There will be a time when people gaze at paintings, and ask why the objects remain rigid and stiff. They will demand action. – Winsor McCay (qtd. in Wells 1998).

Digital tools have brought about a “tectonic shift” throughout the world of art and design practice, redefining the economic viability and utility of previously prevailing techniques (Furniss 2009). Where creators might once have employed a breadth of tools and physical materials to create a work, now more so than ever, a single computer and a single piece of software may be used (Parks 2016). Due to this, the market has become so heavily saturated by computer rendered graphics and uncanny realism, causing artists and practitioners across all mediums to return to their roots through physical materials (Parks 2016).

For some, this is a welcomed and healthy backlash against the intangibility of the digital age (Furniss, 2009). Scholars such as Dr. Paul Hamilton argue how digital technology poses a threat to the role and development of drawing as a skill, as it makes it possible to produce images without the foundational skills traditionally needed (Hamilton, 2009; Roome, 2011). Others appear to be embracing the modern era: arguing that the digital has become an essential part of the creative process (Roome 2011). In marrying the two apparent extremes, these artists are attempting to make the digital seem more craft than computer.

This is not to suggest that “traditional technology will become redundant” – for it is the artist not the tool that makes the mark – but rather, it represents a paradigm shift in how we view this new technology as a creative resource (Roome 2011). By utilising existing frameworks of knowledge and these newly available avenues of exploration, the pencil and the mouse have become almost interchangeable (Hamilton 2009).

It is with this in mind that this paper sets out to explore the hybridity of old and new methods within my own field of animation. As an approach I find especially appealing, particular attention will be paid to the unique work of direct under camera animators, in order to understand how their practice and aesthetics may be mimicked through and translated for a digital workflow. By combining analogue methods with digital platforms, it is hoped that not only will animators have a greater array of stylistic options while working with the computer, but this may also allow some physicality, permanence, and lasting resonance to a medium that is intangible, and in essence, formless.

I begin my discussion first by looking at the distinctive methodological approaches and visual appeal of direct under camera animation, before reflectively exploring those elements with regards to digital processes.

Approach and Appeal

There is a rich history of direct under camera animation. The works have a tendency to be transformative, poetic, rhythmic, and dramatic; due in part to the medium itself, and in part to its ability to channel the personality of the artist at work (Gehman and Reinke 2005; Korakidou and Charitos 2006). While the most widely known form of traditional animation utilises prepared graphics and painted cels, direct under camera animation is one of creative spontaneity, individuality, and experimentalism (Russett 1976). It is made up entirely of liquid lines and fluid frames (Parks 2016).

Typically, the work is created by manipulating some form of fluid medium directly under a rostrum camera, most commonly on a sheet of under-lit glass, though other surfaces may be used (Russett 1976). These mediums are chosen for their liquidity, or the ability to be reworked overtime, such as: oil and gouache paint, sand and salt, clay, and charcoal (Parks, 2016). As these materials are invariably difficult to control beneath the camera, the animator must act as both a painter and a sculptor in order to create each image (Parks 2016). They then must photograph, and subsequently destroy the image in order to create the next (Parks 2016). It is an intrinsically vicious circle of creation and destruction. As Parks notes, it is a way of working that requires “confidence, intuition, and stamina.” (Parks 2016). It is a process which truly tests the artist’s abilities as an animator, their ability to adapt and to work with any mistakes that may have been made (Parks 2016).

While many may imagine this a toe-curling endeavour, it is an allure in itself to many brave animators, such as Caroline Leaf, who notes: “To me it seems more alive than conventional cel animation, both to make it and to see it, for it is all made in one stage and the films show my hesitations and miscalculations and flickers with finger-prints and quick strokes.” (Russett, 1976).

