The woman is subordinate to her lover and used for her body.

J’aime les filles (Obom, 2016)

Figure 12: Obom © NFB, all rights reserved.

Awareness about the representational stereotyping of lesbians in cinema that inspired Obom to direct J’aime les filles. There are few strong and positive lesbian and queer female role models in the Seventh Art that queer women can identify with. Often, there is a cliché to lesbian protagonists in cinema; their fate is to commit suicide or sink into madness. By destroying lesbian women at the end of their stories, male filmmakers sanction the social prohibition of lesbianism. Explicit lesbian sexuality used to be extremely rare in cinema, unlike that of gay men who are represented in greater numbers. Thus, concerned with the problem of portraying, cinematically, relationships between two women in love in cinema, Obom grasps the possibility of raising awarness through new forms of lesbian reprensentation. She makes a film where the woman is a desiring subject excluding the masculine gaze; she constructs a feminine fantasy for a spectatorial experience not concerned with the desires of the heterosexual man. The film’s protagonists are agentive about the exploration of their desires for the same sex. In J’aime les filles, the author reappropriates the figure of the lesbian to make a political film, without being explicitly claimant, and that is the great strength of her work.

Figure 13: J’aime les filles (2016) © NFB, all rights reserved.

Obom speaks without aggression and denounces prejudices. By reversing the stereotypes associated with the popular icon of the lesbian, she addresses female homosexuality in a way that downplays the taboo. The way Obom choses to represent women, this diversion of a certain cartoon aesthetic more oriented towards children, is effective. By adding animal heads to the human bodies of her characters, she sets up the distance needed to master their image. Women are not fetishized, but reassuring and gentle. The elements are set up to create empathy for characters. Obom offers a new identificatory position for the spectators: the characters are strong heroines and not victims.

Animation, as a medium, transforms the perception of this serious themes around sexuality. They lose their ceremonial aspects because sexuality, especially here lesbian sexuality, is approached through this particular cinematographic language. It is a form of social and political protest that incorporates humour. Rather than stereotyping desirous relationships between women, it is the dynamic possibilities of animated characters that make the point. Basically, Obom takes us to the heart of the discovery of the love and desire between two human beings. The central message has a universal scope: all, heterosexual, homosexual or bisexual viewers will recognize themselves in these stories told with lightness, humour and frankness. This animation is the story of everyone who falls in love and who experiences a sexual desire for the first time. However, it differs critically from the universal heteronormative perspective.

Figure 14: J’aime les filles (2016) © NFB, all rights reserved.

For example, a young girl discovers, to her great surprise, that it is possible to kiss another girl. A protagonist experiences the wrath of her mother who refuses her sexual orientation, separates her from her beloved and sends her to a farm hoping that she will change. Obom is also self-portrays with great candor. She takes the stage by animating her own discovery of homosexuality and this happens in a dream. This mise en abyme demonstrates the mastery Obom has acheived in the art of storytelling: sensuality, sweetness, proximity and the warmth of love are reflected through her film.

Figure 15: J’aime les filles (2016) © NFB, all rights reserved.

This animation is touching because it is the personal look at an artist regarding her direct experiences alone and with her friends. Among the awards crowning the film (including the highly prestigious Grand Prix at theOttawa International Animation Festival), it’s the Prix du Jeune Public at the Festival International du Film pour Enfants de Montréal who deeply touched the director. For Obom, it is essential that her film be seen by young audiences. Even though much progress has been made for homosexual rights in Quebec, along with the more broad and general acceptance of sexualities outside the heteronormative system, Obom believes that there is still a feeling of repression, dejection and shame associated with lesbianism. Even today, many young people commit suicide after discovering their homosexuality because of social stigma associated with it. The characters in his film are young and still live with their parents. It is a positive message of hope with a happy ending that she offers.

With this film, the director is agentive. She intervenes intentionally to change things with the aim of informing and transforming preconceived ideas about homosexual desire. First a comic strip, J’aime les filles proposes a minority gaze, still taboo, of human relationships: that of romance and love between women.[22]

Figure 16: J’aime les filles (2016) © NFB, all rights reserved.