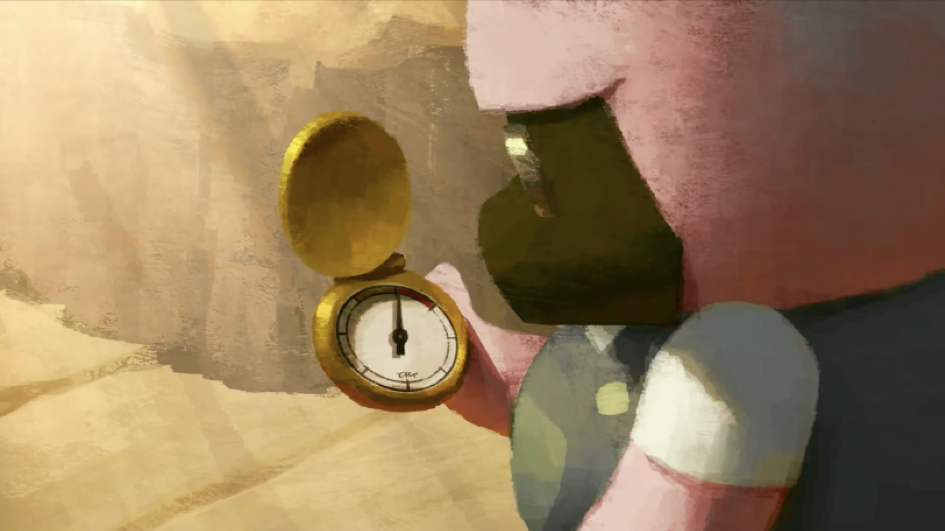

Of course, not only is there an appeal in working this way, but the finished product can be astoundingly beautiful. For example, one of the most notable animators using the direct under camera animation method is the Russian filmmaker, Alexander Petrov. With his adaptations of Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea (1999), and Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Dream of a Ridiculous Man (1992), among various other impressive works, he shows his strengths as a craftsman, painter, and animator (Wiedemann 2007).

Working with slow-drying pastel oil paints on a multi-layered sheet glass canvas with no more than his finger-tips as his instruments of choice, he manipulates the medium into images that hark back to the work of the romanticists, and the impressionists (Wiedemann, 2007). It is as if the paintings themselves had come to life. Yet, this draws us to question: what makes these works so visually pleasing?

Figure 1: Still from Alexander Petrov’s The Old Man and the Sea (1999).

It must be recognised that, in the case of many films within the realm of art and animation, “the novelty of the technique trumps all”, regardless of the narrative being told (Parks 2016). Viewers are often “fascinated by the artistic process”, and any work that takes an experimental approach to a technique “holds infinitely more wonder” than the prevailing methods known and accepted by the public (Parks, 2016).

In the case of direct under camera animation, that wonder is primarily built on the shoulders of three giants: the mark, metamorphosis, and mortality. Each of these are apparent throughout almost every work of direct under camera animation, regardless of whether paint or charcoal is being employed, and so it is important to understand exactly what they are.

The Mark

Defined as a trace left on a surface, the mark exists in many forms, whether it be a scratch or smudge (Wayne and Peters, 2003). It can boast variations of width, weight, tone, speed, and gesture in the brushstroke, or can convey shape and texture through the thumbprint. The mark can be static but violent, gestural and soft. It is the single most important aspect of any visual art for that utilises a material to create imagery. For example, in Vincent Van Gogh’s The Starry Night the clouds and trees, though static, appear to swirl and spin based purely on his application of the brushstrokes.

Figure 2: Still from Joanna Quinn’s Girls’ Night Out (1987), showing her distinctive line-quality.