How could we promote animation films directed by women? It is by opening the borders, widening the university curriculum and diversifying the contents presented in the official institutions. These actions will create the conditions of possibility allowing us to move away from the canonical discourse in the field of the arts which relegates the animated cinema to the status of minor art, thus reducing its female directors to silence. By proposing an alternative to official discourses that challenges the normative dissemination of knowledge about Quebec animated cinema has been built, the work of the female animators will be documented, archived, widely viewed and recognized.

Reflecting on the everyday experience of women’s lives with the tools of animation is a unique opportunity to revisit history from a feminist perspective and to understand the realities and challenges of society. Quebec animation filmmakers themselves have written very little about their work and their history. It is necessary to speak about women’s perspective on animation and to explore the feminine imagination. It is essential to produce this kind of reflection in order to contribute to the recognition of the field of animated cinema and elevate its standing as legitimate film art in academic institutions.

I could not finish this article without recommending the unclassifiable Asparagus (Suzan Pitt, 1978) and The Carnival of the Animals (Michaela Pàvlàtova, 2006) who both propose an exploration of sexuality from a uniquely female point of view. These films are the manifestation of a cinematographic imagination in what the director has most intimate, that is to say the place of the expression of her sexuality.

This article was the subject of a communication at the University Paris Nanterre in the framework of the 8th International Congress of Feminist Research in La Francophonie for the symposium (Re) productions and subversions of the genre in the media of yesterday and today. Sex, body, powers and social media under the chairmanship of Professor Estelle Lebel.

This article was published in the original French in the fall 2019 issue of Nouvelles Vues under the title, Cinéma d’animation québécois et agentivité féminine; une exploration de la sexualité et du désir à travers trois œuvres d’animatrices produites à l’Office National du Film du Canada : http://nouvellesvues.org/cinema-danimation-quebecois-et-agentivite-feminine-une-exploration-de-la-sexualite-et-du-desir-a-travers-trois-oeuvres-danimatrices-produites-a-loffice-national-du-film-du/

References

BEAUDET, Louise. (1983) « Une brèche dans le fief». Dans Louise Carrière (dir), Femmes et cinéma québécois, p. 212-224. Montréal : Boréal Express.

BECKMAN, Karen. (2014). Animating film theory. Durham : Duke University Press. 359 p.

BUTLER, Judith. (2006). Trouble dans le genre. Paris. 283 p.

CARRIÈRE, Louise, (1983). Femmes et cinéma québécois. Montréal : Boréal Express. 282 p.

CARRIÈRE, Louise, (1984). « Et si on changeait la vie ? (animation ONF 1968-1984) ». Les dossiers de la cinémathèque. p.42-47.

CHAMPOUX, Lucie, Clorinda et Lina ont choisi le film d’animation. Photo-Journal, 19 mars 1977.

CLARENS, Bernard. (2000). André Martin : écrits sur l’animation 1. Paris : Dreamland éditeur. 271 p.

DAVIS, Amy M. (2006). Good Girls & Wicked Witches : Women in Disney’s Feature Animation. New Barnett : John Libbey Publishing Ltd. 274 p.

DENIS, Sébastien. (2017). Le cinéma d’animation : techniques, esthétiques, imaginaires (3e édition. Malakoff : Armand Collin. 317 p.

EDERA, Bruno. (1983). L’animation au féminin. La revue du cinéma, No. 389, p. 29- 42.

FRIEDAN, Betty. (1963). The Feminine Mystique. New York : W. W. Norton & Company. 562 p.

GAGNON, Lina. (1980) À propos de PREMIERS JOURS, ASIFA, Volume 8, Numéro 2, p. 8-9.

GUILLAUMIN, Colette. (1978). Pratique du pouvoir et idée de la Nature (2) : Le discours de la Nature. Questions Féministes, No.3 p. 5-28.

HEINICH, Nicole. (1991). La Gloire de Van Gogh : Essai d’anthropologie de l’admiration. Lonrai : Les Éditions de Minuit. 257 p.

HONESS ROE, Bella. (2013). Animated Documentary. London : Palgrave Macmillan. 173 p.

LINGFORD, Ruth. (SD) Women animators with a distinctive feminine and/or feminist perspective. Version en ligne de “BFI Screenonline”. Récupéré de <http://www.screenonline.org.uk/film/id/468226/index.html>. Consulté le 18 mai 2018.