In animation, the mark is important for two distinct qualities. Not only can it be used to emphasise the flow, movement and direction of a particular image or sequence, as in The Starry Night, but can also show the presence of the animator (Wells, 1998). For example, in Joanna Quinn’s Girls’ Night Out (1987), she explores her enjoyment of mark-making through the movements of her characters and objects (Wells, 1998). With her use of “fluid and organic pencil lines” to emphasise her main character’s effort of movement due to her comic appeal, they are a telling sign of Quinn, her renowned hand-drawn style, and the energy she endows on her creations (Wells, 1998). This creates a vital connection between the artist and the audience, often missing from other forms of animation created through a large-scale production pipeline. It allows both the artist to exhibit their personal traits and passions, while also telling the audience that this piece was made by a person, not a machine – as many appear to believe with so-called ‘push of a button’ 3D rendered imagery (Wells, 1998; Parks, 2016).

Metamorphosis

Though metamorphosis is not unique to direct under camera animation, it is arguably more visible (Wells, 1998). As a medium is manipulated and recorded, each image appears to merge and melt into the next (Van Laerhoven, Di Fiore, Van Haevre, and Van Reeth, 2011). This creates a very fluid and organic process of continual transformation. Particularly when clay and powders are in use, there is little distinction between the background and foreground, for they are generally created and modified simultaneously on a single plane of existence. Figures may move “not by walking, but by being smudged” into the next state, the required location, or to be reformed and melt into their surroundings (Van Laerhoven, Di Fiore, Van Haevre, and Van Reeth, 2011).

This is a prominent visual aesthetic of Joan C. Gratz’s Mona Lisa Descending a Staircase (1992). Working with a diluted clay and mineral oil mixture, Gratz’ film is described as an “art history course stuff inside a kaleidoscope”, as she recreates famous works of art in an ever-transforming sequence (Kipp, 2009). The clay is treated and acts as painted brushstrokes in the style of the artist being mimicked. In an experimental montage of metamorphosis, Mona Lisa unravels into various images of haunting self-portraits and landscapes. It is as if the animation process consists of waves, where the image exists in a constant rise and fall of movement before being washed away.

Figure 3: Still from Joan C. Gratz’s Mona Lisa Descending a Staircase (1992), showing an example of metamorphosis, as one painting transforms into another.

Similarly, in The Ballad of Holland Island House (2015) by Lyn Tomlinson, clay painting is used along with a musical ballad accompaniment. The narrative is told from the point of view of an old house, speaking of “its origin, its life, and its eventual decline”, as it sinks to the bottom of the sea (Behind the Scenes 2015). By methodically applying and adjusting small pieces of clay on a flat surface, Tomlinson is able to carry the story through images which appear to mould and meld into one another; be it the building, the family eating a meal together – clearly inspired by Van Gogh’s The Potato Eaters – or the wings of pelicans as they come to nest on the collapsing roof (Parks 2016).

Figure 4: Stills from Lyn Tomlinson’s Behind the Scenes: The Ballad of Holland Island House (2015) comparing the clay film still with Van Gogh’s The Potato Eaters.

Another fantastic example of this metamorphosis is in the work of Alexandra Korejwo, who, unlike Gratz and Tomlinson, works with dyed salt on glass (Korejwo 1996). This is employed much in the same way as Leaf’s sand, but with the added benefit of colour.

Usually in tandem with a piece of classical music she has chosen, there is an almost perfect synchronicity between the rhythm heard in the audio, and seen on the screen (Korejwo, 1996). Her work is fundamentally abstract and poetic, often based around dance choreography and music as a visual “synthesis of the dynamics of movement and sound” (Spicer 2015). She approaches her work as a performance, noting “my body speaks the same language, which is sometimes called dance, ballet or pantomime […] all the time I am looking for the point of meeting between poetry, movement, music and painting.” (Korejwo 1996). This is clear in her short film Carmen Habanera (1995), based on Bizet’s opera. The screen shows a static, grainy, red. It begins to flicker and dance with hints of yellow and white, folding like that of a cloth. Building with the music, the folds transform into the reclining figure of a beautiful woman in a red dress, before she rises and begins to dance with a graceful seduction. Like glistening atoms, the salt contains and creates all that exists in Korejwo’s work (Bendazzi 2016). Everything has an uncertain edge, and an unsteady and soft existence, which fluctuates as the music guides its movements. Between forms, objects and figures, the film holds the same resonance and beauty “as the fluidity of movement, the grace, the perfect balance of great ballet dancers” (Beaudet 1987). The transitions from one image to another is much less obvious than in the films of Gratz and Tomlinson. This is due not only to the speed and smoothness of its occurrence, but equally to the natural control Korejwo seems to have over the salt: its aqueous behaviour and textural nuances.

Figure 5: Still from Alexandra Korejwo’s Carmen Habanera (1995), showing the textural and fluid nature of the salt in a dramatic transformation.

Mortality

While creating her film Eine Kleine Nachtmusik about the life of Mozart, the camera used by Korejwo malfunctioned, destroying any recording of her work (Korejwo 1996). Under other circumstances, through other methods of animation, this would be seen as no more than a mere setback; but for Korejwo, in using a process often performed in a single sitting, it meant the loss of an entire film (Korejwo 1996). This inherent risk of loss illustrates the fragile and temporal nature of direct under camera animation. Each image is entropic. It exists only for the duration of its creation, meeting destruction upon completion. Only then can a new image be created.

This philosophy of impermanence can only really be understood by the animator during the process, for the persistence of vision allows the viewer not to see a sequence of images, but instead, the illusion of movement (Wells 1998). Yet, the methodological and thematic aesthetics of mortality distinct to direct under camera animation allows the viewer some understanding of the process, like breadcrumbs of knowledge.

Figure 6: Still from Petra Freeman’s Jumping Joan (1996), featuring “trails”.

For example, Petra Freeman makes clear use of the ghosting – or “leaving trails” – technique in her short film, Jumping Joan (1996), based loosely on the haunting nursery rhyme of the same name (Parks 2016). Utilising oil paints on a hard plaster surface, there is a visible “disturbance in the paint behind the character”, while creates a trail of secondary motion (Parks 2016). This gives an illuminative and ethereal quality to the imagery, which fits comfortably with the theme of isolation, as the character leaps between a mystical imagination, and a stark reality.

Figure 7: A haunting still from William Kentridge’s Felix in Exile (1994) with the distinctive residual marks of previous frames prominent to his work.

Similarly, this technique is employed by the artist and filmmaker, William Kentridge, due to the nature of his method. Often narratively and cinematographically reminiscent of Soviet-era animation films – which subverted image and language to allow meaning to bypass a strict and brutal censorship – Kentridge’s work is often thought of as mordant, theatrical, and overtly political (Kitson 2005; Furniss 2009; Cumming 2013). Working primarily in front of the camera on oversized sheets of paper, and using sticks of charcoal and pastels, he creates large-scale drawings (Manchester 2000). Suiting his dislike of the permanent line, these are images “capable of indefinite modifications,” from which he smudges out and adjusts where necessary (Parks, 2016). For his work, Felix in Exile (1994), he created and modified forty drawings (Manchester 2000). It features “African bodies with bleeding wounds” as they are slowly covered by flickering sheets of newsprint lifted by the wind, and shown to gradually “melt into the landscape” (Manchester 2000). Made shortly prior to the first general election of South Africa, it is a film with a strong political voice, carrying symbolic layers of memory through narrative and technique, as it questions “the way in which the people who had died on the journey to this new dispensation would be remembered” (Manchester 2000).

Though often focusing on the violent and troubling images of apartheid, there is an almost paradoxically peaceful tension in Kentridge’s work. Moments of action and inaction are performed with a soft, flickering consistency that can only be described as pleasing. With each new erasure and adjustment made in his drawings, there is a visible residue of smudged charcoal and fingerprints left from one frame to the next. This could be seen not only as a history of his mark-making – the ghost of himself implicit to the work – but as a perfect visualisation of decay and the persistence of memory (Hosea 2010; Parks 2016). For a moment in time, these images have been entrapped on a single sheet of paper: an incident recorded with meaning and conviction, both in the memory and the marks of the creator.