NADEAU, Chantal. (1992). Are you talking to me? Les enjeux du women’s cinema pour un regard féministe. Cinémas, 2 (2-3), p. 171-191

MULVEY, Laura. [1975] (2009). visual and other pleasures (second edition). Londres : Palgrave Macmillan. 229 p.

NOCHLIN, Linda. [1971] (2009) Woman, Art, and Power and Other Essays. Colorado : Westview Press, 181 p.

OBOM. (2015). J’aime les filles. Montréal : L’Oie de Cravan.

PÉRUSSE, Denise. (1997). Le spectacle du « manque féminin » au cinéma : un leurre qui en cache un autre. Cinémas, 8 (1-2), p. 67-91

PILLING, Jayne. (1992) Women and Animation : A Compendium, Suffolk, St Edmundsbury Press Ltd, 1992, 144 p.

PILLING, Jayne. (2012) Animating the Unconscious : Desire, Sexuality, and Animation, Wallflower Press, London. 220 p.

POLLOCK, Griselda. (1999). Differencing the canon. Feminist Desire and the Writing of Art’s Histories. New York : Routledge. 345 p.

ROY, Julie. (2009). Le corps et l’inconscient comme éléments de création dans le cinéma d’ animation de Michèle Cournoyer. Université de Montréal, Faculté des études supérieures et postdoctorales, Montréal. Maîtrise en études cinématographiques.

STARR, Cecile. (2009) « Fine Art Animation. » Dans Maureen Furniss (dir). Animation – Art and Industry. P. 9-11. New Barnet : John Libbey Publishing Ltd. 240 p.

SAINT-PIERRE, Marie-Josée (producer and filmmaker). (2006). McLaren’s Negatices. [animated film ]. Canada : MJSTP Films.

THÉBAUD, Françoise. (2007) Écrire l’histoire des femmes et du genre. ENS Éditions, Lyon. 312 p.

WOOLF, Virginia. [1929] (1992). Une chambre à soi. Paris : Éditions Denoël, 171 p

Notes

[1] In order to lighten the text, the abbreviation NFB will be used.

[2] The men who created animated films in Canada also stood out. Back wins the Oscar twice with Crac! (Frédéric Back,1981) and L’homme qui plantait des arbres (Frédéric Back, 1987). McLaren wins the Oscar for the best animated short documentary with Neighbours (Norman McLaren, 1952) and the Palme d’Or at the Cannes International Film Festival for the best short film with Blinkity Blank (Norman McLaren, 1955).

[3] Animated shorts have garnered awards such as the Palme d’Or in Cannes with When the Day Breaks (Amanda Forbis and Wendy Tilby, 1999) the Golden Bear in Berlin for Black Soul (Martine Chartrand, 2001) or the Oscar with The Danish Poet (Torill Kove, 2007).

[4] Pasqualino (Lina Wertmüller, 1977), The Piano Lesson (Jane Campion, 1994), Lost in Translation (Sofia Coppola, 2004) and The Hurt Locker (Kathryn Bigelow, 2009).

[5] Strangely, in The Hurt Locker, there is no female character talking – the dialogues are fully interpreted by the male protagonists.

[6] The co-director of Persepolis (Marjane Satrapi, 2007), the director of Kung Fu Panda 2 (Jennifer Yuh Nelson, 2011), the co-director of How to train your Dragon 2 (Bonnie Arnold, 2015), the co-director de Frozen (Jennifer Lee, 2010), co-director of Brave (Brenda Chapman, 2012), co-director of Coco (Darla K. Anderson, 2017), co-director of Van Gogh’s Passion (Dorota Kobiela, 2017) and co-director Parvana, a childhood in Afghanistan (Nora Twomey, 2017).

[7] Jennifer Lee (2010), Brenda Chapman (2012) and Darla K. Anderson (2017).

[8] See especially the works of Jane Pilling, Bella Honess Roe as well as Amy M. Davis.