As I have shown, there is a distinct methodological and visual appeal in direct under camera animation. Having noted on the qualities of the mark, metamorphosis, and mortality, the tendency of this form of animation to be transformative, poetic, rhythmic and dramatic can be easily understood, solidifying Leaf’s statement of it seeming more “alive” (Gehman and Reinke 2005). With this language or tool set developed by direct under camera animators, in the following section, I will question how the traditional practice may be incorporated into a digital animation workflow, as well as some of the difficulties that may arise.

Combining Approaches

Working digitally can be advantageous for the artist and animator. Not only can it remove some of the inherent difficulties found in many processes, allowing the artist the freedom to explore without risk, but it contains a tool set that exceeds the capabilities of the physical (Parks 2016). Where the artist might once have used scissors and glue-sticks to create a collage, images can be cut, pasted, reversed, and manipulated indefinitely without ever affecting the original piece. It is a realm open to infinite possibilities.

Yet, this comes with its own hazards. It is easy to over-analyse and over-refine: removing the accidentals and elements of spontaneity that can make a work aesthetically pleasing, mechanising a very naturalistic process (Parks 2016). The artist must instead set and accept the limitations of the process they are using, attempting to work digitally as one would traditionally. Of course, this is not to suggest that virtual pencil, for example, should only be used in the same way as its physical counterpart. Instead, the artist should recognise its capabilities in order to be mindful of the marks they are making.

Figure 8: Still from the digitally hand-painted short film, The Dam Keeper (2014).

This recognition is apparent in Tonko House’s The Dam Keeper (2014), where it is clear that they made full use of the technological capabilities of their workflow, yet limited the visual aesthetics to one that resembles a mixture of pastels and watercolours. Similarly, the artist John Roome too shows an understanding of this in the extreme. His work, Journey into the Ineffable (2009) is particularly interesting as a perspective on the relationship between analogue and digital craftsmanship. Rather than using traditional methods as a starting point, he works conversely, beginning first with the digital (Roome, 2011). Working with no more than a mouse and Microsoft Paint, the most primitive of painting software, he sketches out images stylistically reminiscent of William Kentridge’s work (Roome, 2011). He appears to revel in the limitations of the software – showing that art is dependent on the artist, not the tool. Rejecting the perfect line-work that typically defines the computer as a medium of realism, his images allow for pixilation, expressing curved lines in a broken and low-fidelity, chicken-scratch geometry (Roome 2011).

Figure 9: Still from the projected animation element of Journey into the Ineffable (2009).

These images are then laboriously cut into wooden panels, which allows him to “slow down” the digital, following precisely the pixelated marks (Roome 2011). In doing so, his sculpting of the medium produces work that, though tangibly real, appears virtual. As digital art is in effect a “medium-less” process and therefore has a uniquely ambivalent nature, he suggests: “drawing with new technology need not be limited to the imitation of ‘manual technologies’.” (Roome 2011).

Though this sits in direct opposition to a digitising of direct under camera methods and aesthetics, it serves as a clear example of effectively merging the two approaches. Of course, the digital is not unknown to direct under camera animators. Many contemporary artists within the field make use of it in their workflow for conventional tasks, such as compositing and colour adjustment (Parks 2016). Yet, it may be considered virgin soil overall as a place in which direct under camera animation is created (Parks 2016).

Looking reflectively at my own process, my digital pencil-case is not unlike its physical counterpart: comprised of various brushes, erasers, and smudging tools. The marks are made with the same consistency as they would be working traditionally, but applied through a glass-screen graphics tablet monitor and a pressure sensitive stylus. Therefore, there is invariably little difference between the digital and the physical in my approach. Yet, due to its “promise of multiple revisions”, the digital is often used as a tool of rehearsal; a place in which to explore ideas and styles, before committing the work to permanence (Parks 2016). As a result of this, I have been experimenting with direct under camera animation digitally, while merely flirting with it traditionally.

Unfortunately, for the moment, a purely digital workflow for direct under camera animation is no more than a pipe-dream, as the alternatives are at best clunky. Naturally, there are various advantages in working digitally, such as: the ability to save, revise, and edit a work; to cut, paste, and manipulate elements within an image; to use layers (elements of an image can reside on different planes); onion-skin layers when animating (the frames before and after the current frame are shown as if through tracing paper); and the timeline, which allows an animator to watch and check their progress in real-time. An artist can also experiment with different materials, unreservedly dropping spots of paint on the virtual canvas, knowing nothing is being wasted. These tools allow the speed of production to increase, though the act of drawing or painting may be as time consuming as the traditional method. Unfortunately, however, no software is currently available to the public that has been designed with the intention of creating digital direct under camera animation. Therefore, these advantages come at the cost of working around the technological constraints that may not be deemed intuitive.

For example, the saying ‘the animator starts with nothing and builds everything’ is far more pronounced for the digital animator, for they are even without the natural textures and frictions produced with a pencil on paper. The digital world is a place where nothing truly exists, and so elements as simple as the textural nuances of a material must be imported. Thankfully, programs such as Photoshop contain a vast array of simulated materials which have been developed to act in a similar way as the real material would. Unfortunately, however, these do not contain the realistic dimensions and consistencies of mediums such as paint, sand, and clay, as found in direct under camera animation (Parks, 2016). The difficulty, then, is in finding the correct tool preset that can produce the desired mark, and be applied intuitively.

Figure 10: Still from the first of my 10×10 (2017) films, showing a digital application of ghosting.

In my own work for 10×10 (2017) – an annual event during which participants have ten days to create ten films – I made full use of the aesthetics of direct under camera animation. Having already discovered and modified a brush setting to create charcoal-like marks, I created a soft (low-opacity) eraser that produced a mixture of textures, including that of the thumbprint. By erasing, smudging, and modifying the work in the preceding image, copied to a new frame, I was easily able to replicate the residual build-up of marks, metamorphosis and ghosting, as discussed in the previous chapter. I would then move back through the animation, adding in elements of spontaneity, such as accidentals and scratches.

Similarly, in order to mimic the mark produced by a paint-on-glass animator, such as Petrov, I utilised brush presets that produced more opaque, hard-edged marks along with the smudge and liquify tool as manipulators. These added new dimensions to my work, which viewers found fascinating; not only as a visual aesthetic, but also to discover that the images they were seeing were not made with physical materials.

In essence, the difficulty is not in the mimicry and translation of the process and visual appeal, but rather in overcoming the limitations of the technology used. Though the technology can be considered efficient enough to produce the desired outcome, there are elements which need to be further investigated to make this a more proficient and economic process.

Thankfully, I am not the first to consider examining the digital world as a viable avenue for direct under camera animation. In the research of Van Laerhoven, Di Fiore, Van Haevre and Van Reeth, they designed and manufactured a screen prototype for digital direct under camera animation. By utilising a tactile multi-touch surface, an artist is able to use their fingers and brushes of various sizes to manipulate on-screen materials (Van Laerhovenet al 2011). These simulate the “complex behaviour of different paint media” in real-time, including that of gouache, watercolour, impasto, and pastel (Van Laerhoven et al 2011). Not only could this resolve the complaints formerly mentioned regarding the limitations of the available software, but by allowing different tools to interact with the screen, it would put an end to our subjection to pen-only stylus designs. In short, by creating software and hardware solutions, digital direct under camera animation may be made with the same intuition of method as in the traditional method.