[9] McLaren’s Negatves (Marie-Josée Saint-Pierre, 2006), Passages (Marie-Josée Saint-Pierre, 2008), The Sapporo Project (Marie-Josée Saint-Pierre, 2010), Femelles (Marie-Josée Saint-Pierre, 2012), Jutra (Marie-Josée Saint-Pierre, 2014), Flocons (Marie-Josée Saint-Pierre, 2014), Oscar (Marie-Josée Saint-Pierre, 2016) and Your mother is a thief! (Marie-Josée Saint-Pierre, 2018).

[10] The geopolitical, socio-cultural and historical contexts of the NFB’s implementation are too complex to be exposed in this article.

[11] The problem addressed by the program Société Nouvelle (Challenge for Change) is triple: to allow the expression of minority cultures in Canada through cinema, to disseminate this minority knowledge among the general public and decision-making bodies, and finally to collect valuable information from minorities in order to better understand their realities, visions and their challenges.

[12] Since the program Société Nouvelle (Challenge for Change) puts the NFB’s audio-visual resources at the disposal of the Canadian population belonging to a minority culture, women working at the NFB (feeling aggrieved with not having access to filmmaking) seize the opportunity. They apply for funding for the project En tant que Femmes. Their objective is to make films about women’s experiences, made by women and, as far as possible, having only women working in all aspects of production.

[13] Themes and films made as part of the program En tant que femmes are: loss of identity through marriage and motherhood with Souris, tu m’inquiètes (Aimée Danis, 1973), state daycare in À qui appartient ce gage? (Matrhe Blackburn, Susan Huycke, Jeanne Morazain, Francine Saïa, et Clorinda Warny, 1973), the complex relationships that women have with men in J’me marie, j’me marie pas (Mireille Dansereau, 1973), the history of women and the labor market in Les filles du Roy (Anne Claire Poirier, 1974), feminine adolescence in Les filles, c’est pas pareil (Hélène Girard, 1974) and contraception and abortion in Le temps de l’avant (Anne Claire Poirier, 1975).

[14] Among the major demands of the “second wave” of the feminist movement in Quebec there is the decriminalization and access to abortion, access to contraception and state intervention to protect women from violence (physical and sexual) in the private space. The unifying motto of this period is: “The private is political! ”

[15] Moreover, the creative potential of animated cinema remains unlimited, new animation techniques are constantly invented.

[16] Clorinda Warny died on March 4, 1978, at the age of thirty-nine, from a heart attack. Her untimely death occurs during the production of the film Premiers Jours. Since all the animation had been completed, the french animation department decided to save the film and engage Lina Gagnon and Suzanne Gervais to complete the colouring.

[17] Betty Boop is the first female character to take the lead role in an American animated series (Fleischer Studios, 1930). Her representation is sexualized.

[18] Jessica Rabbit is in the film Who Wants to Frame Roger Rabbit? (Zemeckis, 1988). As a singer in a jazz cabaret, she is physically distorted by the stereotypes of female hyper-sexualisation.

[19] The phenomenon of the mythification of artists is addressed in, among others: Differencing the canon. Feminist Desire and the Writing of Art’s Histories (Griselda Pollock, 1999) and La Gloire de Van Gogh : Essai d’anthropologie de l’admiration. (Nathalie Heinich, 1991).

[20] Produced by Gaston Sarault, Petit Bonheur (1973) is a seven-minute color animation movie. It is the story of a young mother who walks her inconsolable baby in a stroller. She tries to calm him by all means, but to no avail. Anger and helplessness seize her. Then, children’s professionals, all male, come to give her advice. The toy seller believes that she should stimulate her child through play. The doctor believes the baby needs psychotherapy. As for the soldier, his solution is to train the baby with others to submit to orders. All men quarrel to know which of them offers the right solution. The baby is still screaming and is completely red. Then, he begins to urinate abundantly on all the male protagonists, which relieves him and he becomes perfectly happy again.

[21] L’homme et l’enfant (Michèle Cournoyer, 1969), Alfredo (Michèle Cournoyer, 1971), Spaghettata (Michèle Cournoyer et Jacques Drouin, 1976), La toccata (Michèle Cournoyer, 1977), Old Orchard Beach, P.Q. (1982) and Dolorosa (Michèle Cournoyer, 1988).

[22] OBOM. (2015). J’aime les filles. Montréal : L’Oie de Cravan.