Conclusion

As previously stated, digital tools have brought about a “tectonic shift” throughout the world of art and design (Furniss 2009). Not only are artists of all mediums are returning to their roots through physical materials in a process of exploration, but are also attempting to re-evaluate and redevelop previously defined methods through new media approaches; marrying the traditional with the digital (Parks 2016). It is with this in mind that this paper has set out to study direct under camera animation as an expressive and artistic form of filmmaking. By detailing the methodological approaches and visual appeal of this form of animation through engagement with various examples, three elements were shown to be distinctive qualities.

Firstly, the mark was explored as a technical and symbolic representation of the artist and their connection with the audience. Secondly, metamorphosis was presented as an important visual aesthetic, where one image may blend into the next. Lastly, elements of mortality were discussed, speaking both of the philosophy of impermanence as a quality inherent in direct under camera animation, as well as the “visual disturbance” and creation of secondary motion through ghosting (Parks, 2016).

This was followed by a brief discussion of blending the physical analogue and the intangible digital by looking at the work of Tonko House and John Roome. Here, it was established that an artist must set limitations when working in a digitally limitless world, such as understanding the physical capabilities of a traditional medium in order to guide the use of its digital counterpart; and conversely: how the digital may be used to inform traditional approaches.

Finally, through elements of reflectivity – using examples of my own practice – I succinctly explained how the approaches and aesthetics of direct under camera animation may be mimicked on a digital platform, and how the difficulties of current technology have a tendency to limit the artist and their capabilities when attempting to work digitally.

It may be argued that, though the pencil and the mouse have become almost interchangeable in the world of art and animation, for the direct under camera animator, much more exploration and development is needed. The digital world has come with a host of advantages beyond the physical capabilities of traditional mediums, and holds many new avenues of exploration. Yet, even as a place to experiment with and rehearse ideas, it is not yet capable of the same tactile and intuitive nature found in traditional practices. Instead, however, of attempting to develop a perfect digital representation of a traditional craft, artists should blend the hand-made with the computer generated in order to further develop both approaches simultaneously, as reliant partners of expression.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my supervisor Pasquale Iannone, Jared Taylor, Alan Mason, and Nichola Dobson for their help and advice in producing this text. I would also like to thank my friends and family for their patience, support, and understanding. Finally, I would like to extend my appreciation to Michael Havelin and Abigail Lamb, who supported my writing process through multiple in-depth discussions and far too many multiple cups of coffee.

Gary Wilson is a Scottish animator and visual development artist, interested in digitally-painted and ethnographic approaches to the animated landscape. He graduated with a Master of Fine Art in Animation from Edinburgh College of Art in 2016, has since continued to develop his voice as a filmmaker in the interim to PhD studies. www.gstwilson.com

References

Arnheim, R. (1954). Art and Visual Perception. California.

Bacher, H. (2007). Dream Worlds: Production Design for Animation. London and New York.

Barthes, R. (1997). Image Music Text. London.

Beaudet, L. (1987) cited: Fine Art Animation. [online]. Transcanfilm. Available at: http://transcanfilm.com/xenos/FAA.html [Accessed 02/12/2017].

Bendazzi, G. (2016). Animation: A World History: Volume III: Contemporary Times. UK.

Choldenko, A. (1991). The Illusion of Life: Essays on Animation. Sydney.

Cumming, L. (2013). A Universal Archive: William Kentridge as Printmaker – Review. [online] The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2013/aug/25/william-kentridge-printmaker-review [Accessed 02/12/2017].

Dütching, H. (2000). Wassily Kandinsky 1866-1944 A Revolution in Painting. London.

Enstice, W., Peters, M. (2011). Drawing: Space, Form, and Expression. Pearson.

Feild, R. D. (1944). The Art of Walt Disney. London and Glasgow.

Furniss, M. (2016). Animation: The Global History. London.

—. (1998). Art in Motion: Animation Aesthetics. Sydney.

—. (2009). Animation – Art and Industry. London.

Gehman, C., Reinke, S. (2005). The Sharpest Point: Animation at the End of Cinema. Toronto.

Hamilton, P. (2009). Drawing with Printmaking in a Digital Age. [online] TRACEY. Available at: http://www.lboro.ac.uk/microsites/sota/tracey/journal/dat/images/paul_hamilton.pdf [Accessed 02/12/2017]

Hosea, B. (2010). Drawing Animation. [online] Academia. Available at: http://www.academia.edu/12872534/Drawing_Animation [Accessed 02/12/2017]

Kipp, R. (2009). Mona Lisa Descending a Staircase. [online] Pop Matters. Available at: https://www.popmatters.com/the-best-metal-of-2017-2513310213.html [Accessed 02/12/2017].

Kitson, C. (2005). Yuri Norstein and Tale of Tales An Animator’s Journey. Indiana.

Korakidou, V., Charitos, D. (2006). Creating and Perceiving Abstract Animation. [online] Available at: http://www2.media.uoa.gr/~charitos/papers/other/KOC2006.pdf [Accessed 02/12/2017].

Korejwo, A. (1996). My Small Animation World [online] AWN. Available at: https://www.awn.com/mag/issue1.2/articles1.2/korejwo1.2.html [Accessed 02/12/2017]

Jesoinowski, J. E. (1987). Thinking in Pictures. California.

Manchester, E. (2000). William Kentridge Felix in Exile 1994. [online] Tate. Available at: http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/kentridge-felix-in-exile-t07479 [Accessed 02/12/2017].

Marion, J. S., Crowder, J. W. (2013). Visual Research: A Concise Introduction to Thinking Visually. London.

Parks, C. F. (2016). Fluid Frames: Experimental Animation with Sand, Clay, Paint and Pixels. London and New York.

Russet, R., Starr, C. (1976). Experimental Animation: Origins of a New Art. New York.

Roome, J. (2011). Digital Drawing and the Creative Process: In Response to Dr. Paul Hamilton, Drawing with printmaking technology [online] TRACEY. Available at: http://www.lboro.ac.uk/microsites/sota/tracey/journal/dat/images/John-Roome1.pdf [Accessed: 02/12/17].

Roome, J. (2011). Drawing in a Digital World: A self-critical analysis of the creative output of John Roome. [online] TRACEY. Available at: http://www.lboro.ac.uk/microsites/sota/tracey/journal/dat/images/John-Roome2.pdf [Accessed: 02/12/17].

Schön, D. A. (1983). The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. London and New York.

Solomon, C. (ed). (1987). The Art of the Animated Image: An Anthology. Los Angeles.

Van Laerhoven, T., Di Fiore, F., Van Haevre, W., Van Reeth, F. (2011). Paint-on-Glass Animation: The Fellowship of Digital Paint and Artisanal Control. [online] HAL. Available at: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00629936/document {Accessed 02/12/2017].

Wells, P. (1998). Understanding Animation. London.

Wells, P. & Moore, S. (2006). The Fundamentals of Animation. London and New York.

Wiedemann, J. (ed). (2007). Animation Now!. London.

Filmography

The Street. (1976). [film] Caroline Leaf.

Girls’ Night Out. (1987). [film] Joanna Quinn.

Mona Lisa Descending a Staircase. (1992). [film] Joan C. Gratz.

The Dream of a Ridiculous Man. (1992). [film] Alexander Petrov.

Jumping Joan. (1994). [film] Petra Freeman.

Felix in Exile (1994). [film] William Kentridge.

Carmen Habanera. (1995). [film] Alexandra Korejwo.

The Old Man and the Sea. (1999). [film] Alexander Petrov.

Journey into the Ineffable (2009). [film/exhibition] John Roome.

The Dam Keeper. (2014). [film]. Tonko House.

The Ballad of Holland Island House. (2015). [film] Lyn Tomlinson.

Behind the Scenes: The Ballad of Holland Island House. (2015). [film] Lyn Tomlinson.

10x10x17 1 (2017). [film] Gary Wilson.

© Gary Wilson